Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Occasionally, works of intellectual originality arise from the ferment of popular science writing. One such is David Deutsch's The Beginning of Infinity (Allen Lane, £25), which goes against the pessimistic grain of the times in suggesting that the scientific project begun in the 17th century has limitless possibilities and that the problems pressing on us now are all eminently soluble.

Bold in a more subtle, understated way than Deutsch is Jonah Lehrer's Proust was a Neuroscientist (Canongate, £16.99), a series of free-standing essays on artists and the scientific implications of their work. Lehrer's ability to write well about science, literature, visual art and music is a rare gift.

Jared Diamond has reclaimed a subject notorious for its shabby patched elbows with his radical geographising of history. His colleague at the University of California, Laurence C Smith, has now written the essential backgrounder for the coming era in which temperate civilisation moves north into the previous frozen tundra and boreal forest: The New North (Profile, £20). Smith marshals his material brilliantly and he has lived his vision, travelling in the region.

As we watch David Attenborough at the poles, it is a shock to be brought back to the reality that faced Scott in the Antarctic in 1912. That Scott's photographic record of what was a research expedition, not merely a trophy hunt, has been "lost" for 100 years is hard to credit. But here it is, in stark black and white, in David M Wilson's The Lost Photographs of Captain Scott (Little, Brown, £30).

Angela Saini's Geek Nation (Hodder & Stoughton, £20) is revealing reportage on India's scientific and technological renaissance. She shows how the Indian space programme was inspired by Arthur C Clarke, how fixing the millennium bug kickstarted the Indian IT revolution, and how relentless cramming to get into India's technical institutes is producing not always über-geeks but drones.

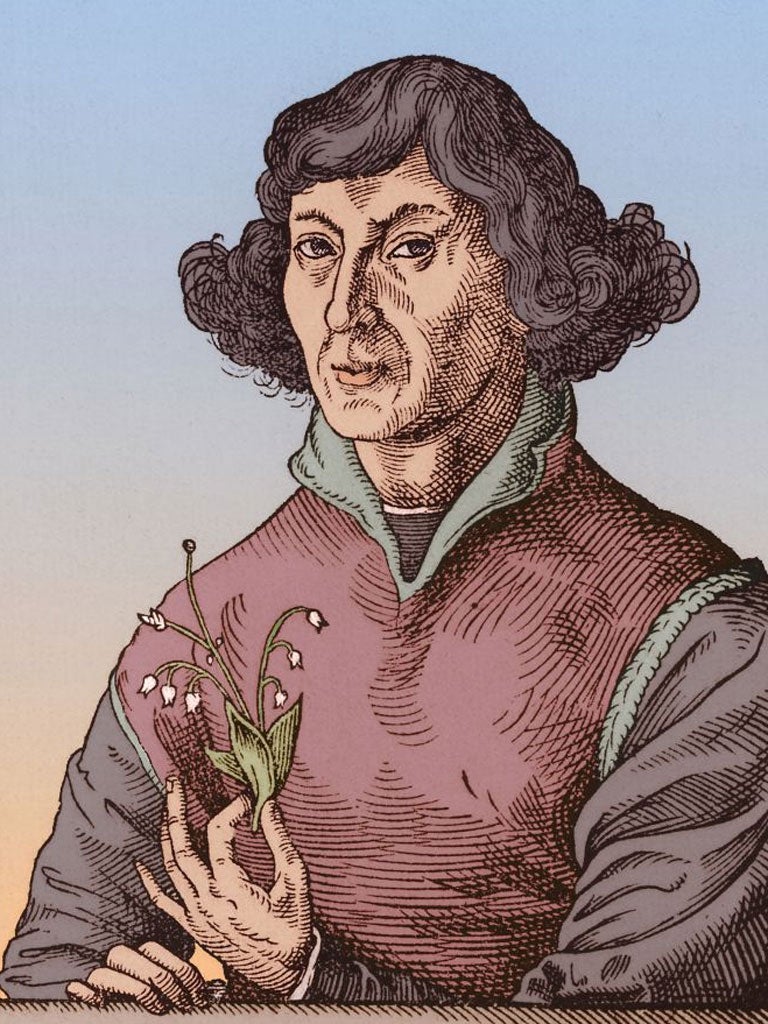

Perhaps it was inevitable that Longitude author Dava Sobel would turn to Copernicus: from the man who told us how far round the world we'd gone to the man who told us the earth revolves around the sun. In A More Perfect Heaven (Bloomsbury, £14.99), she adds a new twist in the form of a play, in the middle of the narrative, centred on Copernicus's meeting with Rheticus - the man who persuaded him to publish his theory that changed the world forever.

The study of human evolution is burgeoning, thanks partly to the new technique of sequencing ancient DNA. Two books bring us up to date. John Reader's sumptuously illustrated Missing Links (OUP, £25) focuses on the great fossil hunters and their discoveries. Chris Stringer's The Origin of Our Species (Allen Lane, £20) is the most thorough review of all the new techniques that are piecing together our true story at last.

Tim Radford's The Address Book (Fourth Estate, £16.99) traces the deep roots of geology and human evolution. He shows how the past is still more present than we could ever guess.

The book that will generate most discussion this year is Steven Pinker's The Better Angels of Our Nature (Allen Lane, £30). His explanations for the apparent paradox of how brutality and even genocide in the modern world coexist with a trend towards diminished violence are entirely convincing.

Philip Ball is the most polymathic science writer of our time. In Unnatural: The Heretical Idea of Making People (Bodley Head, £20) he casts a judicious eye on Craig Venter's claims to have "synthesized life"; the existing technology of IVF; the realistic prospects of stem cell therapy; and the possibility of genetically modified humans.

Richard Dawkins's The Magic of Reality (Bantam, £20) is an illustrated Book of Knowledge for younger readers, but with the added charisma of the master. Richard Mabey's The Perfumier and the Stinkhorn (Profile, £9.99) is a slender volume of talks from Radio 3, but a big-hearted book. Mabey describes himself as a "literary hunter gatherer" and he has carved out a very personal territory, somewhere between science, art and a romantic immersion in nature.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments