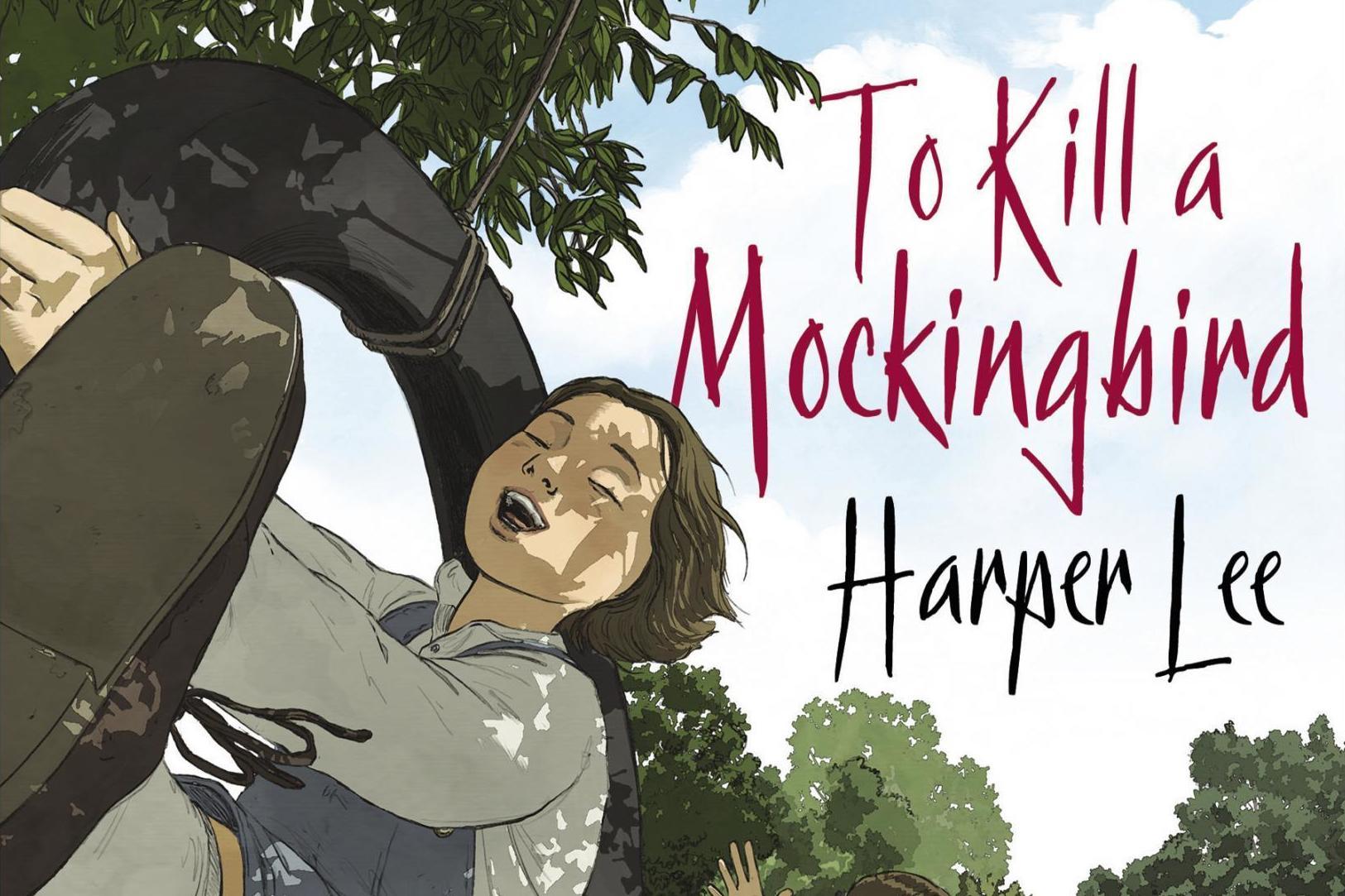

The rise of graphic novels, from Sabrina to To Kill a Mockingbird

‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ is now being released in graphic novel form, the latest sign of a growing appreciation for an art form once derided by critics. Martin Chilton talks to artist and writer Fred Fordham, who admits to having ‘thought about little else for a good year and a half’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The popularity of graphic novels is soaring and 2018 could turn out to be a key year for the genre. Sales of Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina rocketed this summer when it became the first graphic novel to be included on the Man Booker Prize longlist in the award’s 50-year history. A previous jury once dismissed this format as mere “comic books”.

Six decades after it was published, Harper Lee’s seminal novel To Kill a Mockingbird was voted the UK’s most-loved book, according to a World Book Night survey. Its continued popularity was shown this month, when a six-month PBS poll of more than four million American readers voted Lee’s classic as their favourite novel of all time. Now, it is being released in graphic novel form.

Drnaso’s book – about murder, truth, the internet and the crazy “fake news” cycle around the story of a missing woman – is vibrantly contemporary. The daunting challenge that faced artist and writer Fred Fordham was creating a modern and accurate illustrated version of a novel that has sold more than 40 million copies since its publication in 1960.

“I was not trying to re-invent Harper Lee’s novel,” Fordham says. “I was trying to do a faithful adaptation in a new medium. I have taken it very seriously and thought about little else for a good year and a half.”

The proposal for a new “special visual edition” of Lee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel came from the estate of Harper Lee. The project fits in with plans by Tonja Carter, Lee’s attorney and executor, to grow the author’s hometown of Monroeville, Alabama, into a major tourist destination for a new age.

Carter liked Fordham’s previous work. His first graphic novel, Nightfall, was published in 2013 in France – where around 5,000 graphic novels are published every year – and four years later he was chosen to illustrate Philip Pullman’s The Adventures of John Blake: The Mystery of the Ghost Ship.

After accepting the commission, 33-year-old Londoner Fordham went to America to soak in the atmosphere of the Deep South. “I had not been to America before, so I flew to New York and then on to Alabama for 10 days. That was two sides of a fairly wide coin. Monroeville is where Lee grew up, the place on which she based the novel. It is much more of an autobiographical novel than I realised, even down to the position of the houses. Although her former home is now a shop that sells ice creams, the famous courthouse survives and has been turned into a museum. The people working there have an encyclopaedic knowledge of the town and they shared their insights generously.”

The preparation Fordham undertook, allied to his training as a fine artist, meant he was able to bring a captivating realism to his illustrations, drawn with economy and effect. “I took pictures and did sketches of old frame houses, which are similar to how they were in Lee’s time,” says Fordham. “I knew the foliage and landscapes would be similar, although I had the ill-informed idea that southern Alabama would be quite arid. It was very green and lush, in fact.”

The locations feel real and you can also detect some of his previous training as a traditional portrait painter and muralist in the striking illustrations of minor characters such as Miss Maudie and Aunt Alexandra.

As well as finding the appropriate art style, Fordham had to adapt 100,000 words from the original prose into a long-form visual medium. “I read through the novel again several times and then I story-boarded the whole thing in quite a lot of detail,” says Fordham.

In many ways, Lee’s fiction writing is suited to the sequences of the comic book form and her sharp and impactful dialogue is perfect for the copious dialogue balloons. At the all-female Huntingdon College in Montgomery, the young Lee was known for her “salty language” and her knowledge of the sort of conversations natural to small town folk from the south was impeccable. “The people are not particularly sophisticated, naturally,” Lee said in 1964. “They’re not worldly wise in any way. But they tell you a story whenever they see you. We’re oral types – we talk.”

To open his version, Fordham reproduces (verbatim) the first 152 words of Lee’s novel before going straight into dialogue bubbles. “Lee had a free-flowing style and she jumps around spatially and temporally, and with illustrations that can be quite confusing,” says Fordham. “So there were a few occasions – such as the extended family history at the start of the novel – when I moved around description to avoid it being confusing, or I edited down parts where I thought a theme, such as learning to walk in other people’s shoes, had already been explored in depth. On the whole, though, because of the amount of beautiful dialogue, it was technically quite straightforward. It is not like trying to adapt Ulysses or Proust, although people have turned those into graphic novels.”

True, there have also been graphic novel versions of Shakespeare, Dickens, Bronte, Melville and Kafka – and even a Marvel Comics adaptation of Pride and Prejudice that is faithful to Austen’s original – but Lee’s depiction of racial discrimination continues to arouse controversy. The racial slur “nigger” appears about 50 times in the book. In 2017, a school district in Biloxi, Mississippi, banned the book from eighth grade classes over concerns that the language “makes people uncomfortable”. Former US secretary of education Arne Duncan, a Barack Obama appointment, re-tweeted a plea from a teacher in Chicago seeking crowdfunding help to purchase copies of the books for his school. “I want to make students think about issues that are relevant and worthwhile,” the teacher said.

The Lee estate and publishers William Heinemann address the issue of the use of the racial insult in a postscript note in Fordham’s book arguing that “the inclusion of the word – its dehumanising power and the ease with which it was used – is central to understanding the themes of the novel”.

“Technically it would have been difficult to do a version without using the word,” says Fordham, who has a degree from Sussex University in Politics and Philosophy. “There is a whole sequence where Atticus chastises Scout for using the word. The word is essential to the court scene. In the end, this is a semi-autobiographical account of life in rural Alabama during Jim Crow. It is an excruciating word that rightly has a gut-wrenching effect, but it was how people spoke. Harper Lee is an intellectually honest person and she was trying to give a real, visceral account of the gruesome side of life in 1930s Alabama. Do you want to sanitise the past, or say this is how it was and we should not forget how appalling it was?”

The scenes of violence in his book have a Marvel-like feel – with the words ‘WHACK’, ‘THUMP’, ‘WHAP’ and ‘SMACK’ presented in big bold capital letters – and reading Fordham’s book is an experience akin to watching a movie, especially his powerful presentation of the dramatic court battle. Fordham says he was careful not to be influenced by the 1962 Oscar-winning film adaptation of Lee’s novel, which starred Gregory Peck as the hero lawyer Atticus Finch.

“I didn’t want to be swayed so watched the film only after I had done the adaptation,” says Fordham. “It’s a wonderful film, but it is more of an Atticus story. The book is more a Scout story. My version is an adaptation of the novel, not the film. I understand why the film is beloved. Lee was so enthusiastic about Gregory Peck and I heard a lovely story about them. In one scene he had been emoting as much as possible while she was watching from the sides in tears. He was feeling really chuffed with himself and went up and said, ‘I’m pleased you were moved by it, I hope we’re doing a good job’. She just replied, ‘Oh, not that. You have a pot belly, just like my daddy’.”

Lee said the reason she liked the screen version was because “respect permeated everyone who had anything to do with the film”. Respect permeates Fordham’s book, not just in his admiration for her storytelling skills but also for the form of the graphic novel itself. The term, incidentally, was coined by American writer and publisher Richard Kyle in 1964, when he suggested calling comic books “graphic stories”. He disliked the more arcane term “illustrories”, which was in vogue at the time.

Fordham’s love of graphic novels goes back to his days as teenager, when he became interested in bande dessinée (the drawn comic strips of the 1930s, such as Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin) and the world of the graphic novel. He was particularly inspired by Marjane Satrapi’s graphic autobiography Persepolis, which depicts her upbringing in Iran during the Islamic Revolution.

He gained wider attention working as an illustrator for The Phoenix comic. “Fred Fordham came along when he was a young man with brilliant talent,” says publisher David Fickling. “He did some work on The Phoenix and then did a beautiful comic strip called ‘The Rocket of Rawangadalli’ with Ben Sharpe. Then we got him to do the John Blake novel with Philip Pullman and that really put him on the map, because it sold well here and in America, in Europe and the Far East. It was brilliant strip mastery and, from that job, he got the gig for To Kill a Mockingbird.

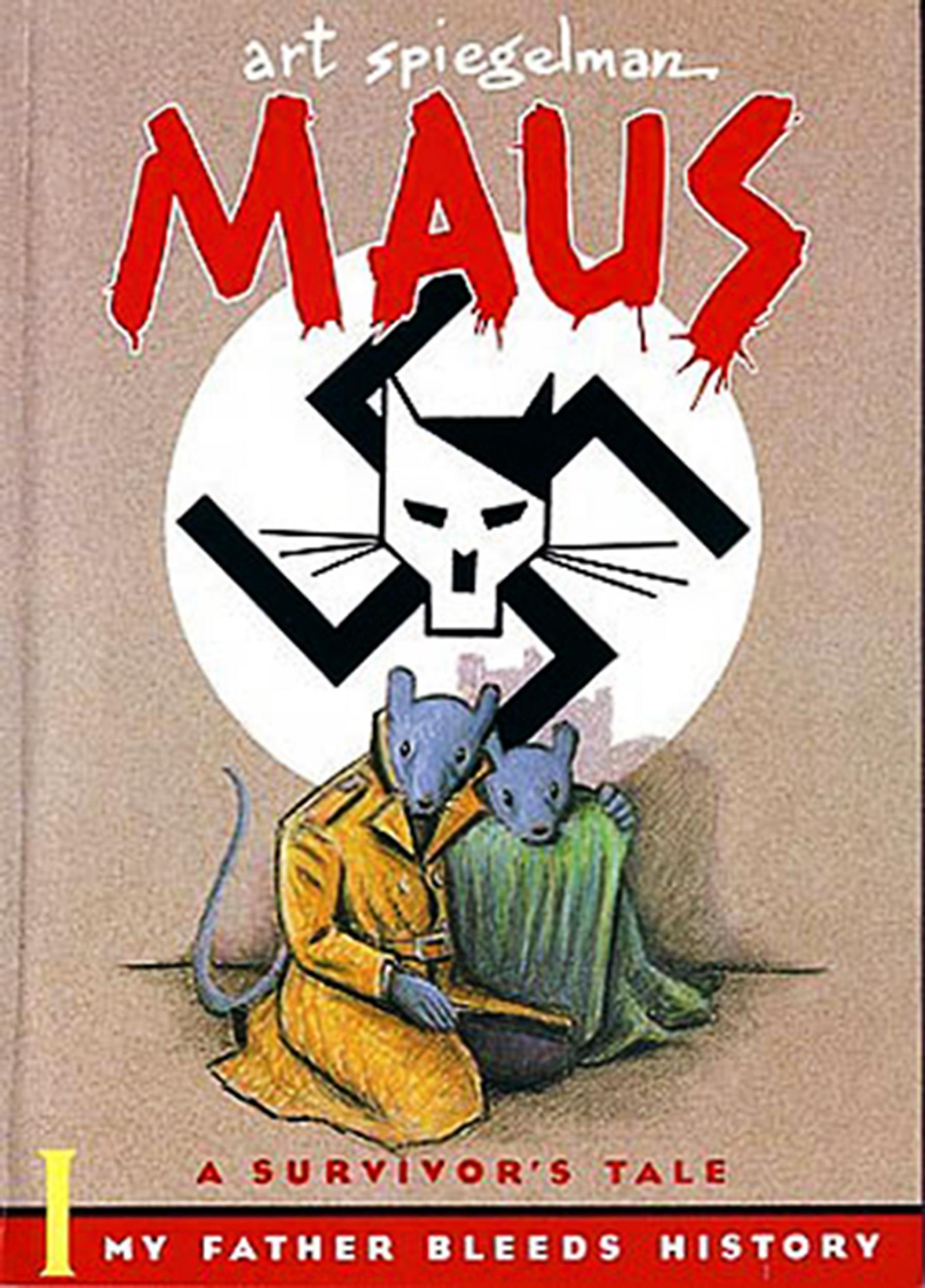

Graphic fiction is at a high point commercially and critically. “The Man Booker recognition for Sabrina will do something for the intellectual credibility of the graphic novel,” says Fordham. The nomination marked perhaps the most significant moment for the genre since Art Spiegelman’s Maus won a special Pulitzer Prize in 1992. That re-telling of his father’s experience in a concentration camp, using mice to represent Jewish prisoners and cats as Nazi guards, is a masterpiece.

There is a UK tradition of storytelling illustrations for Fordham to call upon. “In the 1960s and 1970s there was a huge market for comics and made up a lot of the hidden reading that was going on then,” says Fickling, who has published dozens of graphic novels. “There were about 40 weekly comics in that era and a rather snooty tendency to look down on them means they didn’t get the credit they deserved for promoting reading. I think comics will come back and be massive in the future. Comic readers are ideal for graphic novels, because they devour every single word in the boxes. They suck as much story out of it as they possibly can.

Fordham says he hopes that in the UK and USA “graphic novels are on the cusp of becoming an accepted media, as they are in France and Japan”. Harper Lee’s estate is certainly aiming to promote the novel, still purchased by more than a million people a year, as “reborn for a new age”.

Why does Fordham believe there is still this appetite for a story about life in 1930s Alabama?

“Lee wrote such a subtle portrayal of childhood, with fascinating young characters like Scout, Jem and Dill. It has that strange aspect of youngsters coming of age and learning about responsibility at the same time as recognising the prejudices and hypocrisies that you are expected to adopt as a grown-up,” says Fordham.

“As well as the grand themes, Lee has such vivid, universally recognisable characters, such as the town gossip, the troubled family down the road, the stoical father figure. People from anywhere and anytime can relate to these people from rural Alabama. I always thought To Kill a Mockingbird was primarily a courtroom drama and a book about prejudice drama, but it is the more general things about growing up and empathy that are universal.”

To Kill a Mockingbird, adapted and illustrated by Fred Fordham, is published by William Heinemann on Tuesday 30 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments