Richard Mason: The author explains why his career took a nose dive after penning a best-selling debut novel

Snapped up in his first year at Oxford by a publisher waving a fat advance, Richard Mason was catapulted into the big time. But only with the publication of his third novel has he shaken off his demons

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

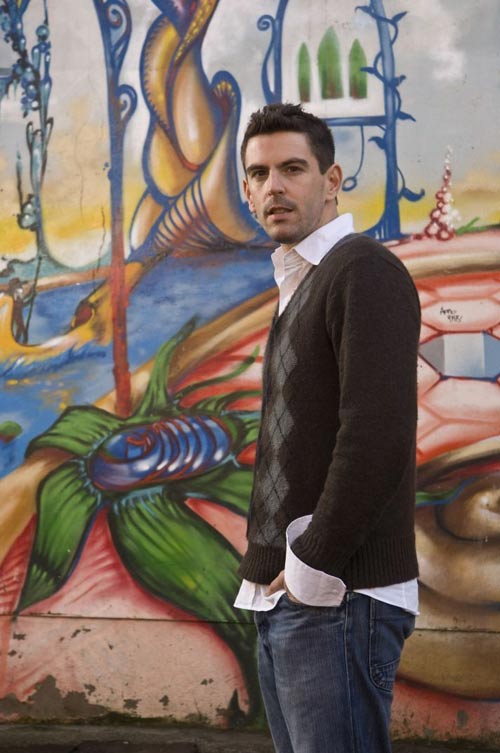

Your support makes all the difference.Richard Mason has advice for struggling novelists: be careful what you wish for, because it may drive you mad. It is advice based on bitter experience. Looking handsome and relaxed over breakfast at the Groucho, he is now 30 and a long way from the fresh-faced, eager-to-please author of The Drowning People I met over 10 years ago at one of the more upmarket book parties. His debut had just been snapped up for a stellar advance amid much publicity, making him the first of a brat pack of Oxbridge writers that included Zadie Smith and Hari Kunzru.

But while his Penguin stablemates were reasonably mature twentysomethings able to manage the hype created by their fat advances, Mason, 18 years old and in his first year at Oxford, seemed uncomfortable with the expectation the hype placed on him. "The whole experience left me thinking about that Aristotelian injunction, 'Be careful what you ask the gods lest they grant it you'," he says now.

As a teenager, Mason had asked the gods for quite a lot. They must have been listening. "All those idle daydreams I used to have at the back of my German GCSE class: living in Paris, writing a novel, seeing my name on a poster and winning a prize – every single thing happened," he says, sounding shocked. But rather than turning him into an over-confident monster, his luck left him racked with self-doubt. By the time he started Us, his second novel, he had placed himself under so much pressure that his confidence broke down and he seriously considered jacking it all in to become a lawyer.

His polite English public school exterior masks a much sharper, resilient and deeply compassionate person. A South African, he is the son of dissidents persecuted under the apartheid regime. Out of what I suspect is sheer bloody-mindedness he gave writing one more try, and has now published The Lighted Rooms with a new publisher.

"I needed to rediscover the kind of joy that used to make me wake up at four in the morning when I was 17 and make me write a short story. That is what I wanted to get back and The Lighted Rooms gave me that." He is beaming, and I am reminded how earnest he seemed when I first met him. I soon discover why he felt so uneasy back then.

The Lighted Rooms marks Mason's return to his native South Africa. Its focus is British atrocities in the Boer War. Like The Drowning People, it features an ageing protagonist, this time the delightfully dotty Joan McAllister, whose journey into Alzheimer's is accompanied by winged piano legs and terrifying visions of her own past and that of the nursing home she has been shunted into by her guilt-ridden daughter, Eloise. Slipping between a Boer War concentration camp and present-day London, the book is a thoughtful and at times hilarious challenge to assumptions about ageing, family and history, and draws an angry parallel between US action in Iraq and British action in the Transvaal.

"I wanted to make an analogy to what is currently happening in Iraq," Mason explains. Comparisons between Iraq and Korea or Vietnam are misguided, he believes. "The real analogy is South Africa in 1900. Back then you had the world's major superpower invading a resource-rich sovereign nation in the name of democracy, but with a very complex agenda that actually doesn't have very much to do with democracy," Mason explains. "They easily win the war, but find that they can't subdue a civilian population passionately opposed to occupation. Then, because they have the eyes of the world on them and everyone secretly wants them to fail, the superpower resorts to worse and worse civil rights abuses in order to stamp victory on a conquered people."

The British oppression included concentration camps, a legacy to history many Brits would rather ignore. A witness statement by Joan's grandmother, Gertruida, an inmate in one of the camps, reveals the horrific conditions in which the Afrikaners were kept. Her account is based on historical records, which explains Mason's anger at attempts to downplay similarities between the camps and those set up by the Nazis 30 years later. The camps were overcrowded, haunted by starvation, disease, desperation and death; Mason believes they poisoned the following century for South Africa.

His eyes are bright with passion as he talks about South Africa. The Lighted Rooms has fired his imagination, and, he says, his next books will be part of a loose series about characters related to one another through his homeland. The move away from England, in his imagination at least, is a rebellion against assumptions created by his Etonian accent. During a tour of Canada for The Drowning People he read an article that described him as an "all-round super-Brit". "I am definitely not all-round super anything and also I am not a Brit," he says with faux indignation. He doesn't even live in England; he's based in Glasgow with his partner Benjamin, whom he married when civil partnerships were legalised. "I went to an expensive English school because the South African government confiscated all my parents' money because they were dissidents and only let them spend it on their child's education." Slipping from Bloomsbury to Bloemfontein in one sentence, he adds: "I can talk like this. I probably should, then I would get a better write up in the left-wing press." He is laughing. Mason may talk of things he feels angry, hurt or incensed by, but he does not take himself too seriously. Perhaps it stems from his time at Eton; he has the outsider's ability to defuse anything about himself that may seem threatening or unlikeable.

His privileged education explains why he used money from The Drowning People to set up the Kay Mason Foundation in memory of his sister, who committed suicide in 1986. The foundation pays for gifted South African children from poor backgrounds to attend the country's top private schools. KMF is why Mason nearly collapsed under the pressure of his second novel. "I went to South Africa with money for about 25 kids and interviewed about 400 and got it down to 30," he explains. "They all started school in January 2003 and of course the Iraq War started in March and then the stock market crashed." In its wake so did the rand, and the KMF was left with a 30 per cent shortfall in its budget.

Mason responded to the crisis by placing himself under intolerable pressure to rewrite his second novel so that it would push all the buttons for his US publishers. "My American publishers were the ones with the money, so I decided I had to please them, which I would never have done otherwise. But if you promise an education to a child in a shack, you have to provide it." For a moment I catch a glimpse of the intense 20-year-old I met years ago. He understates the pressure he placed himself under: his then US publisher was very commercial, and Mason is a literary writer. Rewriting Us to suit a commercial market tore the soul out of the book and the heart out of Mason. He couldn't do it. "I began to think that the students we were supporting, who were 12 when they started school, were going to be middle-aged before I finished the fucking thing."

He is laughing as he recalls the experience, but in reality he was a nervous wreck, prone to bursting into tears in the street and on the verge of suicide. It was only then, supported by Benjamin, that he had courage to follow his muse rather than the market. "In the end I thought, actually I know I will calm down from this and in 10 years' time, if I have thrown it all away, I will be resentful," he says.

He gazes thoughtfully across the empty restaurant, as if in a daydream. Then he smiles, and says with the joy of someone who has finally accepted the gifts the gods have given him: "You should never be resentful, it is the worst possible emotion and makes life a real prison."

The extract

The Lighted Rooms, By Richard Mason (Weidenfeld £12.99)

'...I applied to the camp doctor but was told I must wait three days before I might see him. When at last my turn came I was told simply to go away, for "Did I not know all children under the age of five must die?" The word he used to me was "frek", which in Afrikaans refers to the death of animals, not of human beings... Johan was received into God's merciful care on 29 April, 1901...'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments