Poetry round-up: This season's collections ask 'who am I and where do I belong?'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This season's poetry collections are overwhelmingly concerned with place and identity. Three major volumes dealing with the question of Ireland dominate, threatening to overshadow English regionalism, Liz Berry's challenging topic in Black Country (Chatto & Windus, £10).

No such difficulty inhibits Ten: the New Wave (Bloodaxe, £9.95) a sampler of work by black minority ethnic poets that includes some of the best new verse to be found anywhere. Its contributors have all emerged from the Complete Works mentoring programme but there's no sense of this being apprentice work. Ably edited by Karen McCarthy Woolf, the anthology leads with Warsan Shire, whose excoriating bodily imagery and street and song rhythms combine with a heady clarity. It ends with Mona Arshi's poised and haunted work. Better-known contributors include Kayo Chingonyi, Jay Bernard and Sarah Howe, whose beautiful verse is crammed with thought, detail and story.

Fellow debutant Berry seems, excitingly, to be several poets in one. Narratives of urban childhood, chock-full of commuters, boys on bikes, and leering lorry-drivers, are expected of today's young poets, as is experiment with local dialect. Yet look closely and Black Country's gender-bending, once-upon-a-time narrators subvert this convention. Berry specialises in the fabulous: a pregnancy is and is not a "Grasshopper Warbler", while she herself "became a bird", "The air feathered/ as I knelt/ by my open window for the charm." This whimsical energy lifts her book out of the usual.

A Woman without a Country (Carcanet, £9.95) continues senior Irish emigrée Eavan Boland's examination of Irish women's identity. The title sequence portrays her grandmother as a woman "married in a poor country". Although it asserts "she was not Ireland" the symbolism of a double oppression seems, as often in Boland, to make that conflation. At times this revisiting of characteristic territory seems almost dutiful, yet the book includes some very fine writing. In "Advice to an Imagist", "salt" is a "word that comes/ to the edge of meaning/ and enters it". The movement of experience is both uncanny and real: "Light slips down from the Dublin hills"; meanwhile, "What will we do with the loneliness of the mythical?"

In The Whole and Rain-domed Universe (Picador, £9.99), mid-generation Northern Irish Colette Bryce, now part of the English poetry establishment, has found her topic. This short-ish book is one of the best accounts of the Troubles to emerge in British verse. The synthesising effect of memory is distilled in poems set largely in childhood. Gravitas comes from what would elsewhere be trivial, the unflashy free-verse form and the ordinariness of reported detail: "we mimed the prayer/ of the Green Cross Code", "We'd cross the border in our red Cortina", "The republicans/ rest their plates on their knees and gobble up their dinners."

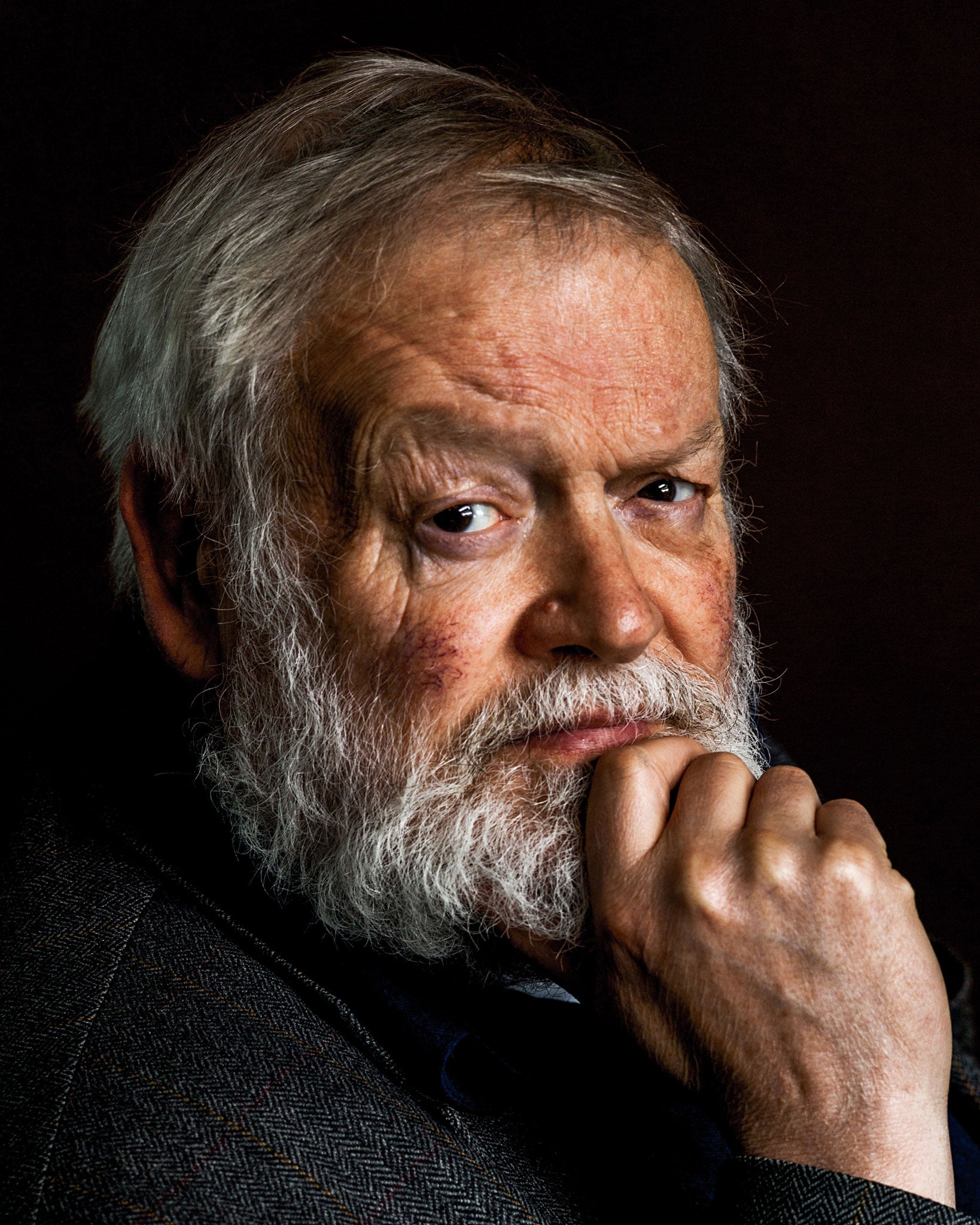

The second part of Michael Longley's The Stairwell (Jonathan Cape, £10) is an elegiac sequence for his twin, Peter. Matching titles introduce gemlike, mainly short poems, many of which return to Homer, as his poetry of the Great War has long done. The Homeric enobles: something Derek Walcott has also discovered. Longley makes it magical by using the myth as palimpsest, or shape-shift, so that a poem is both, "In Bristow Park, when we were boys/ And GIs trotted, after the War" and "Patroclus harnessing Xanthus/ And Balius". This senior poet uses tender directness to allow himself to play the Holy Fool, showing us that what is huge and abstract, like death, is also as intimate and simple as wild flowers at Carrigskeewaun. As in all true poetry, the geographically particular becomes general in its meaning, for both the poet and his reader.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments