Philip Larkin: Misogynist, racist, miserable? Or caring, playful man who lived for others?

Larkin's reputation has taken a knocking. But a new book by James Booth argues that the poet was affectionate, witty, entertaining and kind, as hitherto unseen letters, sketches and 'selfies' reveal

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Affection for Philip Larkin's work is almost universal. He is more frequently quoted than any other poet of his time: "Sexual intercourse began/In nineteen sixty-three"; "What will survive of us is love"; "Never such innocence again", "The sure extinction that we travel to".

His poems evoke the widest range of moods, from the heart-warming celebration of The Whitsun Weddings to the bloody-minded zest of Toads; from the yearning of An Arundel Tomb to the despair of Aubade. His poems, each crafted to be "its own sole freshly-created universe", have lodged themselves familiarly in our minds. A single phrase or word may bring to mind a whole poem: "almost-instinct", "bright incipience", "the exchange of love", "we shall find out", "afresh". Larkin's words possess what Martin Amis has termed "frictionless memorability".

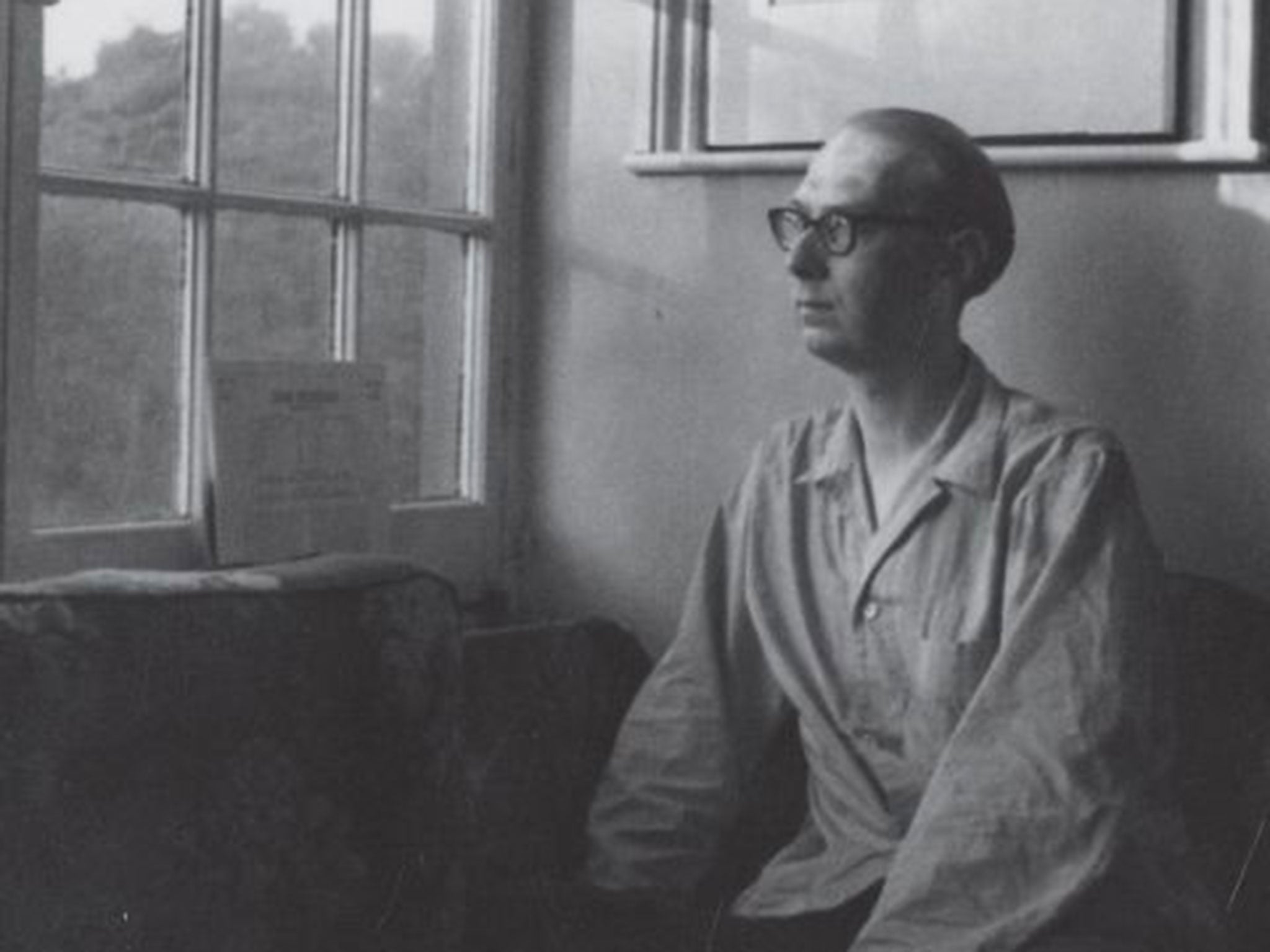

His visual image, in photographs by Fay Godwin and in innumerable caricatures, evokes a more ambiguous response. He was himself a talented photographer who constructed a deliberate record of his life as no poet had done before him. When I emptied the contents fof his house in 2001, I found "snaps" of his mother and lovers and unpublished self-portraits, some of them apparently taken by delayed action shutter-release while he was alone, anticipating the modern "selfie".

He created a sequence of photographic self-interrogations, by which, like Rembrandt, if on a more modest scale, he dispassionately recorded his development and physical decline. Some are "poetic", some lugubrious, some scathingly self-mocking. One image of 1974, clearly self-taken (the head is positioned too close to the top of the frame), seems designed to illustrate Aubade, begun in that year:

"… Not to be here,

Not to be anywhere,

And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true."

Larkin was aware of the capacity of his physical appearance to generate negative responses, and attempted to control his public visual image. He wrote to Fay Godwin that he had given Faber "vehement instructions" not to use one group of her photographs, determined that "the Boston Strangler" will not reappear.' Such an image nevertheless features on the jacket of the current Selected Poems, its bleak glare lending support to Martin Amis's contention in his introduction that Larkin had "no emotions, no vital essences, worth looking back on", but "siphoned all his energy, and all his love, out of the life and into the work".

For though Larkin is one of our best-loved poets, he is also the man we love to hate. Following the publication of Anthony Thwaite's Selected Letters in 1992 and Andrew Motion's official biography, A Writer's Life, in 1993, Larkin fell spectacularly from grace. "Mr Nice tackles Mr Nasty" read the headline above an interview with Motion in The Independent. More recently, reviewers of The Complete Poems, published in 2012, declared that, moving though his poetry may be, Larkin was "a singularly unattractive man", "a vile mess". Some commentators go further, following Lisa Jardine and Tom Paulin in uncovering his "sexist and racist tendencies": "the sewer under the national monument". One reviewer declared of Archie Burnett's commentary in The Complete Poems: "The only thing we're reminded of is what a shit Larkin was in real life."

I do not assume that poets are bound to be likeable or virtuous. But, as I interviewed Larkin's surviving friends, I found myself doubting whether life and art could really have been so deeply at odds with each other. The women with whom Larkin was involved, his literary friends, his library colleagues, all rejected the Mr Nasty version. They remembered him with affection, as witty, entertaining, considerate and kind. And could it really be that the author of the heart-rending Talking in Bed, the euphoric For Sidney Bechet and the serene Here, had no emotions? It seemed that Larkin's negative public image was built neither on the evidence of those who knew him, nor on his poetry.

Jean Hartley, a friend for 30 years, was struck by his unaffected empathy: "He gave his full attention to everyone he had dealings with. I never had the feeling that he was waiting for a gap in the conversation in order to inject his own views. He seemed invariably to follow one's train of thought rather than his own." In his poems, he enters into the feelings of a Victorian rape victim, of a new-born lamb in a snowy field, of a widow weeping over her faded love songs, of an ebullient literary poseur off on a freebie. At one point, he considered as the title of his third volume of poetry, the wryly ambiguous "Living for Others".

He wrote regularly to eight long-term correspondents, presenting to each a version of himself modulated according to their expectations: brilliant jokes and prejudice for the historian Robert Conquest and the novelist Kingsley Amis; witty, lugubrious observations on life and art for the liberal-voting art historian, Judy Egerton, and the poet Anthony Thwaite; measured "Anglican" conservatism for the novelist of manners, Barbara Pym; affectionate chat for the innocent Catholic library assistant, Maeve Brennan, and his lonely widowed mother.

On the publication of his Selected Letters, this exercise in living for others led to him being accused of duplicity. His correspondents discovered that he was not the man they had taken him for. Maeve Brennan was dismayed by his four-letter words; Amis was baffled by his sentimentalism. Commentators made the mistake of identifying the most pungent, transgressive passages with the "real" Larkin. All these Larkins are real. But all have a provisional element; sometimes heavily provisional. As his creative confidence declined in his later years, for instance, his letters to Amis and his life-long lover, Monica Jones, projected for their approval a fictional version of himself far indeed from the poems he was writing at the time.

There is indeed a paradoxical relationship between Larkin the poet and Larkin the man, but it is not, as frequently represented, between fertile artist and sterile man. Rather it is that sketched in his poem Sympathy in White Major: between lonely, self-possessed artist, and loyal friend and lover, attempting, to a fault, to be all things to all men, or (more usually) women. He preserved his inviolability as an artist, by keeping even his most intimate lovers and friends at a distance. For a poet as emotionally susceptible and self-doubting as Larkin, this was a necessary strategy. But it involved a heavy burden of guilt and self-reproach. In his personal relationships, Larkin was always ready to put himself in the wrong. As John Banville has said, self-depreciation was not second but first nature to him.

In 1979, Larkin asserted: "I've always been right wing." This is not true. In a letter to Monica written a quarter of a century earlier he had insisted on his "prejudice for the left".

In a passage from a letter of 1953, published for the first time in my biography, he attempted to defuse an obscure quarrel between them: "Well dear […] even if we neither at bottom care, the fact does remain that you explode to the right & I explode to the left." Monica did, in fact, care about politics in a way he did not. But he characteristically evades the quarrel by complementing her on "making a better job" of defending her explosions than he.

He then neutralises the issue by drawing a caricature rabbit-Monica on a soapbox above a poster reading "Speed up the burrowing programme", facing a seal – Larkin, also on a soapbox, above a poster reading: "No creature comfort without work."

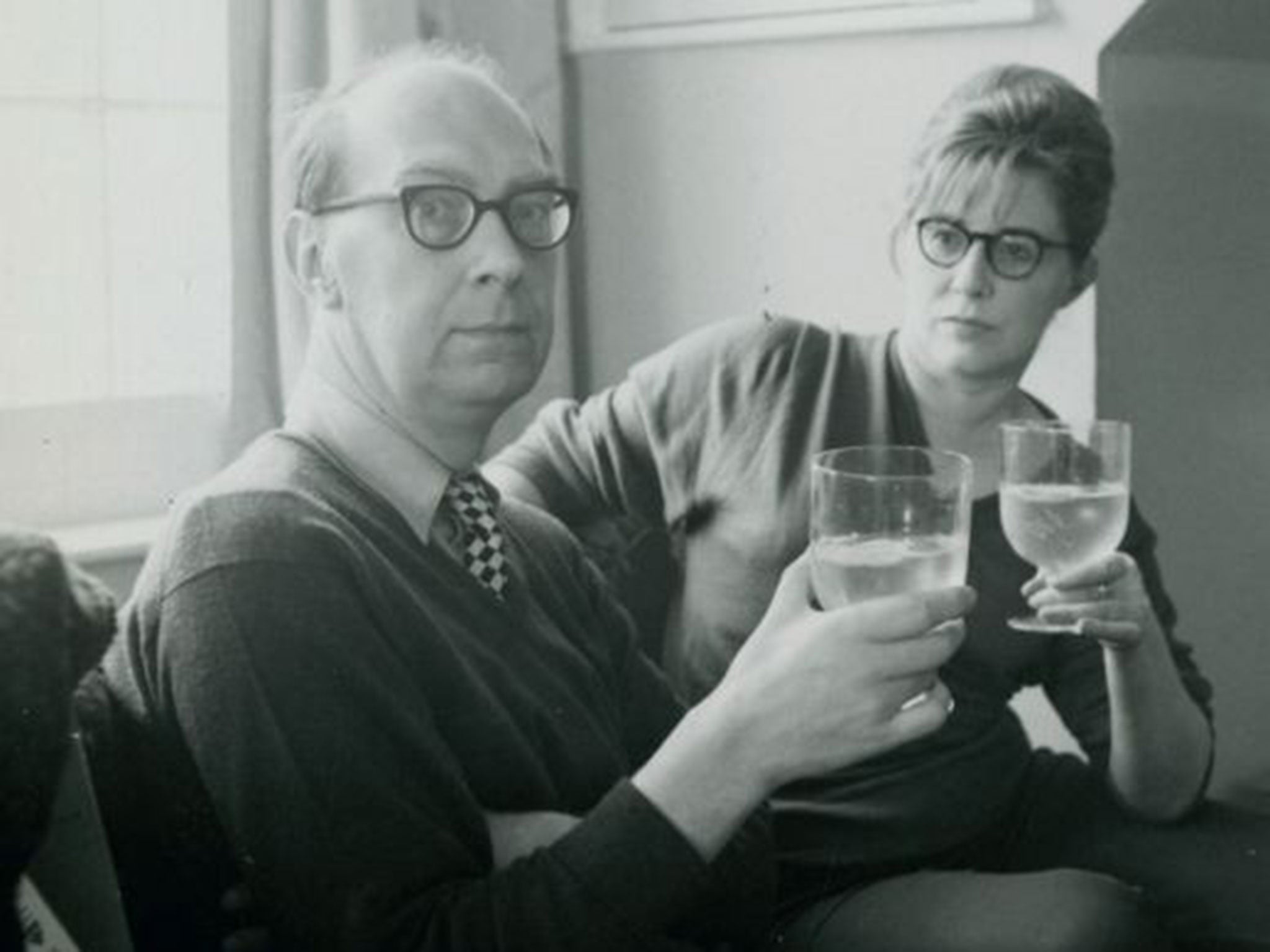

The relationship with Monica Jones shows a constant negotiation between the man living for another, and the artist, intent on his vision. When Larkin first met Monica in 1946, as a colleague in Leicester University College, he was drawn by her vulnerable beauty and edgy social ineptitude. But she held rigid prejudices that stayed with her all her life. Once, at the home of Ann and Anthony Thwaite, she broke into a conversation: "What can you expect when they're Jews!" Larkin's initial reaction to her was one of empathetic identification. During the late 1940s, he worked on a novel whose centre of consciousness, Augusta Bax, is transparently based on her. In a surviving draft, Augusta complains to her visiting mother about a Jewish refugee colleague, Mrs Klein, who "isn't a lady", eats "huge goulaschy messes" on the shared kitchen table, and has recently lost her husband: "I gather the Nazis decided they could get along without him. If he was anything like her I appreciate their point of view for once."

Though the later parts of the novel were never written, it is clear from Larkin's plot outline that Augusta's callous anti-Semitism was to be dispelled as she came under the influence of Mrs Klein's American relatives, a family of '"Wonderful loving Yanks", who were to give her a job as companion to their delinquent daughter and spirit her away to the United States. Larkin kept this novel entirely secret from Monica. When he finally abandoned it in 1953, he wrote to Patsy Strang: "It should be largely an attack on Monica, & I can't do that, not while we are still on friendly terms."

In 1954, his protective feelings for Monica deepened when Kingsley Amis, jealous of this rival for Philip's affection, depicted her as the neurotic, manipulative Margaret Peel in Lucky Jim. The final seal was set on his commitment to her in 1959 when both her parents died and she fell into deep depression. After this he could never desert her. But, loyal though he was, he never fully submitted to her version of him. Monica considered the right-wing humorous magazine Punch "the backbone of England". Exploding to the left, he condemned its heartless celebration of the arrival of myxomatosis in Britain, telling her "the New Statesman would never offend in that way, and I judge them accordingly".

The famous photograph which Monica took of the poet sitting inscrutably on the boundary-sign "England" summarised for her an essential bond between them. Larkin, however, had expressed his instinctive view in an earlier letter: "My God, surely nationalism is the surest mark of mediocrity!" Apart from the commissioned poem, Going, Going (which he called "thin ranting conventional gruel"), his poetry features the word "England" only in neutral or uncomfortably ironic contexts: in I Remember, I Remember (Coming up England by a different line), The Importance of Elsewhere (Living in England has no such excuse) and Naturally the Foundation will Bear Your Expenses (O when will England grow up!). For Larkin, "elsewhere" was always more comfortable than "home".

In politics, so also in poetry. Monica, it is often repeated, suggested the key word blazon in An Arundel Tomb, and it has been assumed that she influenced his poems more widely. However, her views were crude compared with his. She was hostile towards symbolism, the source of Larkin's most sublime transcendences ("Such attics cleared of me! Such absences!") In a pattern repeated many times in the letters, he deferred to her on the surface, while ignoring her ideas in practice:

"Of course I agree with all you say about symbolism! How could I not? My mind is stodgy as usual tonight, but I know I'm with you there, like a rabbit huddled against a warm pipe outside the greenhouse on a frosty night.

"As soon as you start meaning one thing by saying another you open up a gap and the thing sounds hollow. Rabbits wouldn't understand symbolism."

But the more he proclaimed the traditionalist philistinism which Monica required of him, the more gaps between saying and meaning opened up in his poems. In Money, the poet listens to money "singing":

"… It's like looking down

From long French windows at a provincial town,

The slums, the canal, the churches ornate and mad

In the evening sun…"

In 1964, at the beginning of his seventh workbook, he had written: "Never write anything because you think it's true, only because you think it's beautiful." Monica would have had no truck with this intense aestheticism. Like Kingsley Amis, she insisted that Larkin reduce himself to her version of him. Fortunately for his poetry, he refused to do so.

'Philip Larkin: Life, Art and Love', by James Booth (Bloomsbury, £25), is out on 28 August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments