France’s latest literary sensation hates men. Or does she?

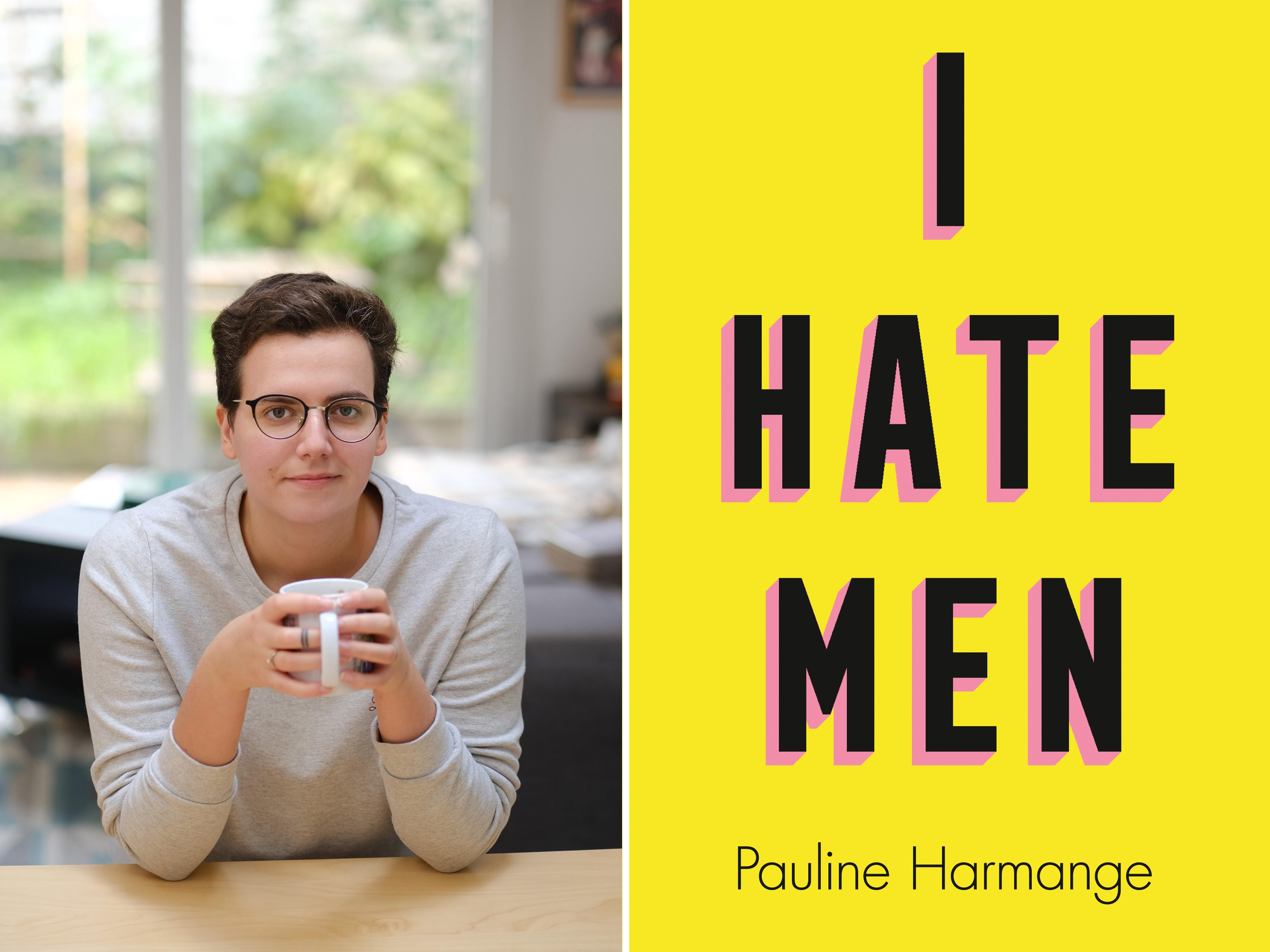

Pauline Harmange’s debut book has caused controversy back home and French officials have tried to ban it on the grounds of its title. But, the author tells Clémence Michallon, her misandry is merely acknowledging structural sexism

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Pauline Harmange didn’t think her book about misandry was destined to make a big splash. Not by lack of confidence, or because she thought the world wouldn’t care. But she was working with a small, independent French publishing house, which she thought was the perfect path to a “tranquil” debut. Writing about feminism, as Harmange does, often means having to cope with backlash and online abuse, so choosing a relatively modest platform made sense to her. “I was thinking, ‘That’s great – my dream was to be published one day. This is a good first experience, everything’s going to go very peacefully,’” she says. “And then the opposite happened.”

The French government got involved. On 31 August 2020, Mediapart, an independent investigative website, reported that Ralph Zurmély, an adviser to the country’s ministry for gender equality, had emailed the publishing house ordering it to withdraw the book. Moi les hommes, je les déteste (which translates to I Hate Men), he argued, was an incitement to hatred based on gender – a criminal offence in France. His claims were based on the book’s title and summary on the publisher’s website, rather than its contents.

Monstrograph, the publishing house working with Harmange, had already printed 400 copies of the book. After Mediapart’s story ran, it quickly became clear that this wouldn’t be enough. Zurmély’s attempt to censor the volume had the opposite effect. I Hate Men, a feminist examination of the dislike of men, was flying off the digital shelves. As a non-profit run by two people, Monstrograph struggled to keep up. Within days, the original edition of I Hate Men was out of print. Monstrograph passed the torch to a larger publishing house, the prestigious Éditions du Seuil. Publishers outside of France started paying attention too.

By the time Harmange and I speak, I Hate Men is set to be translated into 16 languages. The author is still stunned, though she’s learning how to manage the overwhelming media blitz. The number of translations seems especially surreal. “To me, this makes no sense,” she says. “It’s something that doesn’t exist and, most of all, that wasn’t supposed to happen to me.”

Harmange, 25, graduated with a degree in communications in 2018. For a while, she worked as a freelance copywriter and set up a blog, where she still writes about books, TV shows, films, and her own life. I Hate Men grew out of a 2019 blog post about the exhaustion of existing as a woman and a feminist. Monstrograph’s editors got in touch and asked if she’d be interested in expanding it into a book. Now, she’s a full-time author, with another non-fiction book planned for 2022 about abortion.

“I have a lot of work that’s so exciting, so interesting, and exactly what I dreamed of,” she says, the excitement clear in her voice. “So this is my life now.”

The book that changed Harmange’s life is short (the English version totals 78 pages) and, she says, “very personal”. It’s a treatise drawing from her own experiences to make wider observations about male domination. Each chapter focuses on a specific theme, such as sisterhood, misogyny and the trappings of straight relationships. Harmange defines misandry, the essay’s central theme, as “a feeling many women experience, even if they don’t dare admit it, which consists in thinking that men in general aren’t people you can automatically trust”.

“We want to think that we’re all nice people, but structurally, men as a group aren’t nice to women as a group,” she continues. “So it makes sense to be wary of them, to not want to be especially close to them, and to ask them to make a lot of effort before we accept them into our lives.”

Defining misandry as a dislike of men isn't inaccurate, but it is reductive. The dislike Harmange speaks of isn’t personal, or mean, or – contrary to Zurmély’s claims – an incitement to hatred. It’s an acknowledgment of structural sexism, and of those who take positive actions to limit its impact. Or, as Harmange puts it in her book:

“I hate men … By default, I have very little respect for any of them. Which is funny actually, because ostensibly I don’t have any legitimacy when it comes to hating men. I chose to marry one, after all, and I have to admit that I’m still very fond of him. That doesn’t, however, stop me from wondering why men are as they are. They’re violent, selfish, lazy and cowardly. It doesn’t stop me wondering why we women are supposed graciously to accept their flaws ... even though men beat, rape and murder us.”

The backlash against Harmange has played out both privately (in her DMs) and publicly (in some of the media coverage). She currently gets three to four messages a day – far fewer than she did in September, right after I Hate Men first came out in France. Attacks range from low-level jabs at her physical appearance to attempts to engage with the thesis of her book without actually reading it. The irony being, of course, that every insult, every malevolent jab, helps prove her point. “There is violence in misogyny. It’s indissociable from it,” she says. “Misandry, on the other end, is just a defensive posture to preserve yourself.”

One of the low-hanging-fruit arguments often levelled against Harmange is this: what if someone were to write a book called I Hate Women? Wouldn’t it cause considerable outrage? To Harmange, the idea is a non-starter. “[That book] would necessarily be terrible,” she says. “There would be no argument to develop. You can’t switch out the oppressor and the oppressed. That’s bad faith.”

From childhood, Harmange was well positioned to challenge gender norms. She realised early on that her parents “didn’t abide by every code, every stereotype tied to straight couples in a patriarchal society”. Her mother was the household’s highest earner. When her two younger brothers were born, her father took two years of parental leave – a rarity in France, where the legal duration of parental leave will increase from 14 to 28 days in 2021. Growing up, she didn’t identify with traditional norms of femininity. Through the internet, social media and community organisations, she developed a political conscience and an activist’s mind.

Much has been made of Harmange’s Frenchness in international media coverage. This tends to happen with French creators, as if every strand of their identity has to be analysed in the context of the country’s past and current social context. For Harmange, this means that some people are tempted to tie her ideas to a specific kind of French sexism. Think Emily in Paris and its string of libidinous, boundary-crossing Gallic guys. French men, our collective imaginary tells us, conflate sexism and seduction. In France, this is used as an excuse and a way to dismiss people who call out misogyny. Outside of France, it can be used to shrug off responsibility: if the sexism Harmange describes is specifically French, then we, non-French people, are off the hook.

But misogyny is universal. Yes, it affects different people differently, and it can present itself in myriad ways. That doesn’t mean it’s not everyone’s problem.

“Sure, catcalling isn’t the same [in every country]. Some things are really different,” Harmange agrees. “But I think that’s also a way to avoid taking responsibility. As if to say, ‘That doesn’t happen where we’re from.’ Sexism is global. It felt like people were saying, ‘Oh, French people are weird, they have really liberated mores, etc.’ That’s partly true, but things are more complex than that.”

At its heart, Harmange’s book is a call to liberation. Her writing is full of hope, unwavering in its trust of other women and their abilities. “If we all became misandrists, what a fabulous hue and cry we could raise. We’d realise (though it might be a bit sad at first) that we don’t actually need men,” she writes in the book’s rousing introduction. “I believe too we might liberate an unsuspected power: that of being able to soar far above the male gaze and the dictates of men, to discover at last who we really are.”

I Hate Men is out in the UK via 4th Estate and will be published in the US on 19 January 2021

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments