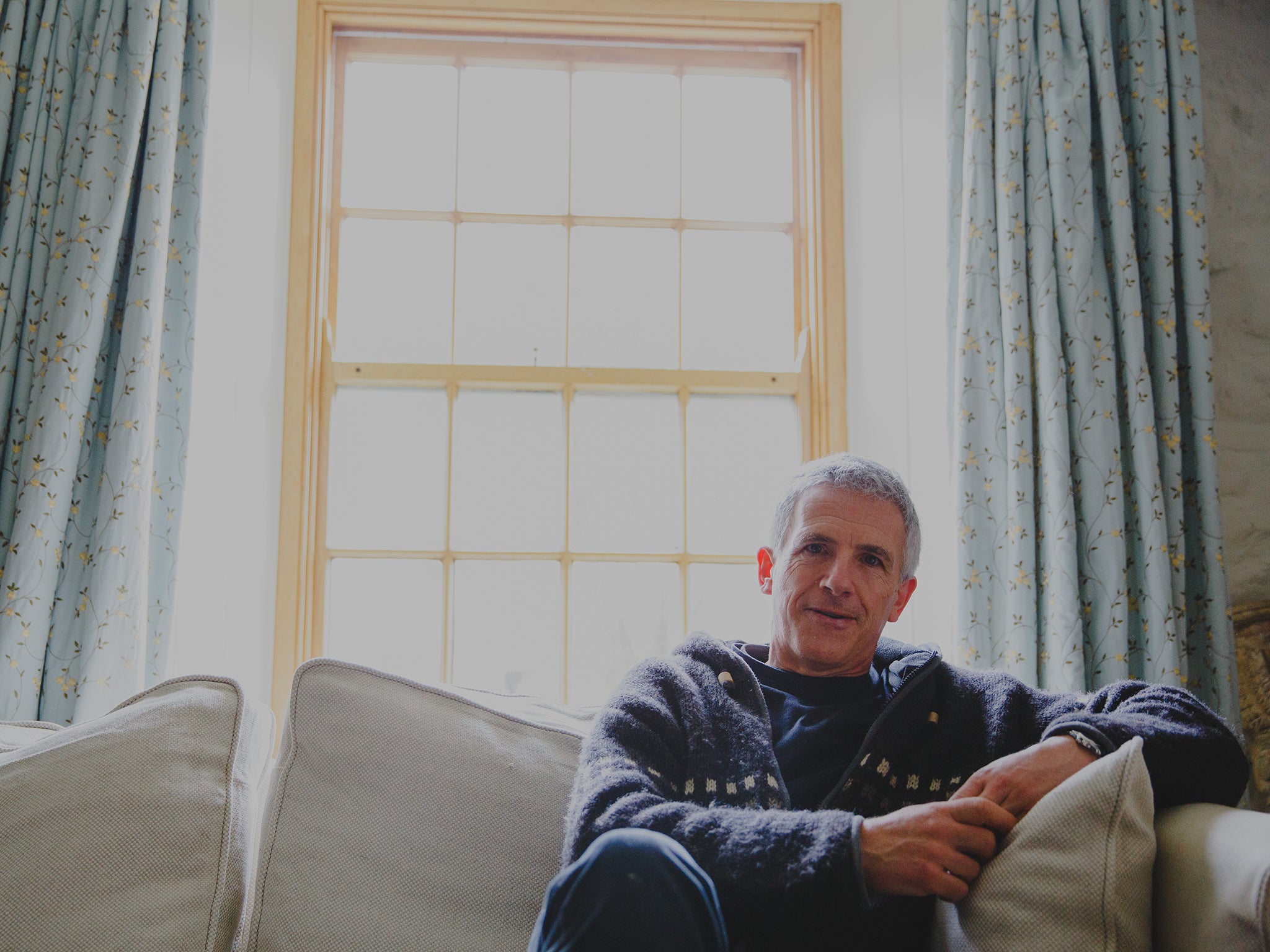

Patrick Gale on A Place Called Winter: 'The challenge was to inhabit a homosexual life where there are no words to describe being gay'

The writer reveals why he turned to the Canadian wilderness for his latest novel

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He’s not as famous as his near namesake, the Tottenham goal-scorer Harry Kane, but the life of Harry Cane intrigued Patrick Gale long before he decided to draw on it in his new novel. Harry, Gale’s great-grandfather, emigrated to Canada in the early 1900s.

“I always knew I had a cowboy grandpa,” says Gale when I visit him on his husband’s farm in the far west of Cornwall. “The mystery was around why he abandoned his wife and child to go and lead this incredibly harsh existence. He’d never worked. He was a man of leisure. My grandmother told me lots of stories when I was growing up but she never talked about Harry.”

At 53, with 16 novels already published, Gale still gets “hideously nervous” before a book comes out. A Place Called Winter, which was selected in this newspaper as a hotly anticipated book of 2015, is his first historical novel and a departure from the Cornish settings of his previous work, A Perfectly Good Man (2012), and his commercial breakthrough, Notes from an Exhibition (2007). “Some of my loyal readers will be disappointed that I haven’t written another Cornish novel,” he says. “But Cornwall has become too familiar to me. It’s hard to put it on the page, to make it fresh.”

It feels pretty fresh this morning, with breeze ruffling the gorse and white horses on the Atlantic, but I understand what Gale means about his readers. I grew up in nearby St Ives and his Cornish novels give me the rare thrill of seeing places I know captured in imaginative prose. That said, where Gale lives, one mile from Land’s End, is so remote it makes Penzance look like a bustling metropolis. The fields, derelict tin mines and villages are a far cry from the confines of his unusual childhood.

“My father and grandfather were both prison governors,” he explains. “I was born in Wandsworth prison and lived there until I was six, so I have an institutionalised background.” He won a scholarship to Winchester College, where he sang as a Quirister and learned to play the cello. “I wanted to be a musician until I was in my teens but I grew up in a very bookish household. E M Forster, Joseph Conrad and George Eliot made me realise a novel was more than a story, that it could leave you changed and extend your empathy.”

Before I can ask my next question, Gale apologises for the cake he has baked for us (“Sorry, this is very gooey…”) but his cinnamon and walnut sponge is delicious, a sign of how at home he is here. His office, where he writes while listening to classical music, is a converted bull shed, so was moving to the farm a decade ago a culture shock? “At the start it was because I had to do lots of manual labour. We used to grow cauliflowers and worked every day in winter, harvesting by hand. So there was some of that element of shock which Harry experiences when he begins homesteading.”

In the two-and-a-half years he worked on A Place Called Winter, did Gale retrace Harry’s journey to the Canadian prairie? “I spent three months there and, although Winter itself is a ghost town now, I had the map coordinates for Harry’s farm so I was able to track it down precisely. I found it terribly moving that his acres were still being ploughed.”

In the novel, the land is practically lawless, Mounties are few and far between, there’s rape, murder and Harry is terrorised by the thuggish Troels Munk. “It surprised me how unpleasant and frightening certain scenes became,” says Gale. “I scared myself. When I went to Canada and stayed in a cabin in the middle of nowhere, I got a sense of how vulnerable Harry would have been. He needed his gun.”

The novel begins in a Canadian psychiatric hospital, where Harry undergoes hypnosis therapy, and loops back through his life, building suspense. The fictional Harry is forced to emigrate by his wife’s family after his affair with a man is exposed and, although Gale is pretty sure his ancestor wasn’t gay, filling in the gaps this way lets him explore themes which are close to his heart.

“The challenge was to inhabit a homosexual life in a time when there are no words to describe any of the things the character feels or does. It is quite literally a story about the unspeakable. At a stage in our history when, at least in Europe, gay people have got every right they could possibly want, it’s important to remind ourselves how recently that’s come about and how easily it could be taken away again.”

The First World War is skilfully brought to bear on Harry’s story and that setting allows Gale to consider the role of women too. Harry’s English wife and sisters-in-law are counterpointed by hardy, liberal Petra whom he befriends in Canada: “There were such constraints on women to be ladylike which was all very well in the drawing rooms of Kensington but a different matter on the prairies,” says Gale, whose novel also dramatises the plight of Native North Americans: “The question of what constitutes civilised behaviour is at the heart of the plot. Is civilisation just about populating an area or is it more complicated? The Cree, the Native tribe Harry encounters, had an old, complicated civilisation which settlers wiped off the map. The inequities in Canadian society are every bit as bad as those in Australia, in terms of the bitter legacy of colonisation.”

Critics have highlighted compassion as one of the qualities in Gale’s fiction, and it shines through again, but I was surprised by Harry’s willingness to acknowledge the reasons for Munk’s brutality. “Munk is probably a psychopath,” says Gayle, “but my difficulty with writing a negative character is that, in the course of the book, I come to understand some of their behaviour and at least halfway to forgive them.” Does he root for his protagonists? “Totally. The thing that really interests me in the fiction process is working out what makes somebody become the person they are. I’ve often thought the career I could have had was psychotherapist.”

His readers are glad he stuck with writing, although he still has doubts: “My father inculcated a strong sense of social duty in me and I feel I don’t do a very useful job. I feel I’m just indulging myself.” Then he laughs, aware perhaps that, as with his baking, he’s being over-modest.

Extract from the book:

‘The attendants came for him as a pair, as always. Some of them were kind and meant well. Some were frightened and, like first timers at a steer- branding, hid their fear in swearing and brutality. But this pair was of the most unsettling kind, the sort that ignored him. They were talking to one another as they came for him …’

A Place Called Winter, by Patrick Gale, Tinder Press, £16.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments