Oskar Schindler and me: Holocaust survivor dies too soon to see memoir hit shelves

Leon Leyson was one of the youngest concentration camp victims to be rescued by the industrialist, but he died too soon to see his memoir published

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

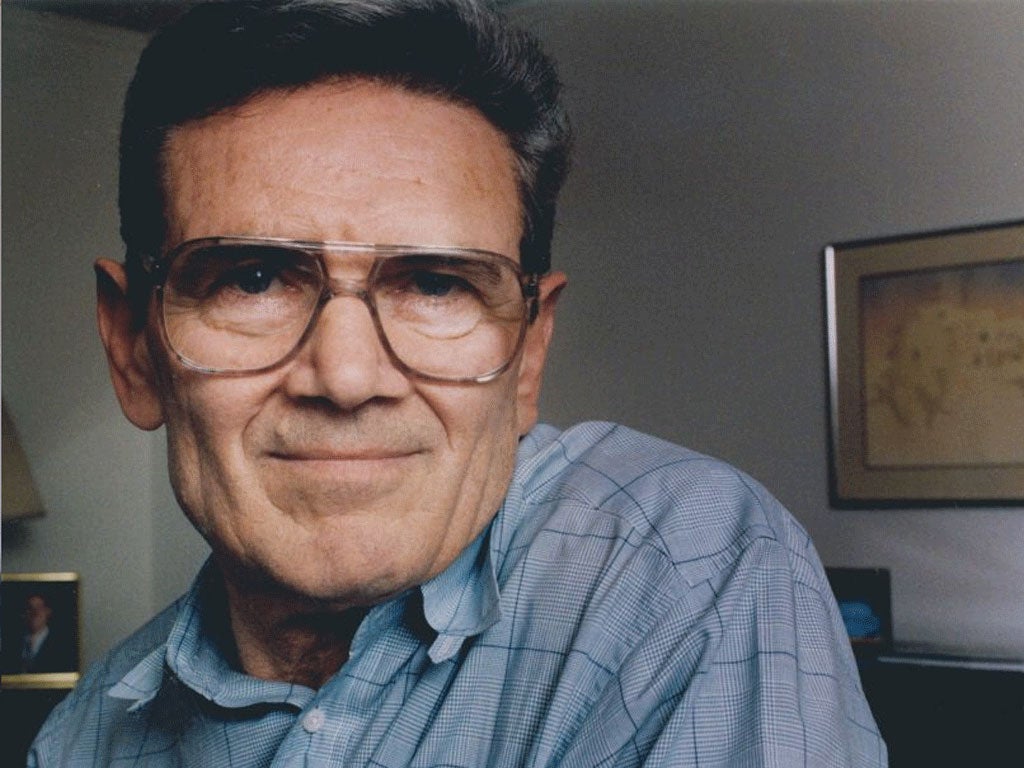

Your support makes all the difference.He was one of the youngest Holocaust survivors to be saved by Oskar Schindler, and he waited almost 70 years to tell his story. Sadly, Leon Leyson died before he could see his memoir published. The extraordinary, horrifying and heart-breaking book The Boy on the Wooden Box, about a 13-year-old who found his way onto Schindler’s famous list, was released in the US by Simon & Schuster’s children’s division today.

Caitlyn Dlouhy, editorial director of Atheneum Books – a division of Simon & Schuster’s – which picked up the manuscript, said: “Within 50 pages I knew this was an astonishing piece. It was told without rancour or anger. He was just telling the story the way a little boy would have.”

She continued: “It’s such a shame he never saw it in print. For his wife Lis it is so bittersweet. She is so happy at the reception of the book; that it came out beautifully. She knows how proud Leon would have been but she can’t share it with him. It has to be so hard.”

Mr Leyson was born Leib Lejzon in 1929 and was just 10 years old when the Germans invaded Poland and his family were forced to move from Krakow to a Jewish ghetto in Podgorze, a suburb of the city.

They suffered regular harassment and had little food before the persecution intensified and the Jews were rounded up and sent to concentration camps. The book includes stories of his hiding from the Nazis; on one occasion he sat on a roof beam in a shed for two days as gunshots and screams grew louder.

The family was sent to the Plaszow camp in 1940, and Mr Leyson only managed to rejoin his family after sneaking past a guard at huge personal risk. He described stepping through the gates like “arriving at the innermost circle of hell” adding the moment he arrived “I was convinced I would never leave alive”.

The camp’s commandant was the infamous Amon Goeth. Among the frequent brushes with fate, Mr Leyson once had his leg bandaged at the infirmary, finding out later that Goeth had all the patients arbitrarily shot moments after he had left.

He described the living conditions – being too tired and hungry to care about the lice crawling through his hair and clothes, of harassment from the guards and having the same meal every day: hot water with a little salt or pepper and perhaps a bit of potato skin.

The camp commandant once had the young boy whipped on a whim. Those receiving the punishment had to call out the number of each of the 25 lashes – with whips that had ball bearings on the end – and if they got the count wrong, the guard would start again. It left him unable to sit or lie down for months.

In 1943, Schindler hired him and his mother to join his father and brother in Krakow. It was on the night shift that he got to know Schindler personally – writing that despite being a Nazi “he acted like he cared about us personally”. In the factory he was so small he had to stand on a box to operate the machinery, which gave his memoir its title.

Mr Leyson wrote of a man who was “tall and hefty with a booming voice” and after initially fearing him, looking forward to his visits. When the factory was moved to Czechoslovakia Schindler saved the family’s lives again, pulling them out of the line, heading for the death camps.

In a final act of salvation, in April 1945 with the Germans fleeing, they were ordered to murder all the Jewish workers in the Brinlitz camp. Schindler managed to thwart the plan and have the SS officer in charged transferred out of the area. He freed the workers giving them each a bottle of vodka and a bolt of cloth. Mr Leyson emigrated to the US in 1949 at the age of 20, five years after he was liberated from Czechoslovakia. He served in the US army during the Korean War, as he wanted to give something back to the country that had taken him in, and taught at Huntington Park High School in Los Angeles for 40 years.

Mr Leyson was to meet Schindler again some 20 years after the end of the war. Sweaty palmed at the thought of seeing him again, and wondering whether he would recognise a 35-year-old married army veteran, Schindler immediately picked him out of the welcoming committee at Los Angeles Airport saying: “I know who you are. You’re little Leyson.”

This year marks the 20th anniversary of Steven Spielberg’s award-winning film Schindler’s List and it was the film that prompted Mr Leyson to open up about his experiences for the first time after he was tracked down by a reporter.

In the book he even referenced one scene from the film where Schindler, played by Liam Neeson, pulls his accountant Itzhak Stern from a train bound for an extermination camp called Belzec.

What the film did not show was Schindler, in real life, spotting Mr Leyson’s brother – who refused to get off because his girlfriend Miriam was on the train. Both died at the camp.

The work had been seen as a companion piece to Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl. “They are obviously very different books,” Ms Dlouhy, the publisher, said. “However the two of them never gave up hope. There’s always a chance that might be there. As tragic as it all is, it’s all about hope.”

She added: “He was continually grateful for where his life ended up. He refused to live in self-pity.”

He married Lis, a fellow school teacher in 1965, and they had two children. She said in the book’s afterword, written after his death: “The driving force that kept Leon telling his story year after year, even though he relived heartbreaking grief each time he spoke, was to honour the memory of his family and the millions of other victims of the Holocaust.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments