Books of the month: From Will Self's memoir to a book on the political psychology of Donald Trump

Martin Chilton reviews five of November’s best books for our monthly book column

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Erin Morgenstern’s captivating new novel The Starless Sea refers to a “a book-centric fantasia” – and there is certainly a wonderfully eclectic mix of styles and forms in this month’s publications.

Julian Barnes’s tale of La Belle Epoque, built around the story of the celebrated French doctor Samuel Pozzi, is fascinating history, biography and philosophy rolled into one. In The Man in the Red Coat, Barnes is the ideal guide to a hysterical “hyperventilating era” (1870-1914) when “prejudice could swiftly metastasise into paranoia”. It was also a period when the gun lobby wielded significant power in French politics. More than a century later, the United States has its own pro-gun president, who has boasted about owning a permit to carry a concealed weapon.

Barnes describes La Belle Epoque as a “narcissistic” age, and that word appears over and over in a revealing new study of the often-hyperventilating Donald Trump. Dangerous Charisma is written by the CIA’s Jerrold M Post, who is considered the founding father of political personality profiling.

Novelist Barnes also remarks that biography is “a collection of holes tied together with string”. In The Contender, a 700-page book on Marlon Brando, William J Mann attempts to pull together the definitive life story of the man who transformed the world of acting in the 20th century. Brando was known for serious roles, but he also had a “sense of the absurd” that lasted until his death. At 77, while filming The Score, “he rigged up a remote-controlled fart machine that went off whenever Robert De Niro sat down on the couch”.

There are a host of novels this month by beginners and bestsellers. As well as debuts from former solicitor Amanthi Harris (Beautiful Place) and Who rock star Pete Townshend (The Age of Anxiety), there is new fiction from old hands Michael Crichton, Martin Cruz Smith, David Baldacci and Simon Kernick. Few modern authors can match the selling power of Mitch Albom, however, whose moving true story Finding Chika is sure to please the fans who have bought more than 39 million copies of his books.

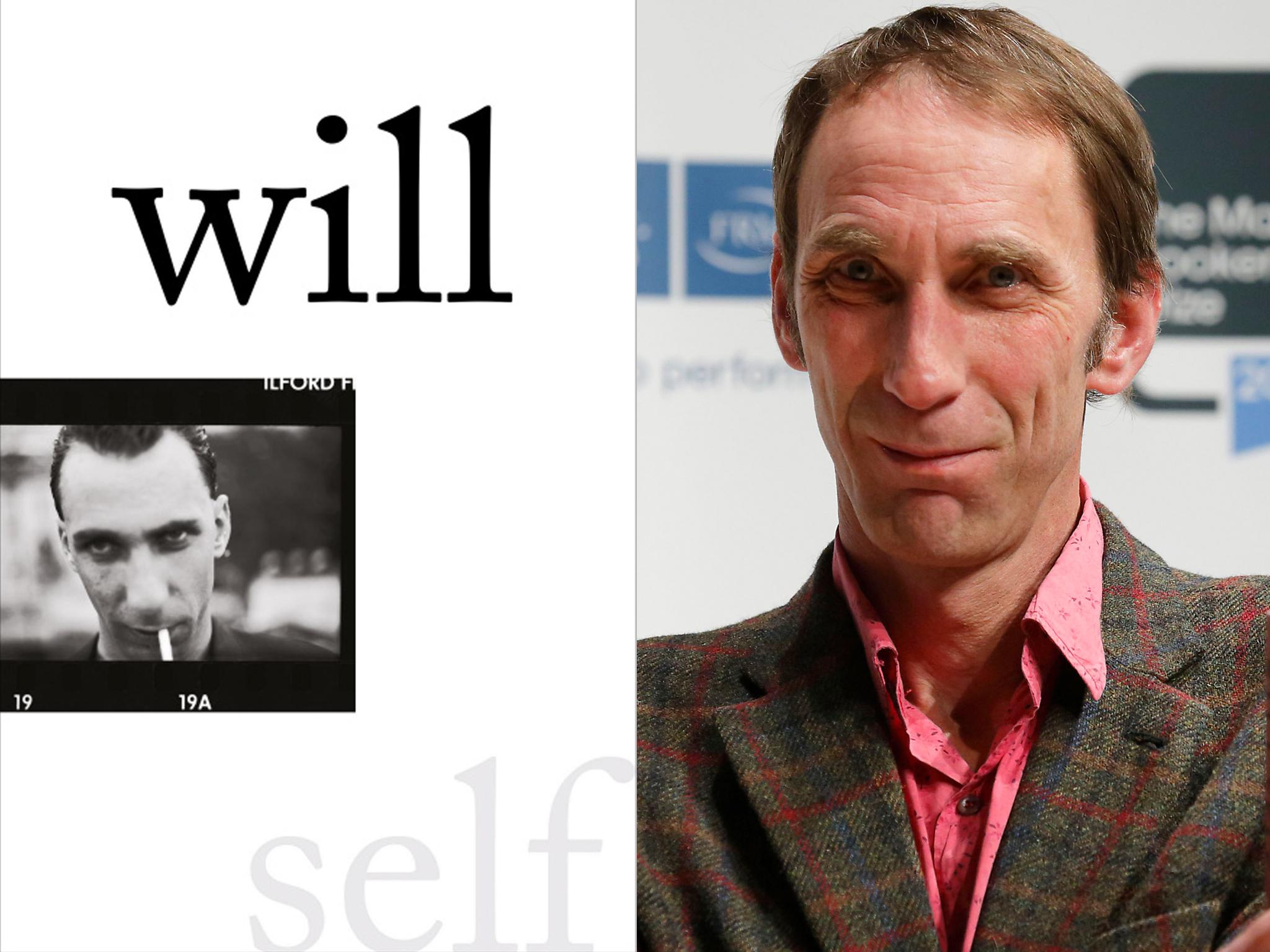

Scarlett Thomas’s Oligarchy, which has been bought for a television adaptation, is a darkly comic tale about the tribulations of the daughter of a Russian oligarch sent to an English boarding school. Parts of Oligarchy are set in London, a city that Pozzi’s fictional friend Jean des Esseintes found to be odd back in 1888. Esseintes remarked on the strange sight of “Londoners marching along with eyes fixed ahead and elbows glued to their sides”. That still foreboding city is the setting for much of Will Self’s memoir Will, which recounts visits to squats in Clapham, grubby dens in Kentish Town and flats on the Broadwater Farm Estate to buy drugs.

In the latest of our books of the month columns, we review five books published in November 2019.

The Starless Sea by Erin Morgenstern ★★★★☆

Erin Morgenstern’s fiction radiates with the excitement of someone discovering a magical world within the pages of a book. The Starless Sea, which comes seven years after her triumph with The Night Circus, is another enchanting read. Her latest protagonist is student Zachary Ezra Rawlings, who takes a break from role-playing video games to visit the university library in Vermont. He had, writes Morgenstern, “a near compulsive need to let his eyes rest on paper”.

Zachary finds a beguiling, ancient book with unnerving details about his own life which seems “too perfect to be fiction”. The book he finds in the library contains a series of clues – a bee, a key and a sword – that leads him, via a masquerade party in New York, to a subterranean library. This underground labyrinth is a place of imagination and fables. This quest is clearly invigorating for a youngster who is suffering a “quarter-life crisis”.

Morgenstern’s tale has shades of detective fiction, magical fantasy and even Gothic mystery – the character Eleanor is named after a key character in Shirley Jackson’s 1959 classic The Haunting of Hill House – but her ambitious 512-page novel is really an ode to stories and storytelling itself, and the joy of reading. The UK edition has a beautiful cover designed by Suzanne Dean and once fantasy fans open its covers and let their eyes rest on the sparkling words inside, they are in for a treat.

The Starless Sea by Erin Morgenstern is published on 5 November by Harvill Secker, £16.99

Finding Chika by Mitch Albom ★★★★☆

Mitch Albom’s uplifting, sentimental books have struck a real chord with the reading public. Tuesdays with Morrie is reportedly the bestselling memoir of all time. His new true-life tale is about Chika Jeune, who was born three days before an earthquake wrecked Haiti in 2010. She died seven years later.

When motherless Chika was diagnosed with the terminal disease DIPG – diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma – the author and his wife Janine became her adoptive guardians, bringing her to America for treatment on her brain tumour. An “invader had squatted in your brain”, is the way Albom puts it, in a book written partly in direct address to the child he met at the orphanage he helps fund in Haiti (his proceeds from the book go to Have Faith Haiti Mission).

Although Finding Chika makes for heart-wrenching reading, it is also a tale of resilience and decency – and the memorable cheerfulness of a dying child. “What we carry defines who we are and the effort we make is our legacy,” says Albom.

Finding Chika by Mitch Albom is published by Sphere on 5 November, £14.99

Dangerous Charisma: The Political Psychology of Donald Trump and his Followers by Jerrold M Post ★★★★☆

Dozens of books about Donald Trump have been published in 2019, but few are as clinically analytical as Dangerous Charisma by Jerrold M Post, the man considered the founding father of political personality profiling. Post had a 21-year career with the CIA, during which time he compiled profiles for Jimmy Carter and appeared before congressional committees. He believes he has an “ethical obligation” to write about Trump and he cites The Washington Post’s estimate that Trump supposedly told 4,299 lies during a single year in office.

The book looks at Trump’s upbringing and the effects on his character of a father who repeatedly told him “to be a king, to be a killer”. Post also looks at the influence of another mentor, Roy Cohn, who was “like a second father” to the future president. Cohn, Joseph McCarthy’s right-hand man, “stressed to Trump the importance of keeping his name in the papers”. “Trump has been consumed by dreams of glory since his youth,” writes Post. “For most narcissists, the dreams are not fulfilled, the ambitions are not achieved. But what happens when the dreams of glory are achieved? There is an explosion of narcissism.”

Trump’s sloganeering style of politics has proved immensely successful. Post’s verdict is that his followers “regressed” during a time of crisis, attaching themselves to “a leader who will rescue them, take care of them”. Post argues that Trump has kept up his habit of having rallies “because he needs to continue to thrive off the admiration of his followers as another form of compensation for his insecurity and self doubt”.

Post says the leader of the free world has a remarkably short attention span. Trump’s most frequently-used words are “great”, “win” and “loser”. Trump boasted that he “never reads” and Post reveals that the president’s grammar and vocabulary “is below that of a sixth-grader; indeed, some studies have likened his vocabulary to that of a third-grade level”. That would put him on a par with a child of eight or nine. Post, whose book is published in the US, reveals that the CIA often has to “deliver information to President Trump in a manner that he can best understand, which is largely through visuals like maps, charts, pictures and videos”.

This is a disturbing, depressing book – and there aren’t even any pictures to look at.

Dangerous Charisma: The Political Psychology of Donald Trump and his Followers by Jerrold M Post is published on 5 November by Pegasus Books, $27.95

The Man in the Red Coat by Julian Barnes ★★★★★

“The past is the present’s toy and plaything, gratifyingly unable to answer back,” writes Julian Barnes in The Man in the Red Coat, his delightful amble through La Belle Epoque, that so-called Golden Age from 1870 to 1914. At the centre of the book is Samuel Pozzi, a man Barnes was drawn to writing about after seeing John Singer Sergeant’s 1881 painting The Man in the Red Coat, a portrait of a doctor who was described contemporaneously by the New York Herald Tribune as “the most eminent surgeon in France”.

Barnes makes the case that Pozzi was “a sane man in a demented age”, although his subtle account of a man who rose from Bergerac boy to Parisian high society does not shy from discussing his subject’s feet of clay. As well as being a trailblazing surgeon, Pozzi was an incorrigible seducer – routinely of his own gynaecology patients. His daughter Catherine lamented having “a moral wreck of a father”.

Yet Barnes’s book, which is full of interesting illustrations to accompany the text, is so much more than an account of Pozzi – it is a riveting dissection of an era that was “decadent, hectic, violent, narcissistic and neurotic”. Barnes deftly draws parallels between the gangster imperialism of La Belle Epoque, where the wealthy got wealthier, antisemitism was rampant and “fake news was prevalent”, and our neurotic present, “which believes itself superior to the past but can’t quite get over a nagging anxiety that it might not be”.

The author’s shrewd assessments and droll asides add to the enjoyment of a book filled with a phantasmagoria of odd characters and freakish events. Count Robert de Montesquiou, for example, left a “malicious and misogynistic sign-off” to his former lover Madame Armand de Caillavet: a casket full of her unopened letters. During this delightful meandering, Barnes also divulges memorable tales about Oscar Wilde, Sarah Bernhardt, Marcel Proust and artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler, who is described in a damning triplet as “shabby, syphilitic and insane”.

One recurrent theme is the duels that blighted Paris in this era – there were 150 in a decade – and how an “active gun lobby” in French politics prevented the deadly problem being solved. Pozzi wrote 40 papers on the treatment of bullet wounds and was one of the world’s “leading experts” on gunshot surgery. Alas, Pozzi’s knowledge was of no help when he was shot three times by his own patient, a tax collector who was angry about a scrotum operation that he believed Pozzi had ballsed up. Pozzi died in 1918, as the Golden Age perished in the heat of the First World War.

The Man in the Red Coat by Julian Barnes is published on 7 November by Vintage, £18.99

Will by Will Self ★★★☆☆

Will Self’s memoir about addiction is an intense, stream-of-consciousness-like account of his life as a young addict, told through five “episodes”, starting from when he was 17. Self refers to himself in the third person throughout – in sentences such as “Will likes to quote Turgenev on the subject of enlightenment: What’s the difference between a white void and a black void” – as he casts a jauntily honest eye over his once anarchic lifestyle.

Interspersed amid the self-analysis in Will is an inventory of his prodigious drug-taking – including smoking dope, popping barbiturates and tranquillisers, snorting morphine, injecting smack and “shooting up shit coke” – but the law of diminishing returns kicks in quickly.

The dehumanising effects of addiction were brilliantly explored 70 years ago in Nelson Algren’s The Man with the Golden Arm. Self recalls that one of his “mum’s fave words” was “empathy”. Self’s memoir is vivid but oddly unengaging on a personal level, unlike Algren’s classic. Admittedly, I am doubtless one of the “dumb-f—king-straights” who lack his appetite for real hard drugs. Or even, as it turns out, the desire for a vicarious high.

Will by Will Self is published on 14 November by Viking, £14.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments