No one expects the Spanish Inquisition

The beauty of teen fiction for this Easter holiday is its effortlessness in smuggling in learning

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I'm a sucker for historical fiction, not least because you learn lots without having to make much effort.

I took the same view as a teenager, although there didn't seem to be all that much of it about – apart from the wonderful Rosemary Sutcliff and the prolific Jean Plaidy. Historically inclined young readers have it much better these days.

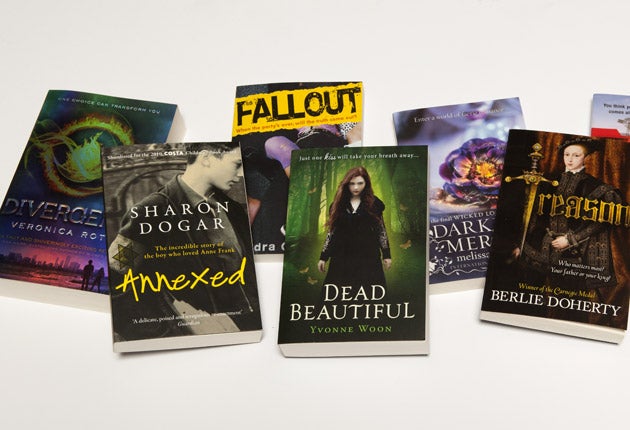

Treason by Berlie Doherty (Andersen, £5.99), for example, is narrated by Will Montague, a page to Henry VIII's only son, Prince Edward, which puts us in the middle of the 16th century. These were dangerous times, of course, and when Will's father is wrongfully imprisoned for treason, and his son and his friend go through dreadful ordeals to get him out, Doherty paints a very vivid picture of the horrors. It's almost Shardlake for young readers.

Set a couple of generations earlier, during the 1490s in Spain and beyond, is another slant on treason and treachery: Theresa Breslin's Prisoner of the Inquisition (Doubleday, £12.99). It vibrantly depicts life under the ruthless medieval Catholic church through the contrasting but linked stories of privileged Zarita and the beggar Saulo, whose family falls foul of Zarita's. The accounts of the Inquisition's methods are horrifyingly graphic – although probably, in fact, understated.

Winding forward nearly five centuries brings us to Annexed by Sharon Dogar (Andersen, £6.99). An imaginative, clever and compelling novel, it explores and extends the Anne Frank story from the point of view of Peter van Pels. Referred to in Anne's diary as Peter van Daan, he was the teenage boy with whom she enjoyed the beginnings of a romance while shut away in the secret attic with their families.

But not all teenagers are smitten with history. For many, fantasy wins every time, and there are some tasty new titles about for them. Take Yvonne Woon's Dead Beautiful (Usborne, £6.99). A first novel, it is narrated by a young Californian, Renée Winters, and is full of Gothic elements. For example, the discovery of her parents, dead in a wood; a sinister boarding school she is sent to, where there are strange customs and an ancient curriculum; plus a curse, and other dark secrets. Then she meets Dante Berlin, whose very name, with its connotations of hell and the romance of Europe, is an indication that all is not as it seems.

Divergent by Veronica Roth (Harper Collins, £9.99) is another debut novel, set in the US (but not as we know it), and the first in a trilogy. It depicts a world divided into five factions, each dedicated to the cultivation of a particular virtue – selflessness, bravery, intelligence, and so on – and on "choosing day", a 16-year-old such as Beatrice Prior has to opt permanently for a faction. Of course, as Beatrice soon realises, it's a flawed Utopia. Divergent owes something to novels such as Brave New World and William Nicholson's The Wind Singer, but it's otherwise fairly original stuff and the ending left me looking forward to the next instalment.

Melissa Marr's Darkest Mercy and Derek Landy's Mortal Coil (both HarperCollins, £6.99) are both parts of established series. Darkest Mercy concludes the Wicked Lovely pentalogy with the Summer King missing, the Dark Court bleeding, and a stranger walking the streets of Huntsdale. The style is engaging, but if you're not au fait with the rest of the series it isn't easy to unravel. If your teenager doesn't already know these books, recommend starting with the first instalment, Wicked Lovely.

Mortal Coil is a far lighter novel, very funny in places, and can be read independently of the previous four books in Landy's Skulduggery Pleasant series. It is set in Ireland – sort of – and Skulduggery is an engaging character, now reunited with his original head. I also enjoyed the feisty character of the sorceress, Valkyrie. Landy writes delightfully crisp, accurate prose, managing to be witty without any sense of dumbing down the language or pandering to teen-speak.

And so to modern, real-world fiction. Sandra Glover's Fallout (Andersen, £6.99) is about the long-term aftermath of an impromptu party held at Hannah's house when she was 16 and her parents were away. It details the inevitable house-trashing, linked to drugs, sex and teenage gang factions. But the interesting thing about this thoughtful novel – a salutary and very plausible tale – is the way the effects of the party follow Hannah for years afterwards, even while she's at university.

Equally gripping and realistic is Everybody Jam, an outstandingly strong first novel by Ali Lewis (Andersen, £6.99), set in the Australian outback. Danny lives on a cattle station and it's muster time. He wants to show that he's as good as his elder brother, Jonny, whom no one talks about since he was killed in an accident the year before. Add to the mix a 14-year-old pregnant sister, a mother who can't cope, and an English gap year backpacker hired to help out, and we're in the arena of sibling rivalry, family relationships and growing up, against a backdrop of drought, dust, devastating heat and the grittiness of Australian outback life. It is moving and enjoyable, and if historical novels teach history effortlessly, then Everybody Jam is one to do the same for geography.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments