Books of the month: From Marian Keyes’s ‘Grown Ups’ to Anne Enright’s ‘The Actress’

Martin Chilton reviews six of February’s releases for our monthly book column

Family traumas and secrets are a source of constant inspiration for novelists and February’s fiction includes new novels from Anne Enright, Marian Keyes, Hannah Rothschild and Cho Nam-Joo all featuring fractured, unhappy households.

Rothschild’s engaging tale House of Trelawney (Bloomsbury) cleverly satirises an unconventional aristocratic clan who have run into money troubles, while Keyes’s Grown Ups (Michael Joseph) is a sharp-eyed account of an unravelling family called the Caseys.

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 (Scribner), written by former South Korean television scriptwriter Cho Nam-Joo, sold a million copies in Asia and is credited with igniting the #MeToo movement in Japan. In the novel, translated by Jamie Chang, Nam-Joo blends fiction and reportage to tell the backstory of a 33-year-old woman having a nervous breakdown – and the misogyny that helped cause her problems.

Kim’s family only notice things are going wrong when she starts making social blunders by comically imitating people close mito her. This witty, disturbing book deals with sexism, mental health issues and the hypocrisy of a country where young women are “popping caffeine pills and turning jaundiced” as they slave away in factories helping to fund higher education for male siblings. Even if a bright woman does land a job in business, she finds the ceiling is made of reinforced glass. “Companies find smart women taxing,” narrator Kim Jiyoung is told.

Enright is one of three former Booker Prize winners with new novels out this month. The Dublin author’s The Actress (Penguin) is the superb tale of a daughter’s search for the truth about her Irish stage star mother. Graham Swift’s Here We Are (Simon & Schuster) also shows how ambition affects close personal relationships. Swift’s story, mainly set in Brighton in 1959, is based around a love triangle involving an end-of-pier magician, his female assistant and the charismatic compère who is headed for stardom. Here We Are is a subtle portrait of a vanished world, with moving passages about the problems of wartime evacuees returning to impoverished London life after the wonders of the countryside.

Aravind Adiga, who won the Booker for The White Tiger in 2008, sets Amnesty (Picador) in Australia. The Indo-Australian author has pertinent things to say about moral dilemma in the story of a Sri Lankan immigrant who is living as an illegal in Sydney. If he does the right thing, he risks being deported.

Three of the best new novels – Colum McCann’s Apeirogon, Tan Nahisi Coates’s The Water Dancer and Jenny Offill’s Weather – share the distinction of turning the horror of real life into masterful, empathetic fiction. All three are reviewed in full below.

Among the other fiction highlights are Strange Hotel by Eimear McBride (Faber), the story of a nameless woman returning to a series of nondescript hotel rooms and the haunting memories her trip revives. Strange Hotel is painfully sad, but laced with tender humour. A Small Revolution in Germany by Philip Hensher (4th Estate) is a poignant, melancholic story about the disillusionment of growing up.

Two fine examples of historical fiction are The Foundling by Stacey Halls (Manilla Press) and The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave (Picador). The Foundling, which is set in the Bloomsbury hospital for orphans in Georgian times, centres around the mystery of what happens when a woman returns to reclaim her illegitimate child. It’s a moving, atmospheric chiller. The Mercies is a gripping tale of love and obsession, inspired by the real events of a storm on the Norwegian island of Vardø in 1617 that prompted witch trials. Absalom Cornet, the man used to bring the women to submission, is a creepy creation by Hargrave, in her debut adult novel.

Another excellent debut is Kingdomtide by Rye Curtis (4th Estate), which is the story of Cloris Waldrip, a 72-year-old Texas woman lost in the Montana mountains after a plane crash that kills her husband and the pilot. The similes are gritty (“flies throned the tongue in his gaping mouth like little green potbellied despots”) in a deeply meditative novel about grief, regret and enduring love. Talking of debuts, Nightingale by Marina Kemp (4th Estate), in which a young woman leaves Paris for the provinces to work as a live-in nurse for a tyrannical old man, is also impressive.

Closer to home is the sharp, clever debut thriller Firewatching by Russ Thomas (Simon & Schuster), which is set in Sheffield. Detective Adam Tyler is hunting a serial arsonist in the first in a new police procedural series. Michelle Gallen’s Big Girl Small Town (John Murray) is a darkly comic tale set in Northern Ireland, about a JR Ewing and Dallas-obsessed girl called Majella.

The final recommended debut is The Book of Echoes by Rosanna Amaka (Doubleday), set in Nigeria and London, and across different centuries, narrated by the spirit of a slave woman. Amaka has written a powerfully redemptive story about the resilience of love in the face of racism.

There are some cracking thrillers, including Klaus-Peter Wolf’s The Oath (Zaffre). AD Miller’s Independence Square (Harville Secker) is a timely story about corruption, based around a British diplomat in Kiev caught in a lurid scandal. It’s a taut, twisty treat. The reliably good James Oswald goes ever darker in Bury Them Deep (Wildfire), the latest in the Inspector McLean series. It’s a mystery about a woman who goes missing in remote woodlands that were once associated with the cannibal Sawney Bean. What happens when human meat becomes legal is the basis for Agustina Bazterrica’s Tender is the Flesh (Pushkin Press), a compelling dystopian novel that won the Premio Clarín Novela, Argentina’s most prestigious literary prize.

For non-fiction fans, there are heavyweight biographies of Dave Brubeck and the Dalai Lama. There will also be a media frenzy around John Bercow, the shy and retiring former Speaker of the House. Who better for publishers Orion to have onboard to promote Unspeakable: The Autobiography than a man whose catchphrase is “order, order”?

I loved The Lost Pianos Of Siberia, Sophy Roberts’s joyful, eccentric journey through one of the world’s wildest places. It’s a dismal reality that a book such as How to Argue with a Racist: History Science, Race and Reality (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) even has to exist. Author Adam Rutherford challenges the bogus ways that Neo-Nazis are co-opting genetics to justify bigotry. Who knew, for example, that far-right fanatics film themselves “chugging milk” with their shirts off? It’s done to prove they can process lactose in a way they believe demonstrates an assertion of their udder racial superiority.

Milk chugging wasn’t the only curious fact that came out of this month’s new books. I learned that during the Prussian Siege of Paris in the 19th century, the starving French population ate “salamis of rats”. That’s just one of the tasty morsels in historian Annie Gray’s enjoyable Victory in the Kitchen: The Life of Churchill’s Cook (Profile Books). Even with rationing in force, Winston Churchill was fed well by his personal cook Georgina Landemare. The prime minister looked after her in return, always hustling her first into the bomb shelter. “If Mr Hitler gets you, I won’t get my soup,” he told her. As well as soup, Churchill also liked to drink whisky and soda with his breakfast, describing it as his “mouthwash”.

Finally, given the impending climate crisis, it is no surprise that the future of the planet and natural world are the subject matter of several new publications. Chris Goodall’s What We Need to Do Now for a Zero Carbon Future (Profile Books) looks at the measures governments need to implement to tackle climate change, and he also offers practical solutions for ordinary citizens – such as buying second-hand clothes and cutting down on red meat.

Perhaps the most uplifting book of the month, however, is the marvellous Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild (Allen Lane) by Lucy Jones. Her eloquent book ruminates on why it is essential for us all to experience nature in an era of rapidly increasing urbanisation.

Jones blends sensitive personal tales with interviews and thought-provoking evidence to back up her engrossing arguments about the benefits of nature. The section on “forest-bathing” in Japan lingers in your mind. Jones explains why walking in forests or woodlands reduces stress. The chemicals emitted by trees and plants lower negative feelings and help with feelings of anxiety and fatigue. Discover Losing Eden – it is a vital book for our modern times.

In the latest of our “books of the month” column, we have extended reviews of six books published in February 2020.

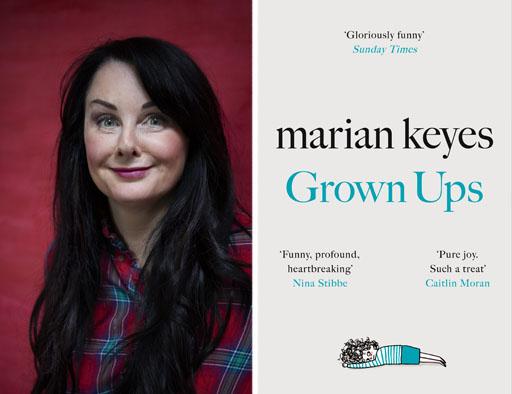

Grown Ups by Marian Keyes ★★★★☆

Marian Keyes has won a legion of fans for the way she wittily dissects domestic life and they will not be disappointed by Grown Ups. The family dysfunction in her new novel is based around marriages involving three brothers: Johnny Casey (to Jessie), Ed (to Cara) and Liam (to Nell).

Although the book is set in the digital age of Fortnite, Airbnb and family WhatsApp groups, it is the age-old problems of deception and fear of betrayal that come to haunt this “glamorous” Dublin family. An action-packed prologue sets the ball rolling, and it’s not even too much vino that causes beans to be spilled. After suffering a blow to the head, Cara (“in concussus veritas”, presumably) reveals secrets that scheming in-laws would rather remain hidden. Over the following 630 pages, Keyes peels away at marriages on the skids.

There’s a lot of flawed masculinity in Grown Ups. Men “act the arse” because their wives’ careers are going well, others are “on the constant lookout for sex, like a racoon around a bin”. Liam is skewered by Keyes as an example of the modern predatory male. The book also introduced this delicate flower to the image of the male “curtain wiper”, but you’ll have to read the book to find about that particular grossness. In one wince-inducing scene, Keyes captures what it’s like for a woman to get a massage from a repellent man.

Amid the family carnage, which takes place in Mayo, Tuscany and Dublin, Keyes sensitively examines the damage an image-obsessed culture wreaks, whether on teenage girls who are left feeling “uncool and wrong” or in middle-aged women with eating disorders. Cara, Jessie and Nell are all vulnerable in different ways. In one of the main plotlines, Cara endures monumental “self-loathing”, because of her binge-eating and bulimia. “I barely know any woman who has a normal relationship with food or her body,” she says.

Grown Ups contains astute observations about disintegrating relationships and Keyes is amusing about the ordeals involved in hideous family gatherings. The “s***-show” murder-mystery weekend the Casey clan face at Gulban Manor is particularly enjoyable. But then, compulsory sociability is never a good idea. “It will be relaxing,” says Jessie, as she organises another Casey family do. “The beatings will continue until morale improves, right?”

Grown Ups by Marian Keyes is published by Michael Joseph on 6 February, £20

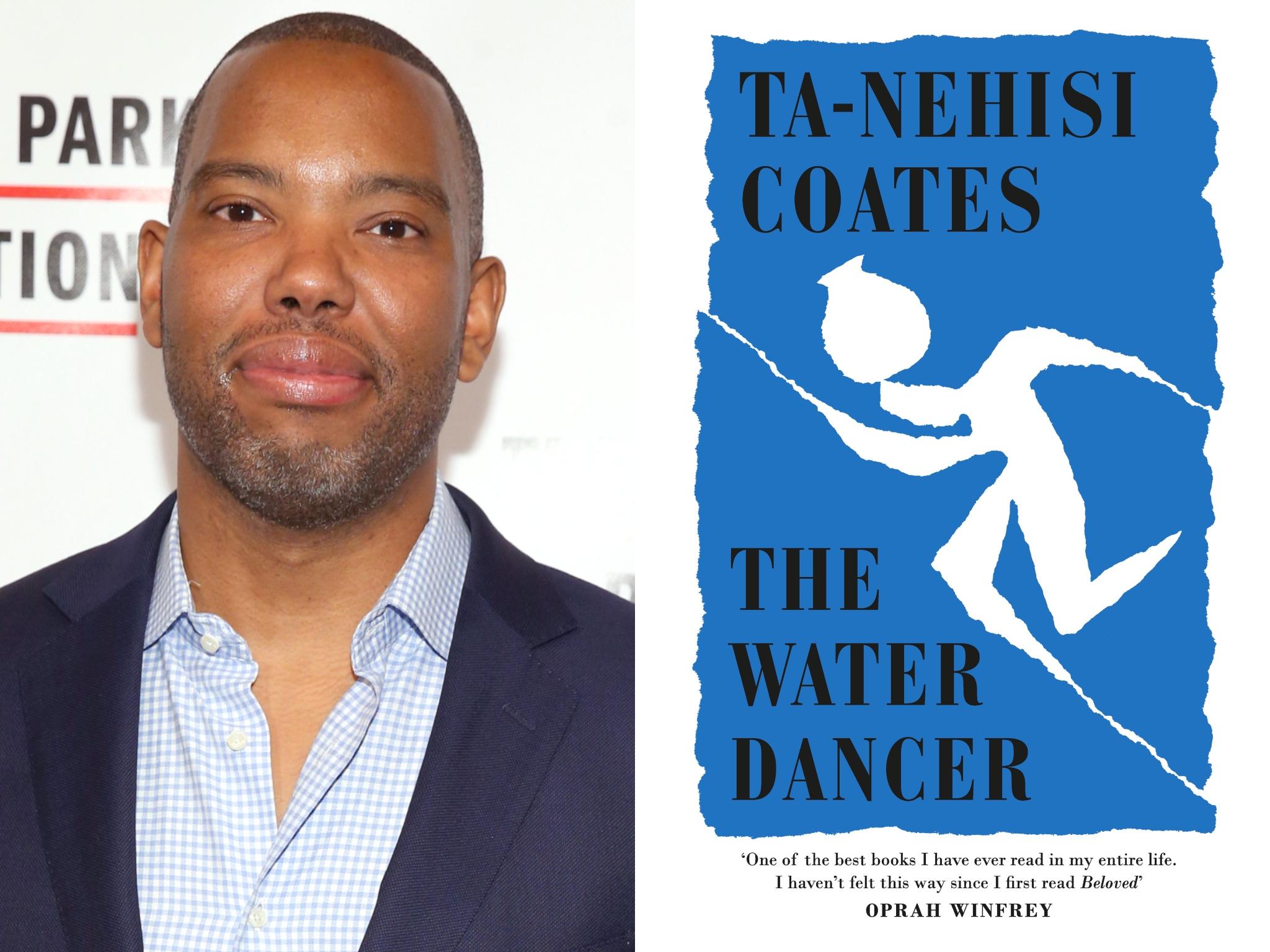

The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates ★★★★☆

Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me won the National Book Award for Nonfiction in 2015 and The Water Dancer is his debut fiction work. The narrator is an inter-racial Virginian slave called Hiram Walker. Early on, we discover he has a photographic memory and his father, a tobacco plantation owner, gets him to perform memory tricks to entertain his friends. One thing he cannot remember, though, is his mother, who was sold off by his father when he was only nine.

The Water Dancer reveals Walker’s story of escape, as he remembers his mother and learns to use the paranormal powers he has inherited. Coates uses the metaphor of conduction by water to explain how the protagonist can disappear from one place and jump location across water to appear in another – sometimes with fellow slaves in tow. This mystical power of “conduction” makes him a highly prized asset to the underground railroad. During his work freeing slaves, he meets real-world figures such as Harriet Tubman and William Still.

Given the misery of life for slaves, it is no wonder that the experience of escape must have felt magical to those lucky enough to get away. However, the magical realism in the novel is less affecting than the parts more grounded in reality. Coates did an incredible amount of research for a novel that investigates the psychological effects of slavery, on both jailers and captives.

It is hard to even imagine the sheer agony of having to watch one’s children or parents sold off for profit, and then having to struggle through a life of backbreaking misery. The precariousness of a slave’s life is made heartbreakingly clear in the novel through an offhand reference to a man being shot for using the wrong hoe. Coates’s slave characters are complex human beings, who understand the mindset of their owners. “We really ain’t nothing but jewellery to them,” says Walker’s lover Sophia.

The Water Dancer is a damning portrait of slothful oppressors whose actions are covered by a thin veil of dignity. “Bored whites were barbarian whites,” reflects the guarded, cautious narrator Walker. The book uses euphemisms, so the slaves (the Tasked) know only too well that “the masks of breeding” of the slave owners (the Quality) can quickly fall away. This is especially true at a time when the great houses of slavery in Virginia, including the Lockless Estate owned by Walker’s father, are beginning to collapse.

It is not just the world of the Deep South that is “built on a foundation of lies”, however. There is hypocrisy at work in the opulent, slave-free northern cities. One haunting section is set in Philadelphia’s Washington Square. This affluent area was built on top of the pits where hundreds of black corpses were dumped after having been deliberately exposed to an infection running rampant in the city (it was thought they could suck up the fetid air and hold it captive in their bodies). “Here in the free North, the luxuries of this world were built right on top of us,” says the narrator.

Coates has written an ambitious, lyrical novel (one old slave’s eyes are described as having “the pooling of sadness”), and his mesmerisingly vivid descriptions bring to life the “unending night” of that time.

The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates is published by Hamish Hamilton on 6 February, £16.99

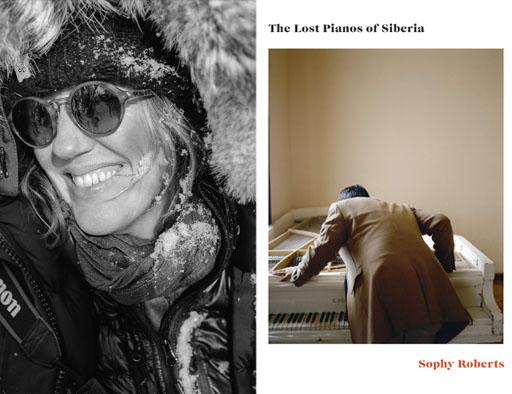

The Lost Pianos of Siberia by Sophy Roberts ★★★★★

Sophy Roberts is an intrepid travel writer, not least for facing the “vicious” mosquitoes of northern Asia – which local legend has it were born from the ashes of a cannibal – in her marvellous account of searching for Siberia’s lost pianos.

Asked to summon a picture of Siberia, most of us might imagine what Fyodor Dostoevsky called “a house of the living dead”, a frozen land of misery that was home to the 19th-century convicts banished by tsars and later to Stalin’s Gulags, the forced-labour camps in which so many political dissidents died in despair.

However, even in the days before modern transport, music found its way to one of the most remote places on earth. In the 19th century, hundreds of pianos were taken on trains and dragged across snow to far-flung regions. Roberts tracks these musical instruments, their origins and where they ended up – and in the process tells the riveting history of a country that covers an eleventh of the world’s land mass. Siberia, she notes, is being hit hard by climate change and the northern permafrost is melting at an alarming rate.

The devil is in the detail, large and small. One moment Roberts is visiting the site of the murder of the Romanov royals (it took 20 minutes to stab and shoot them to death in Ekaterinburg, because they were wearing diamond-filled corsets that acted “like bulletproof vests”), the next she is discovering a small town where Duke Ellington’s records were imported in the 1930s. The book is crammed with the bizarre and the disconcerting, including a section about the grisly human experiments conducted by the Japanese in Harbin.

The chapter on Sakhalin Island alone is brilliant. Prisoners were chained permanently to their wheelbarrows – even while they slept. There is a startling photograph of these poor souls, one of a host of images in the book that make you tip your hat to the brilliant picture researchers and the work of photographer Michael Turek, who also made a short film documenting Roberts’s quests.

Siberia certainly holds “some of the bleakest stories of human cruelty”, as Roberts remarks, but it is also a wellspring of culture and humanity. You see all sides of the picture in this masterful example of modern historical travel writing.

The Lost Pianos of Siberia by Sophy Roberts is published by Doubleday on 6 February, £16.99

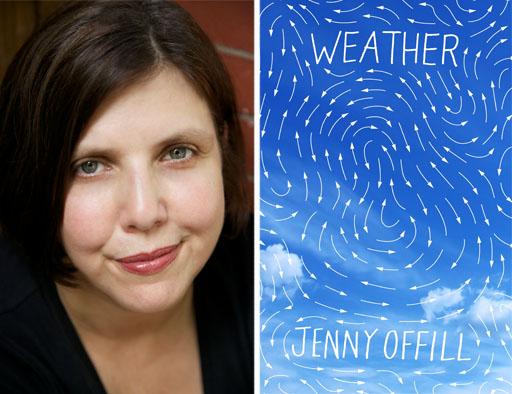

Weather by Jenny Offil ★★★★★

It’s never a wise idea to stay up late at night “googling prepper things”, unless you have the skills of Robin Hood, of course. A lot of doomsday prepping advice seems to involve stockpiling crossbows along with water filter systems.

The troubled inner monologue of librarian Lizzie Benson is the subject of Jenny Offill’s superb fictional work Weather. Lizzie has become obsessed with “Disaster Psychology” and her narrative, told in hundreds of bite-sized snippets, reflects her fragmented musings on everything from television shows about extreme couponers and her admiration for novelist Jean Rhys to the best place to build a doomstead for hunkering down after a global disaster.

Lizzie is overflowing with anxieties about a world that is becoming “more fragmented and bewildering”. Accepting a job from an old mentor called Sylvia Liller to answer questions from fans of the end-of-the-world podcast Hell and High Water only heightens her disquiet about the state of the world. Lizzie ponders on which neighbours you can trust in a “culture of denunciation”. Trump, though unnamed in the novel, lurks in the pages like the smell of a rotting animal. Asked by a fan of Hell and High Water about the best ways to prepare children for the coming chaos, Lizzie answers that sewing and building skills may take second place to “techniques for calming a fearful mind”.

The book is a treasure trove of oddities. Experts are cited, anecdotes and jokes are told. Offill even offers valuable survivor tips, such as the instructions for how make a candle out of a tin of tuna. Weather is not a window into a happy world. Everyone goes around with their heads down these days, says Sylvia. The reliance on social media is not the answer. Lizzie says it makes her feel “like a rat who can’t stop pushing a lever”.

There are lighter moments, too, as Lizzie reflects on the weird patrons of the library, the state of her marriage to Henry, her concerns for her son Eli and her “enmeshment” with her recovering drug addict brother Ben. The book achieves a tricky balancing act: it is oddly captivating with its amusing gallows humour about crazy doomers, and at the same time is also a deeply disturbing commentary about a thoughtful woman having an understandable existential crisis.

As long ago as 1711, the theologian/philosopher William Derham lamented the human urge to “ransack the world”. “Hasn’t the world always been going to hell in a handbasket?” Lizzie asks Sylvia. “Parts of the world, yes, but not the entire world,” she replies. Offill’s book is a fitting fictional dance macabre for our spiralling existence.

Weather by Jenny Offill is published by Granta Books on 13 February, £12.99

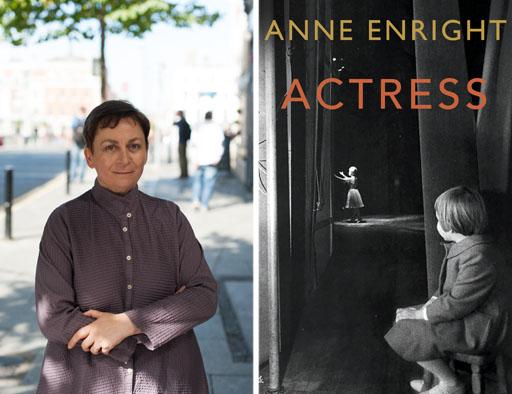

The Actress by Anne Enright ★★★★★

Anne Enright’s The Actress is a beautiful, psychologically masterful novel about a complex mother/daughter relationship. The mother is Hollywood star Katherine O’Dell; the daughter is a marginally successful author called Norah, who is trying to make sense of the “merry-go-round” upbringing she survived.

Being the daughter of Katherine wasn’t easy as a child. When Norah was about seven, a boy pushed her at a party. “My mother, in full make-up and with her taffeta skirt swaying behind her, bent down to hiss ‘if you touch my daughter again I will bite you.’” Narrator Norah is now 58, the same age at which her mother died, and is seeking answers to some of the mysteries of her past, not least the truth about the identity of her father, “the ghost in my blood”.

Norah begins to understand more about her mother’s lonely life and what a desperate battle she fought to remain successful while putting on “a damn fine show” of seeming to be happy. This fakery began early. “The most Irish actress in the world” was not even Irish. She was born in London. She was always at the mercy of predatory men. As Katherine’s story unfolds, you understand why she often felt like she was being “eaten alive”. Her story ends in madness and despair, with a crazed act of violence.

The Actress is a superb example of why fiction still matters in the 21st century. It’s funny, perceptive and full of pathos. Katherine’s early days with a troupe of touring actors are amusing (“Oh, give her a good shake!,” a woman in the audience in Ballyshannon shouts out when Romeo discovers Juliet in the tomb), before the dismal realities of life as a film star take hold.

“Hollywood was a brothel,” says Katherine. Real-life actors make fleeting appearances in the novel. The affectatious Orson Welles is a “pig”, his face “as big as a serving platter”. Enright has fun with an era when people “drank champagne from a shoe still warm from human foot”. She also dissects the later bohemian theatre world of Dublin in the 1970s, a time of big-bellied men “pregnant with porter”. The shootings, reprisals, raids and bombings in Ireland at the time are a sinister backdrop in these moments.

The inner dialogue and life story of Norah is compelling and she is a charming, sympathetic and shrewd guide to her mother’s decline. Their shared history of facing manipulative, predatory men – including the absurd “Duggan The F***er” – is achingly sad. Horrific experiences of sexual assault haunt both mother and daughter.

Norah remains a defiantly warm-hearted guide to her mother’s descent into madness. For all Katherine’s flaws and faults, it’s hard not to feel that the people with “horrible little hearts” are the real monsters of this wonderful novel.

The Actress by Anne Enright is published by Jonathan Cape on 20 February, £16.99

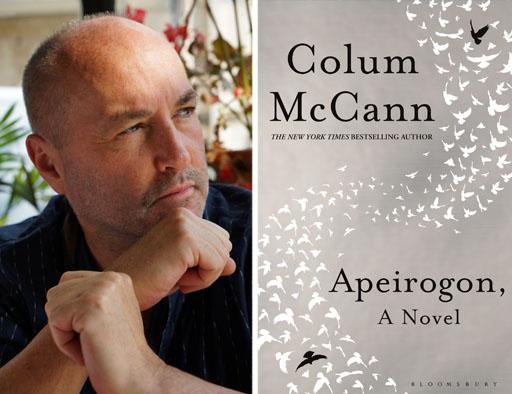

Apeirogon by Colum McCann ★★★★★

An apeirogon is a shape with a countably infinite number of sides – and Colum McCann’s transcendent book is full of hundreds of thought-provoking, emotional segments. It’s fact-based fiction telling the story of the unlikely friendship between Israeli Rami Elhanan and Palestinian Bassam Aramin.

Rami’s grief is Bassam’s grief. Both have lost their daughters to soul-destroying violence. In 1997, “life burst into a million pieces” for Rami when his 13-year-old daughter was blown to bits by a suicide bomber (tellingly, the people who clean up human remains prefer to describe the killers as wearing “homicide vests”). McCann deftly depicts the lacerating moment when Rami has to tell his 80-year-old father that his beloved granddaughter has been murdered.

A decade later, Bassam’s 10-year-old daughter Abir was shot in the head with a rubber bullet, fired by an unnamed 18-year-old border guard during a school break, just after Abir had bought candy from a grocery store. Doctors cannot save Abir. Their equipment is failing. “It was the sort of hospital that needed its own hospital,” McCann notes. In 2010, a judge in the civil case brought by Abir’s family ruled that the killing was “unjustified”. Rubber bullets are called “Lazarus pills” by the Israeli soldiers, McCann notes sardonically, because when possible “they could be picked up and used again”.

McCann turns these haunting true stories into engrossing fiction, and he does so with poetic power. “The days hardened like loaves: he ate them without appetite,” he writes of Bassam, who spent seven years in jail as a youngster for planning an attack on Israeli troops. There is a moving section about the peace Bassam finds for a spell after relocating to Bradford, partly through the simple pleasures of gardening. It’s a long way from Gaza, where bombing operations into the West Bank are often referred to by Israeli officials as “mowing the lawn”.

The dangerous, suffocating atmosphere of the West Bank is made clear in a wonderful simile. McCann describes an amble through a 10-acre environmental centre as “like walking the rim of a tightening lung”. Life in Jerusalem is lived under a “hot murdering sun”. Corruption is endemic, the constant bribery “a slow strangulation”.

Both bereaved fathers gradually decide they will use the force of their grief as a weapon. “In the end despair is not a plan of action,” says Rami. “It’s a Sisyphean task to create any sort of hope.” As they work together for The Forgiveness Project, trying to unite the divided communities by working with victims for all sides, both face accusations of being “contaminated”, of “sleeping with the enemy”.

McCann stitches together reflections on history, the nature of friendship, politics, the conflicting power of hatred and forgiveness, wildlife and art – turning them into a gorgeous tapestry. Apeirogon is told through a multitude of stories – one thousand in all, of varying lengths, split by real transcripts from the two fathers in the middle of the novel – that spin-off at bizarre tangents. Among the digressions are about Francois Mitterrand’s love of eating tiny birds, and the strange story of Mossad “honeypot” agent Cheryl Hanin Bentov, who ended up selling real estate in Florida.

Apeirogon is a tough read. The description of Salwa waiting at the hospital for the ambulance to bring her injured daughter Abir, a desperate mother’s heart leaping each time the doors open, is excruciating. But pain is part of what makes this book a masterpiece – an essential hymn to peace and forgiveness.

Apeirogon by Colum McCann is published by Bloomsbury on 26 February, £18.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments