My forefather's life in Manchester's slums: Discovering family roots in the 'hell on earth' of Angel Meadow

Of all the terrible slums created by the Industrial Revolution, Angel Meadow in Manchester was the worst – a violent Dickensian nightmare ridden with crime and disease that even Friedrich Engels called 'hell on earth'. One of the residents was the great-great-great-grandfather of 'Independent' writer Dean Kirby, who tells his story here

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Walk through almost any car park between the futuristic office blocks in Manchester city centre and you are stepping on a thin crust of concrete that separates you from a lost underworld. Down there beneath your feet lie the carcasses of Victorian houses that were demolished and swept away in post-war slum clearances, as Manchester rose again from the ashes of the Blitz. Only their cellars and foundations remain, sealed shut like tombs and miraculously untouched by the new city of steel and glass erected round them.

On an overcast February morning in 2012, archaeologists searching for evidence of Manchester's 19th-century slums peeled open the concrete lid of one of these car parks and made a startling discovery – the home of my Victorian forefather. Born in 1831, in County Mayo on the rugged west coast of Ireland, William Kirby – my three-times great-grandfather – was a farm labourer who fled to Manchester after surviving the potato famine, and washed up in Angel Meadow, the city's most savage slum.

When Manchester was the powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution, this violent and disease-ridden area of just 33 squalid acres was home to 30,000 workers, many of them Irish immigrants, who struggled for survival in a condition so brutalising that it was described by Karl Marx's patron Friedrich Engels as "hell upon earth".

One hundred and seventy years later, old maps and rent records had already helped me to pinpoint where William's two-storey home would have stood: it was one of four buildings unearthed by a team from Oxford Archaeology North ahead of work to build a new headquarters for The Co-operative Society at the northern edge of the city. And they allowed me and my father, John Kirby, to clamber down a shaky ladder and touch the still-sooty bricks of William's fireplace and the walls – just half a brick thick – that separated his 10ft-square, one-up-one-down from the house next door.

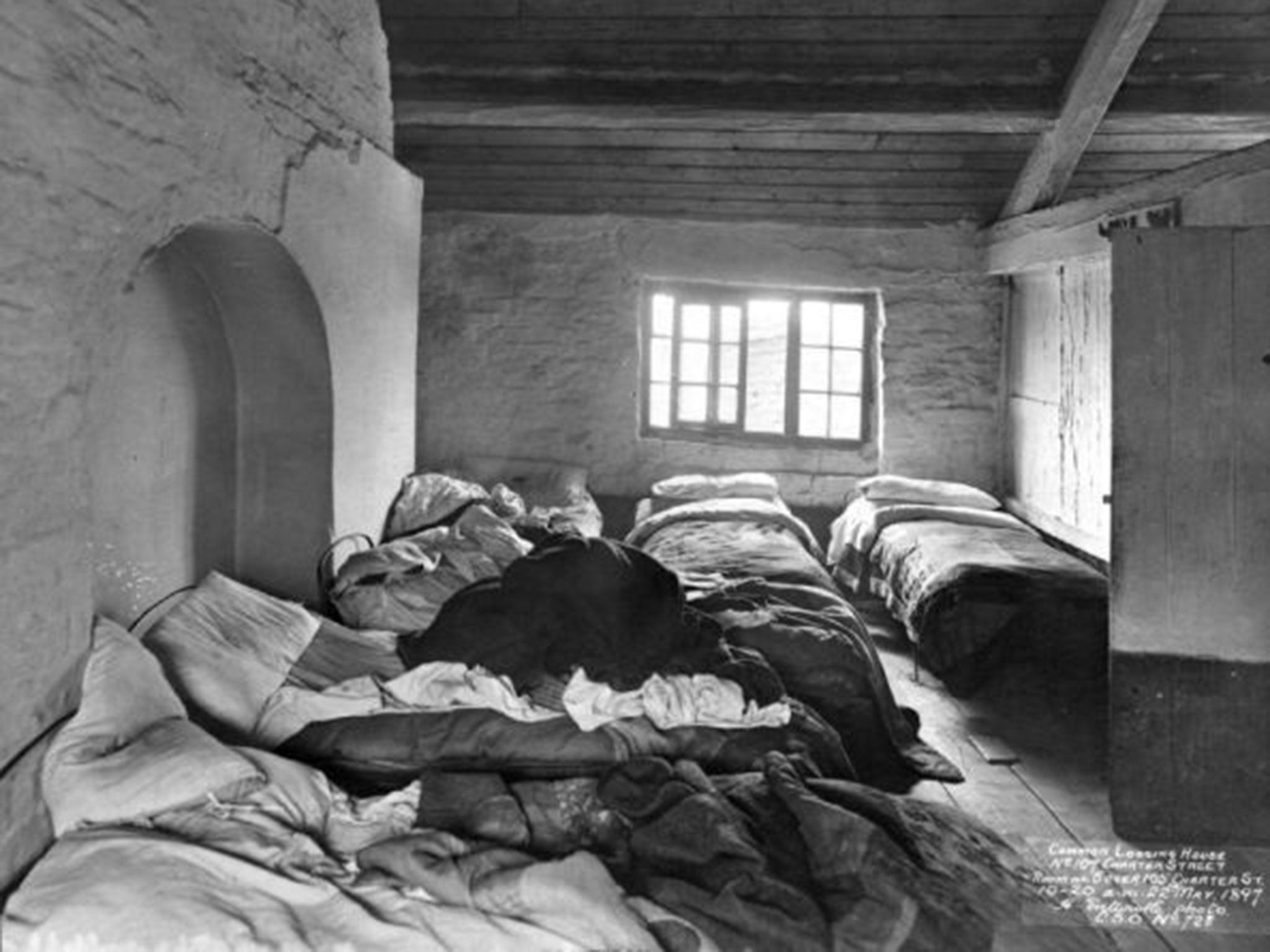

The archaeologists had unearthed metal hinges, fragments of wooden doorframes, clay pipes and even a door key. They also showed us the privy, in an alley, that William and his family would have shared with 100 other people. And these remarkable discoveries set me on a journey to find out more about William's life in Angel Meadow, the ironically named slum that Manchester would prefer to forget. As I began to trawl the city's archives over the coming weeks and months, I started to drift off to Angel Meadow in my imagination. I descended into damp cellars in search of William, stumbled through backyard pigsties and came face-to-face with the scarred and tattooed street fighters, or "scuttlers", in the slum's smoke-filled beer houses. I crept into the dingy lodging houses where new arrivals had to sleep naked with strangers because it was the only way of keeping their clothes free of lice. And the more I read, the more astonished I became by my ancestor's survival in this hellish place – leading to my own existence more than a century later in the city that his blood, sweat and tears had helped to create.

Victorian Manchester was the marvel of its age – celebrated for its ingenuity, guts and swagger. Its tycoons made astonishing fortunes as they built "Cottonopolis", and their wares were shipped to distant shores across the British Empire. But around a gilded centre with a stock exchange, banks, mercantile chambers and shops lay a rain-soaked city of mills, warehouses, furnaces and chimney stacks; stinking, noisy and dangerous for the 300,000 souls who fed its machines. It was a Jekyll and Hyde city of blinding wealth and binding poverty.

The French philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville explained to Parisians in 1832 that Manchester was a "watery land of palaces and hovels", where "pure gold flowed from a raw sewer" and where civilised man was "turned back almost into a savage". He continued: "A sort of black smoke covers the city. Under this half-daylight, 300,000 human beings are ceaselessly at work. A thousand noises disturb this damp, dark labyrinth, but they are not the ordinary sounds one hears in great cities." Another visitor, the German author Johanna Schopenhauer, said that Manchester resembled a huge forge or workshop, permanently dark and smoky: "Work, profit and greed seem to be the only thoughts here. The clatter of the mills and the looms can be heard everywhere."

The city's slums formed what one "Ragged School teacher" described as a "dark tide of misery and wretchedness". These were places where the sun, a rare sight in Manchester even today, could only penetrate when it was directly overhead. And Angel Meadow was the worst slum of them all – a warren of streets bounded by the coal-black River Irk, which was covered with pools of green slime and bubbled with miasmatic gases. It was said that from a bridge 50ft above, the stench was unendurable.

Angel Meadow was crammed with lodging houses, pubs and marine stores, or "putty shops", where thieves fenced stolen goods. Backyard slaughter houses, breweries, a gasworks, boneyards, catgut factories and piles of dung tainted the air with a cocktail of aromas. In narrow back alleys stood privies with urine-soaked floors and ash-pits overflowing with rotten vegetables. New arrivals found themselves in a strange and disorderly world governed by pickpockets and tramps, where "tommy shops" sold pea soup at a penny a pint and druggists gave laudanum to mothers to quiet their crying babies. Beer houses with names such as the Flying Ass and the Dog and Duck were dens for gangs of robbers and confidence tricksters with glorious names such as Jemmie the Crawler and Cabbage Ann. And these places, one Victorian observer wrote, were the rendezvous of the elder thieves, the fighting men, the swindlers and mutilated beggars.

Angel Meadow was said to be a place where "beggars grew fat". (A sketch found by police in one of the lodging houses pinpointed the best begging grounds in the city.) Prostitutes also worked the slum's streets, and "rescue workers" estimated that only a quarter of the houses in Charter Street, where William Kirby lived, were free of vice.

Like the East End of London and the Five Points in New York, Angel Meadow's reputation was born in its lodging houses, airless cellars and back alleys – but the narrow streets were more terrifying, filthier and deadlier than the worst of their rookeries. The death rate in Whitechapel for 1888 – the year Jack the Ripper was stalking the streets – was 21.8 per 1,000 people. In Angel Meadow, it was 31.9, the worst in England. Missionaries from London were appalled when they travelled here. Half of those who died in the slum were children under five – many of them lying as still as dolls and slipping away as laudanum seeped through their veins.

Only the brave, the stupid and the helpless entered – among them journalists, Ragged School teachers, priests and doctors, who risked being attacked as they attempted to highlight the conditions. (The lucky ones escaped only with having their hats dislodged by the slum's favoured missile – a dead cat.) The brave included Engels, who toured the deepest realms of the inferno as he researched his provocative book, The Condition of the Working Class in England, in 1844.

Engels, who had been sent to Manchester to work in his family's mill, wandered beneath the slum's railway viaduct and through a web of washing lines to enter "a chaos of one-roomed huts" where he was watched in silence by the inhabitants, leaning heavily against their doors. To him, they were a "physically degenerate race, robbed of all humanity", their homes were nothing more than "cattle sheds for human beings", and he wrote: "If anyone wishes to see in how little space a human being can move, how little air – and such air – he can breathe, how little civilisation he may share and yet live, it is only necessary to travel hither."

A Scottish journalist, Angus Bethune Reach, also descended into one of the slum's cellars, to find a man sleeping on the floor next to a half-grown calf, along with a pensioner lying in a coffin-sized cave, a burrow scooped out through the wall into the bare earth. Sanitary inspectors armed with alcohol and strong tobacco – to fend off the noxious smells – discovered a donkey in another cellar; as well as trapdoors to illicit distilleries, which produced illegal liquor or "poteen" at the highest strength.

Efforts to close these fever-breeding cellars in the 1860s were hampered by the fact that many of them were owned by city councillors, who stood firm against attempts to close them, claiming it would leave the workhouse overburdened. And indeed they were only defending the status quo. For Angel Meadow, which had once been a rural pasture on the edge of town, had begun its descent 80 years before, when Richard Arkwright opened the world's first steam-powered cotton mill on the Irk, which soon had more mills along its banks than any other river of the same length in England.

But the real death knell for Angel Meadow had been the siting of a paupers' cemetery next to the nearby St Michael's Church in 1787. Just 30 years later, it was crammed full with the bodies of an estimated 40,000 paupers. Joseph Aston, who produced the first guidebook to Manchester in 1816, called it a "depot for the dead", writing: "A very large pit is dug and covered with planks, which are locked down in the night, until the hole is filled up with coffins piled beside and upon one another."

The next year, it was closed to new burials. Its walls collapsed due to misuse, and the few headstones were stolen to fill holes in the walls and floors of surrounding houses. Slum-dwellers began to use the cemetery as a dumping ground for ashes, offal and rotten shellfish. Children played in piles of straw tipped from fever beds – or set it on fire – and played football with the skulls that would emerge from the uneven ground. Body snatchers crept into the cemetery at night and dug up bones, to sell to Manchester's glue factories. And the cemetery became the scene of weekly fights – including one notorious battle between two one-armed tramps, which ended when one reportedly bit off the other's only hand. The victor, named Stumpy, was then beaten to a pulp by the watching crowd for breaking the slum's fighting code and banished to another part of Manchester, where it was said his mangled face told its own story.

A journalist from The Manchester Guardian was shocked by the extent of the violence that permeated the grubby streets when he visited in 1870. "It is all free fighting here," he wrote, "Even some of the windows do not open, so it is useless to cry for help. Dampness and misery, violence and wrong, have left their handwriting in perfectly legible characters on the walls." Not least by the scuttlers. These tribes of young street fighters patrolled the streets in tight-fitting punchers' caps and flared trousers, attacking rival gangs with knives and belt buckles – the most feared of them being the 5ft-tall steel-eyed Henry Burgess, whose weapon of choice was an iron poker. In the hot summer of 1893, he turned a rival named Thomas Matthews into a human fireball after attacking him with a paraffin lantern.

An anonymous writer who dubbed himself "The Scout" wrote of the slum in the year of Matthews' death: "When night falls I had rather enter an enemy's camp during the time of war than venture near such dens of infamy and wretchedness. But the poor live here." And died there. Only three of William Kirby's children survived to adulthood and a death certificate from 1877 shows his youngest, also called William, died from convulsions brought on by a fever in the very house discovered by the archaeologists. Three years later, his mother joined him. My ancestor, who could not write, signed his mark on the certificates in a shaky hand.

Conditions in the slum improved slightly in the years to come. Brave police officers, including one who lost an eye after it was kicked clean out by a thug wearing pointed, brass-tipped clogs, eventually defeated Angel Meadow's scuttling epidemic with the help of Ragged School missionaries who opened a gym and taught the thugs to read and write. Manchester Corporation shut down the lethal cellars and engineers began to demolish the worst houses and courts. They even laid flagstones over the old cemetery and turned it into a playground.

William somehow made it out of the slum. But housing officers who offered his neighbours a chance to leave Angel Meadow in the early 20th century were shocked to discover that many had become so accustomed to the conditions that they said they wanted to stay. Indeed, families continued to scrape an existence there until Nazi bombers did what city planners should have, and razed the slum. Only a few of the old houses remained, standing in the ruins like broken teeth; and streets once throbbing with life became empty backwaters. And now Angel Meadow has quietly become a sought-after area: the few remaining factories have been turned into luxury flats and the playground – still hiding thousands of bodies – has become an award-winning park. The area's two remaining pubs sell fine food and real ale, and the old railway viaduct now takes workers from their steel and glass office blocks to Manchester's suburbs in sleek, yellow trams.

William Kirby finally died from chronic bronchitis and exhaustion in the workhouse in 1902. I left the dig with a brick from his hearth. It was still covered in soot from the fire that had kept him warm.

'Angel Meadow: Victorian Britain's Most Savage Slum' by Dean Kirby (£14.99, Pen & Sword) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments