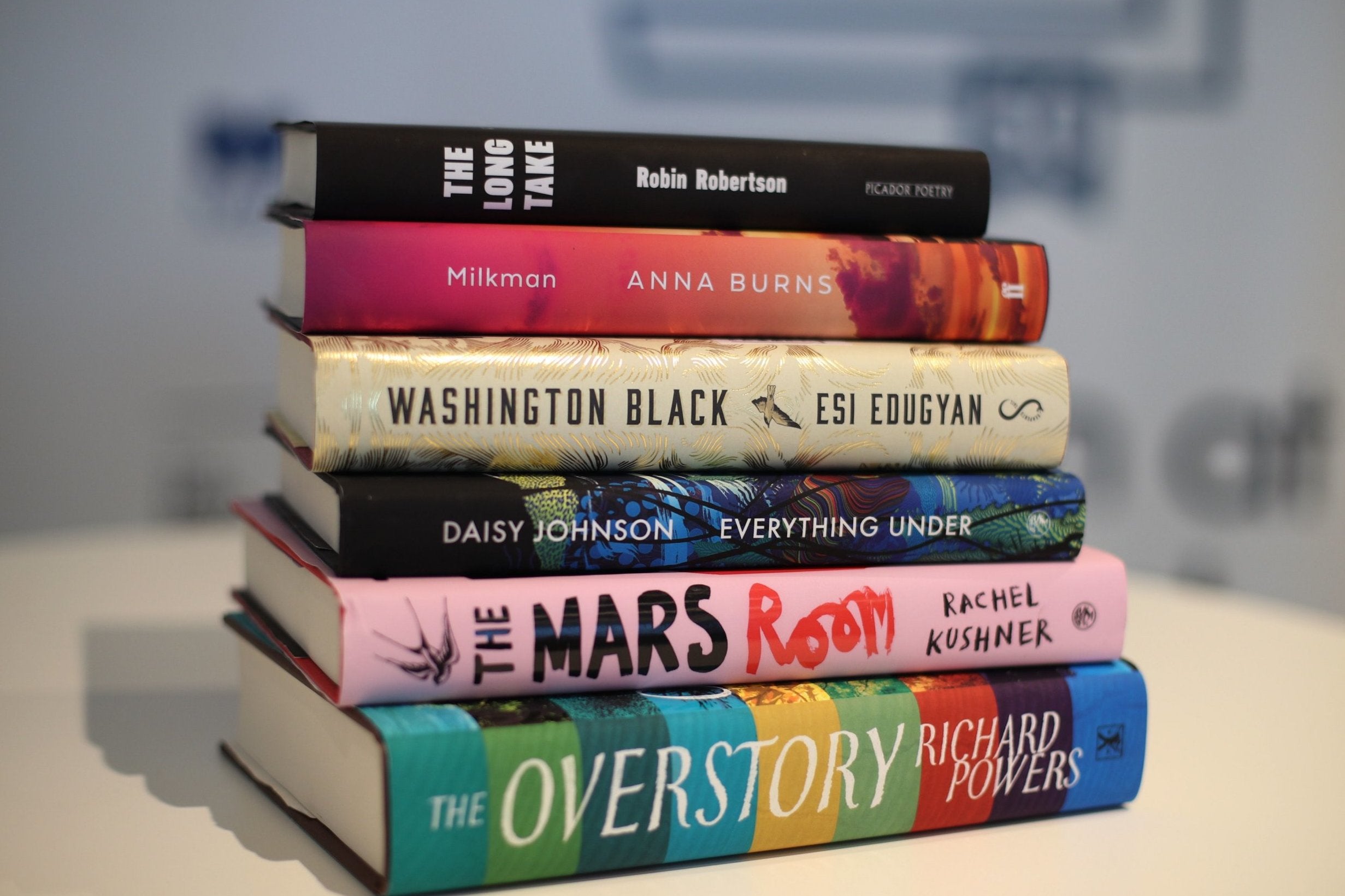

Man Booker Prize shortlist feels so underwhelming because its longlist was so daring

There are some brilliant books here and, more importantly, some fantastic authors with a lot more to give the literary world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One of the biggest causes of outrage when the Man Booker Prize shortlist was announced this morning was the omission of Sally Rooney’s Normal People. Previously touted by many as a favourite to win, the novel is undoubtedly gripping: I read it within a few hours, turning the pages compulsively through the night.

Its pared down, staccato style is very in vogue among publishers and publications right now; the way in which Rooney focused her narrative on the importance of the unsaid in relationships reminded me of Kristen Roupenian’s "Cat Person", the New Yorker short story that went viral a few months ago.

The same tweeters and Facebookers and Redditors who shared "Cat Person" with fervour (guilty as charged) professed their astonishment that Normal People hadn’t impressed the Booker panel enough to make it onto the shortlist today.

Normal People undoubtedly had soul, and often devastated with tiny, razor-like sentences; however, at times, it felt like the (500) Days of Summer of the literary world (albeit with a darker undercurrent very similar to that in Rooney’s first novel, Conversations with Friends, which to my mind is superior).

Unlike some readers, I wasn’t shocked that it was overlooked, though 27-year-old Rooney is a clear contender for a Booker in the future.

Anna Burns’s Milkman, which did make the shortlist, gives the impression of how Rooney might write a dystopia, but its style is more knowing. At one point, the characters debate whether rhetorical flourishes in a passage of text are necessary, and most opt for always being straightforward rather than indulgently overwriting.

It is a book that toys with the idea of feminism, of modernity, of terrorism and its consequences (divisiveness, prejudice, surveillance most of all) while never coming down on one side.

Personally, I preferred the treatment of these themes in Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina, the longlist’s first ever graphic novel, which I thought might have taken too unconventional a form to go further (though ever since Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize for Literature, I’d make no bets on anything). Alas, Sabrina was – criminally – passed over.

Another unconventional addition to the longlist I felt thankful not to see shortlisted was Belinda Bauer’s Snap. Literary judges (and critics) are often accused of turning away from genre fiction because of groundless snobbery, and no doubt that has some truth to it, but this crime novel had a few too many instances of clumsy dialogue and overdone cliches to sit in Booker company.

It’s high time that truly excellent genre fiction did get taken more seriously – Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl would have been a brilliant inclusion a few years ago – but sticking Snap on the longlist wasn’t the best example of how that should be done.

I had already guessed that only one of Snap, Sabrina or epic-poem-slash-unconventional-novel-slash-film-noir-on-paper The Long Take by Robin Robertson would go through, and the latter was the one that made it. The Long Take is a meditative narrative about a veteran wandering across US cities while coping with post-traumatic stress.

The book is about 75 per cent atmosphere-building – though it gains some narrative traction in the middle – and feels like it might not be substantial enough for a win against contenders like Richard Powers’s huge, ambitious tome The Overstory. Still, now I’ve said that, it’ll probably storm to victory.

The Overstory was probably the most traditionally “Booker” of the entire Booker longlist, and for that reason I wouldn’t be surprised to see it win. It’s got a writer referred to in the New York Times Book Review as “one of America’s most prodigiously talented novelists”, a dedication, three long opening quotations (one by Ralph Waldo Emerson), and a narrative that revolves around trees divided into sections titled “Roots”, “Trunk”, “Crown” and “Seeds”.

None of this is to say that it wouldn’t deserve to win. It is a wholesome, ambitious book filled with beautiful turns of phrase – and it feels like a “writer’s book”, but it also feels emotionally honest rather than self-consciously literary.

However, if I’m voting with my heart rather than my head, I would like to see either Rachel Kushner’s The Mars Room or Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black walk away with the prize.

Both are compelling from the opening chapter, with The Mars Room – a tale of life behind bars at a women’s prison, from the perspective of an inmate incarcerated for killing her stalker – unflinching in its portrayal of unsympathetic characters and lives gone irredeemably wrong.

It feels like a bigger, braver, newer look at women’s treatment in modern society than Sophie Mackintosh’s The Water Cure, though the ethereal violence of Mackintosh’s book disarmed me a number of times as well. Kushner’s dialogue, in particular, is excellent, and never feels clunky or artificial even as it gives a diverse cast of characters a voice.

Washington Black is another one that feels very “Booker”, with many of the same themes as The Overstory and The Long Take. Edugyan has a way of concocting astonishingly unusual descriptions which at the same time feel immediately true, with a character “like a blunt axe, wrecking as much as she reaped” and the sound of voices behind a door presenting itself as “a hissing thread”. Like The Overstory, Washington Black feels like it was written with a huge amount of ambition.

Finally, there is Daisy Johnson’s Everything Under. It has had some glowing reviews, but I couldn’t connect with it as readily as the others on the list. It is in some ways a retelling of Oedipus Rex or an epic Homerian journey, in others a comment on gender, in others a contemplative look at fractious family relationships.

Johnson, the youngest shortlisted author (at 27, the same age as Sally Rooney) clearly impressed the judges with the scope of her intentions. However, at times you can feel how much the book wants to be a “sit down and concentrate” experience (which it very much is) and that comes at the expense of clarity in the narrative.

Was this a surprising or groundbreaking shortlist? Not exactly. But there are some brilliant books here and, more importantly, some fantastic authors with a lot more to give the literary world. I think we can count on seeing more than a few of these names on Booker longlists to come.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments