She had a ‘cool’ childhood babysitter. Four decades later, she learnt he was a serial killer

For years, Liza Rodman remembered Tony Costa as the fun, trustworthy man who looked after her in the Sixties. She and co-author Jennifer Jordan tell Clémence Michallon how the truth came to light, and how the two friends wound up investigating his crimes together

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The first time Liza Rodman’s babysitter, Tony Costa, took her to his “secret garden”, she was puzzled. At the age of nine, she considered herself a garden connoisseur. Her farmer grandfather had taught her how to grow tomatoes and lettuce, among other “really cool things”. So when Costa told her about his garden in the woods of Truro, Massachusetts, Rodman thought her expertise would be of use. But upon arriving, she felt confused and underwhelmed.

“The first thing that really came back to me was, ‘What kind of a garden is this? What are we looking at?’” Rodman recounts on the phone decades later.

That question – what are we looking at? – wouldn’t get a proper answer until 2005, when Rodman found out that her beloved childhood babysitter, the “cool”, “unguarded” young man who gained her trust and admiration as a child, was a serial killer. And that “secret garden” of his? It served as a burial ground for four of his victims.

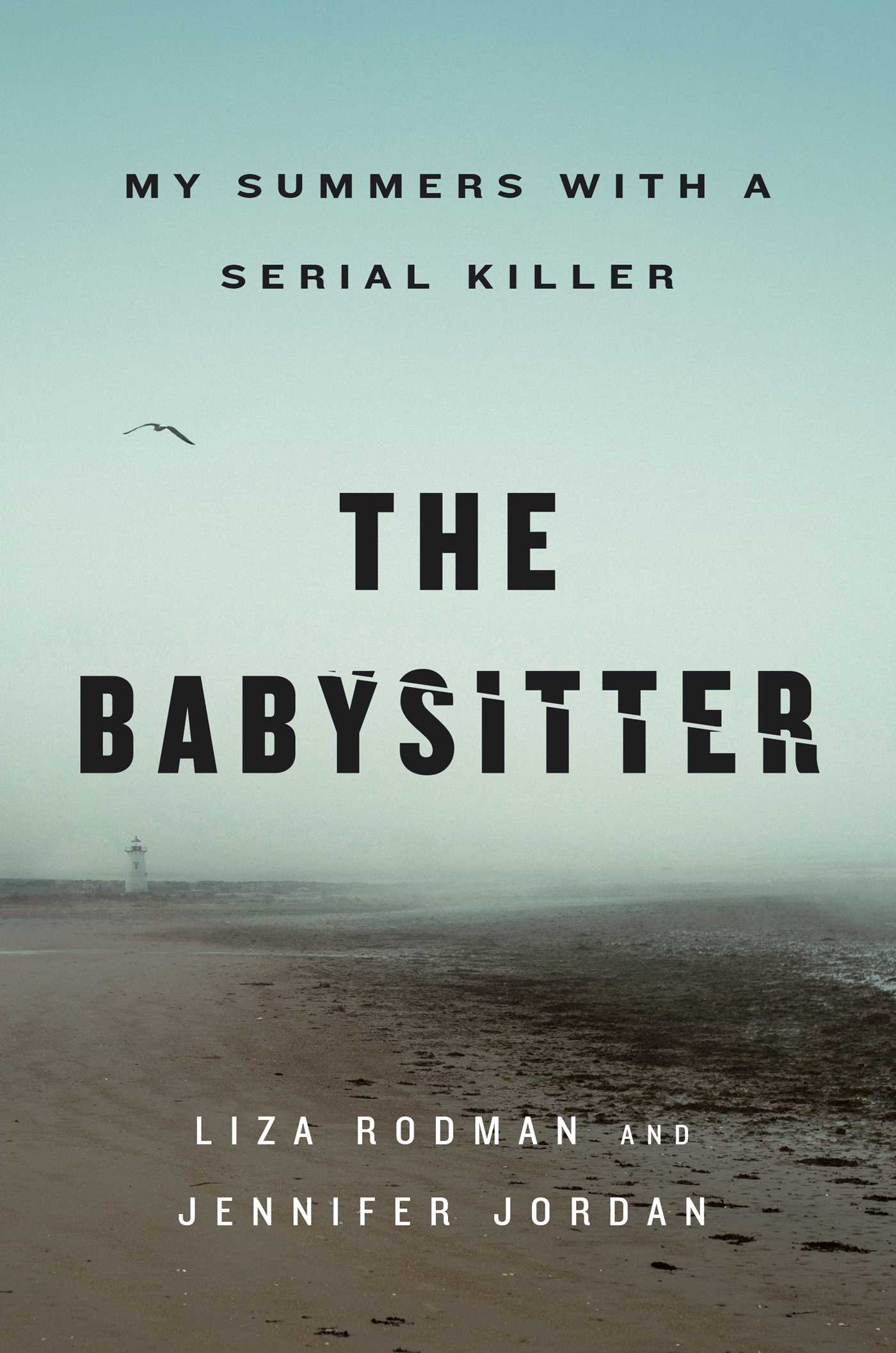

That realisation is the subject of The Babysitter: My Summers With a Serial Killer, a new book co-written by Rodman and her longtime friend Jennifer Jordan. The book continues a tradition started by Ann Rule’s The Stranger Beside Me, her account of working with serial killer Ted Bundy before the world, including Rule, became aware of his crimes. The Babysitter innovates by telling Rodman’s and Costa’s stories in alternating chapters, and is a compelling, sensitive hybrid of memoir and true crime.

Antone “Tony” Costa was born on 2 August 1944 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was 18 when he married his 14-year-old bride, Avis, at a Catholic church in Provincetown. Costa fathered three children, got divorced, worked construction jobs, established himself as the leading drug dealer in the freewheeling community of Provincetown (a seaside town at the northern tip of Cape Cod), and assembled a posse of teenage boys (whom he referred to as his disciples) and girls (his “kid chicks”) who followed him around “like a guru”. He was also, as Rodman and Jordan recount, responsible for the deaths of five women, four of whom were found buried in the Truro woods.

For most of her adult life, Rodman did not know any of this. After Costa’s murder trial, she “never learnt” what happened to him – and, she writes in The Babysitter, “by the time the summer of 1970 rolled around, I stopped asking”. Then, in the 2000s, she started having violent nightmares. For two years, they involved “an anonymous man with a knife or gun”. In 2005 came the nightmare that changed everything: the man was no longer anonymous. It was Tony Costa, and Rodman couldn’t figure out what he was doing in her dreams.

She asked her mother. “I don’t get it,” Rodman said. “He was always so nice to me. What do you remember about him?”

“Well,” Rodman’s mother answered. “I remember he turned out to be a serial killer.”

When Rodman expressed her dismay – “Our Tony? A serial killer?” – her mother dismissed her concerns. “Yeah, so what?” she said, according to Rodman’s own recollection. “He didn’t kill you, did he?”

As Rodman tells it, the most startling element was that not only had she never been afraid of Tony, but that he was a rare trustworthy adult figure in her life. In The Babysitter, she recounts a difficult childhood. Costa, meanwhile, was like that older cousin who “knew all the cool music and had the right bell-bottom jeans and the really cool shoes”.

“He was a little bit older and he had kids and a wife and he wasn’t as accessible as a cousin is, but he was cool,” Rodman says. “Sometimes you meet people who are guarded, and I just didn’t feel that way about Tony. He was not a guarded person. I just remember him always darting around, always doing. He was a doer.”

Throughout The Babysitter, Costa ferries Rodman and her younger sister around in his car – each trip the beginning of a fun adventure for the young Liza. He reaches into his pockets and pulls out change for the girls to purchase ice lollies. He sings along to the radio in the car. He looks “like Elvis Presley”, with his “hair slicked back with Vaseline and a sly smile on his face”. His presence comes in sharp contrast with her unhappy home life.

After learning the truth about Costa in 2005, Rodman shared the story with Jordan. The two, now 62, met four decades ago, when they were both students at the University of Massachusetts. (Jordan was brewing coffee with her own percolator; Rodman, tired of drinking poor-quality joe, was attracted by the smell and knocked on the door of Jordan’s dorm, coffee mug in hand.) For years, Jordan, an author, film-maker, and screenwriter, urged Rodman to turn her experiences with Costa into a book. Rodman kept circling around the issue, until finally, Jordan’s professional schedule cleared and she offered herself up as a co-author.

There is an evident vulnerability to Rodman’s account. But the narrative she paints is straightforward, unwavering in its clarity: she trusted and liked Costa as a child because she had no reason not to. She trusted and liked him because she didn’t really know him.

Both women apply the same intellectual rigour to their present-day examination of Costa’s crimes. They take pains to portray his victims as fully fledged human beings, with respect and humanity. The two women Costa was convicted of murdering were Mary Anne Wysocki and Patricia Walsh, two friends who had attended high school and university together. (Walsh was a teacher; Wysocki was hoping to become one.) The remains of two others, Sydney Monzon and Susan Perry, were also found in the woods in Truro. Prosecutors didn’t try him for their murders, opting instead to focus on the cases of Wysocki and Walsh, for which they had more evidence, according to Rodman. A few days after our initial conversation, she notes in an email about Monzon and Perry: “They never received justice.”

The fifth woman, Christine Gallant, was found kneeling face down in a bathtub, having died of what Rodman and Jordan describe as a “monstrous dose” of a barbiturate. She had three cigarette burns on her chest and a bruise on her shoulder. While Gallant’s death was ruled a “possible suicide” due to the presence of barbiturates in her system, the authors make a compelling case against this theory, based on the position of Gallant’s body when it was found, the burns on her chest, her concerning relationship with a divorced Costa, and the fact that she intended to marry another man. In the book, Rodman and Jordan write that Costa “accidentally or intentionally” administered the overdose, concluding: “Once again, Tony Costa was the last known person to see a young woman alive.”

In their examination of Costa’s crimes, Jordan and Rodman researched the lives of three more women whose names came up in discussions of the serial killer’s potential victims. All three did die, but it turned out their deaths had nothing to do with Costa. Those revelations give heft to the book and the investigative work that bolsters it. True crime can be a messy genre, prone to speculation and approximation; Jordan and Rodman’s thoroughness is a reminder that truth matters. “The families of those three women had no idea that their mothers and sisters had been [falsely] attached to a serial killer,” Jordan says. “They had no idea that this Tony Costa person was living and killing on the east coast and that their three family members were somehow linked in this dark way.”

Realising as an adult that your cherished childhood babysitter was a serial killer sounds like it would shake one’s faith in people, both strangers and loved ones. When I bring up the topic with Rodman, she says she has “no real ability” to trust: “I wouldn’t know trust if it were sitting next to me, patting my thigh and saying, ‘This is what it is; this is what trust is.’ I don’t know what it is and I don’t know what it feels like.”

Her experiences with Costa probably played a part, she says, among other personal experiences. “I was sort of used to people disappearing. It wasn’t a very trusting environment ... I’m amazed at people who had warm, nurturing parents, because that just wasn’t our experience. Trust is an issue.”

The Babysitter: My Summers With a Serial Killer is published by Atria Books (Simon & Schuster)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments