Liv Little: ‘I need to deal with gal-dem’s closure from a place of gratitude’

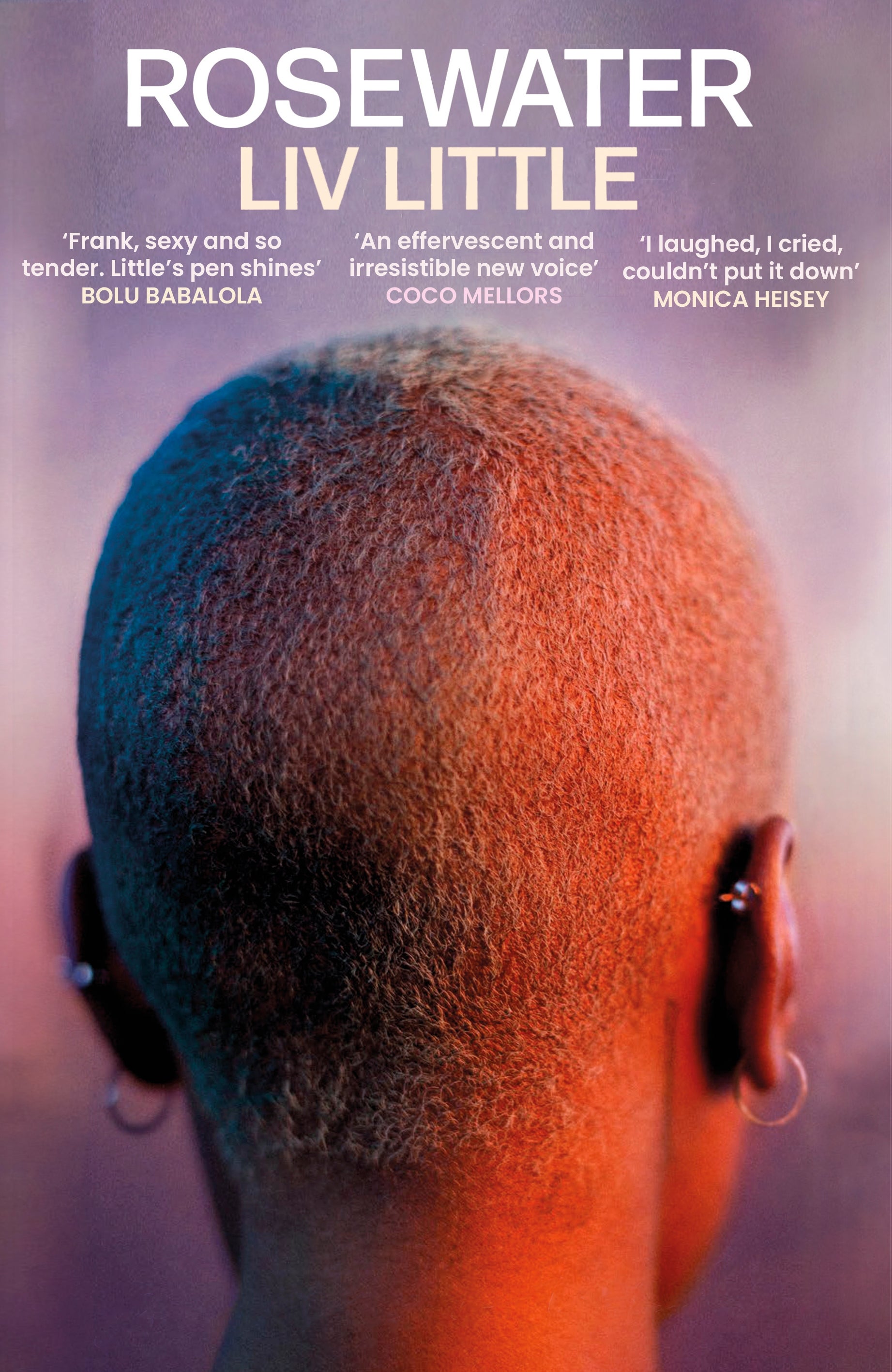

After becoming a CEO at 21, gal-dem founder Liv Little had to walk away for the sake of her health. As she publishes her debut novel, ‘Rosewater’, she talks to Nicole Vassell about her creative career, love and loss, and gal-dem’s recent closure

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Liv Little cannot get sick. Not this week. A pot of raw ginger and hot water boils on the hob, while echinacea drops and herbal tea sachets decorate her dining table. “Don’t come too close!” the writer warns me as a greeting. “I think I’m getting ill and I just can’t let that happen right now.” We’re talking in the last few days before her tender debut novel, Rosewater, hits the shelves. Her calendar is chock-full of promotional commitments; every five minutes, her iPhone pings with new messages. And, yet, while we’re together, Little ignores each notification and gamely focuses on the conversation at hand. The former gal-dem CEO has, she tells me, waited her whole career for this moment. A common cold won’t be the thing to stop her now.

We’re in her home for the week: a stylish studio suite in a central London hotel. Little, 29, moved to the Kent coast during the pandemic, but is enjoying the brief return to her home city. Hot on the heels of shooting her first short film, the details of which she’s sworn not to share, Little is now fully and blissfully divorced from her past career path as a media mogul. In 2015, she founded gal-dem, an online magazine that put the perspectives of women (and people of marginalised genders) of colour at the forefront.

Launched as a student project, borne out of Little’s frustration with the lack of diversity at the University of Bristol, the publication grew to be a nationally recognised outlet and launched the careers of countless journalists. Little eventually stepped down from the company in 2020, and ever since she’s turned her creativity more towards fiction than reportage. As she hands me a mug of ginger tea, she admits the switch has been “really fulfilling”. Dressed in a matching grey sweatshirt and tracksuit bottoms, with gold rings stacked on most of her fingers, Little crosses her legs on the sofa. Right now, she’s the picture of cool relaxation, with a calm, steady voice to match. But the last two years, which have included the recent closure of gal-dem, have been “a mixed bag”.

You could say that she’s spent the last few years figuring out where in the world she fits best. That question is also the main preoccupation of the vibrant and lyrical Rosewater. Our protagonist is Elsie, a talented poet in her late 20s whose already fragile sense of stability is destroyed when she’s suddenly and callously evicted from her flat. Combine that with her being estranged from her best friend Juliet and her immediate family, her meagre pay cheque bartending at a local gay bar and the overwhelming sense of feeling that she’ll never “make it” as a poet, and it’s easy to see why Elsie is riddled with anxiety. Though she’s never unconfident about her Blackness, her queerness, or her way with words, Elsie is unsure whether there’s a place where she can truly stand tall.

“She’s unwavering in who she is,” Little notes, “it’s how the rest of the world receives her.” Throughout the book, Elsie must pick herself back up again and allow the people who care about her to help. And, along the way, she falls in love with someone unexpected, which leads to some of the best romantic writing I’ve read in years.

“I’ve had a whole lot of love in my life,” she says of her own affairs of the heart. “I love my friends hard and deep – I tell them, and I squeeze them, and I make them know I appreciate them. I want people to feel the love. And the same with my partner – I want the best for her, and she does for me; we want to see each other shine.” A brief pause. “I’ve seen the impact of feeling like you don’t have that. I saw the challenges that my dad experienced, with him not feeling like he had the love and foundation that he wanted.”

Little’s father, Harry Little, comes up in conversation often. During the writing and editing process of Rosewater, he was diagnosed with motor neurone disease and, a year ago, succumbed to the brain and nerve condition. Understandably, Little looks back at the time she was writing her novel as the “most challenging” period of her life. That she managed to create such an exquisite story, despite what was going on in reality, is remarkable. For her, creating Rosewater was something of a life raft in the middle of a turbulent sea storm.

“I definitely am not glad that I lost my dad – it’s horrific, and I wish he was here. But I also know that the depth of the feeling that I experienced, through caring for him, through losing him, has made me an infinitely better writer and maker of things. You don’t even know how deep you can feel until you go through something like that,” Little says. Despite the excitement of her book launch, she admits that this week stands as a big reminder of his absence. “My dad didn’t read books; he wasn’t going to ever read mine, but he was so proud of the fact that I had written it. Just knowing that he’s not going to be here for key milestones is really s**t,” she says, with an emotional croak. “It hits you again.”

Perhaps there’s some consolation in the fact that Little hit plenty of milestones while her dad was still alive. By the time she’d graduated from Bristol in 2016, a first-class politics and sociology degree in tow, gal-dem was well on the way towards becoming an esteemed brand with a staff of 70. With live events at venues such as the V&A Museum and a takeover of Guardian Weekend magazine in 2018, the site was leading the way for inclusive, forward-thinking British journalism. Before Little knew it, she was a public figure at the head of a major company.

“I wouldn’t say I’m an accidental CEO, but I was 21 when I started gal-dem, and a lot happened really quickly,” Little says, slightly more hesitant than before. “The reality is, it’s very hard to be a Black woman in that leadership role, and people don’t know it. It’s very hard to raise money for mission-driven stuff. When you’re 21, it’s great; you go in with this youthful naivete – and then you start to realise that things are actually, really complicated.”

In time, not only did she crave the freedom to tell her own stories, but the grind of moving through an industry with ever-reducing resources and constant signs of bias towards white, upper-class men was mentally crushing. She eventually stepped away from the brand in 2020. “It was a beautiful thing, and I learnt so much,” Little explains. “I worked with amazing people who’ve become incredibly important in media. But by the time I left, I was really unwell. I was so overwhelmed and overworked. For a long time, I didn’t feel as if I was able to breathe.” Like Elsie, Little was having regular panic attacks from the stress of long days and ever-increasing directorial responsibilities. Her partner and family feared for her health.

We’re talking less than three weeks since the announcement that gal-dem would cease publication after eight years, due to financial hardship. When I ask how she’s feeling about it all, Little sighs heavily. “It’s sad, of course,” she begins. “But I feel like in these moments, it provides space for new things to be born in its place. Endings are hard, but I just want to exist in a space where I’m really proud of the work we did. Gratitude needs to be the space I deal with it from.”

Journalism and publishing are both industries that have come under fire for continuously falling short of representing a wide range of perspectives. With the decennial Granta list causing online debate by naming only two Black authors in a list of 20 young British novelists to watch, how does it feel now being in another industry where there are still significant strides to be made on matters of inclusion?

“I feel like I’ve spent so much time talking about all the ways in which people can and should do better,” Little replies matter-of-factly. “Also, I feel the onus is on the people in positions of power to change things. We know what they need to do, it’s quite straightforward, but they’re not doing it. All I can focus on is trying to contribute to the kind of stories that I want to see and that I think should be told.”

When it comes to her future, though, Little has no desire to return to media any time soon. In an ideal world, she’d finish up her Masters in Black British literature, alongside working on her next book and some TV and film projects she can’t yet discuss. As we finish up our cold-busting teas, Little’s thrill at her burgeoning creative career brims over. “Sometimes, I’m like: is this real?” she asks. Indeed, it is – and with her talents, discipline and contagiously optimistic outlook, there’s no doubt that this is merely chapter one of her next success story.

‘Rosewater’ is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments