Laurie Lee: As I walked out one Midsummer morning

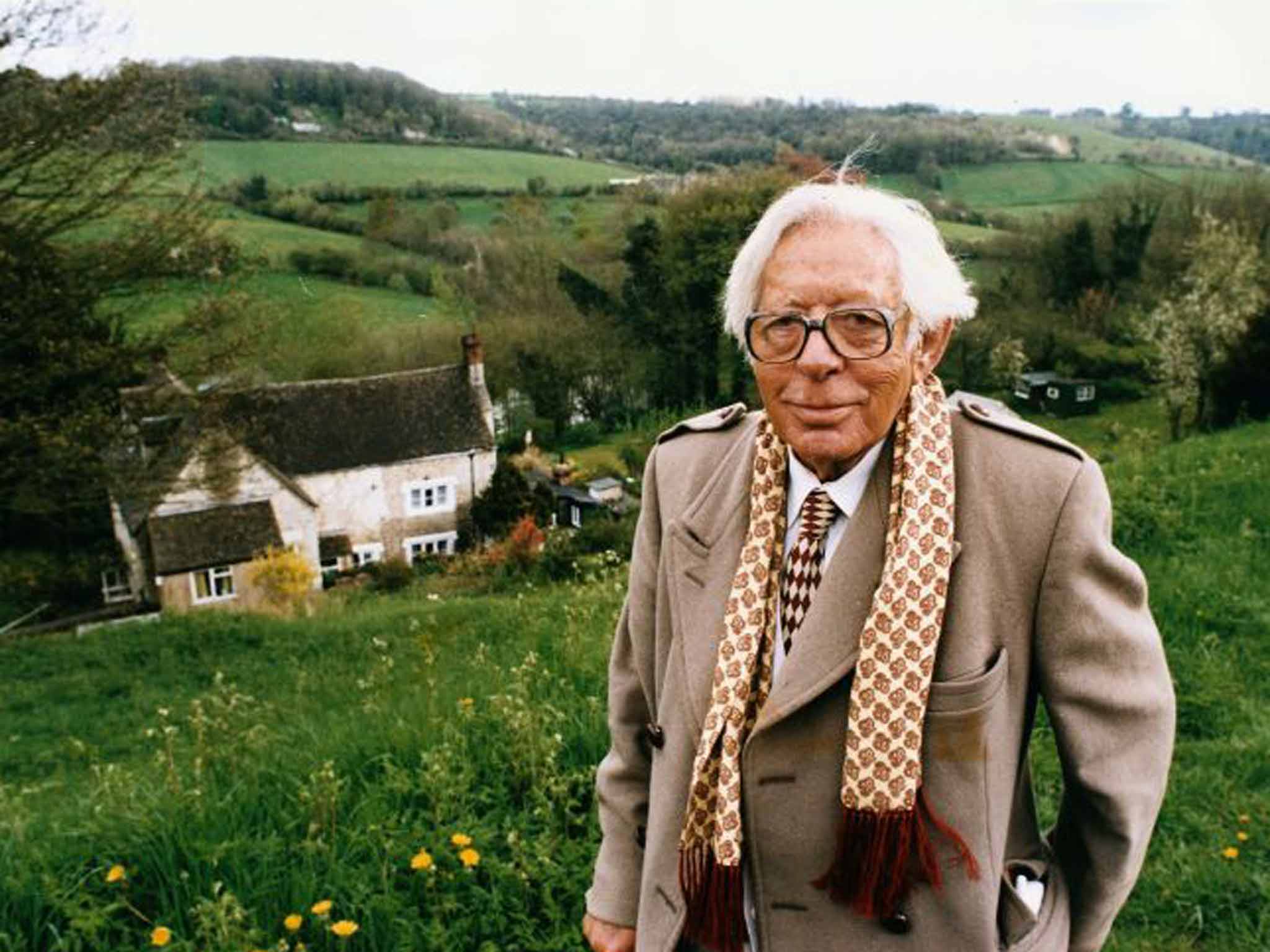

A century ago tomorrow saw the birth of Laurie Lee, whose most famous work, Cider with Rosie, immortalised the countryside of his youth. Boyd Tonkin strolls through the Slad Valley to see what remains of its celebrated past

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Somebody at the Gloucestershire Wildlife Trust must have a keen sense of humour – or, perhaps, a feverish erotic imagination. Tomorrow, on the centenary of Laurie Lee's birth, the singer and writer Cerys Matthews will open a waymarked trail around his beloved Slad Valley. Already a wildlife walk, the route now sports 10 larch posts with Lee's poems inscribed on glass panels. So, through the woods that still, as in Cider with Rosie, ooze "over the lips of the hills like layers of thick green lava" and across limestone grasslands frothing with wildflowers in "a massed entanglement of species", the walker will see the writer's world – literally – through his words.

I tramped this landscape of the heart on a perfect day of Lee's "June summer, with the green back on earth and the whole world unlocked and seething". At one point, a punishingly steep path rises sheer through the ancient beeches of Longridge Wood. Breathless at the crest, you suddenly see the open meadowlands of Slad Slope swoon away before you, bright with butterflies and carpeted in flowers. At this spot, the poetry-post gives you Lee's frankly post-coital Landscape, with its sated female body adrift in an orgasmic haze "like a covered field". Mounds, curves, thickets, hollows and declivities sprawl in the sun. To his followers, Laurie ("Lee" always sounds absurdly, officiously wrong) has always meant not just pretty Cotswold countryside but the pagan sensuality that animates the land in all his work.

In his memoir, he recalls the Slad of his 1920s childhood as "a deep-running cave still linked to its antic past", its shadows "cluttered by sprits and by laws still vaguely ancestral". Above all, as every reader if not every planning inspector knows, Laurie enchanted Slad and its valley into an intensely and archetypally female place. A textbook mother's boy, estranged from his absent father, he was first cossetted by the maternal heroism of Annie Light and his sisters in Slad, then lapped in love by one devoted, exasperated woman after another (his two daughters, Yasmin and Jessy, among them).

"I was perfectly content in this world of women", Cider tells us, in a single line that sums up a lifetime. A later friend and landlady, Virginia Cunard, told Valerie Grove for her exemplary biography (now reissued as The Life and Loves of Laurie Lee) that "the telephone never stopped ringing for Laurie. He had more people in love with him than anyone I've ever met". Novelist Rosamond Lehmann, also a friend, thought him "a dangerous person for women" precisely because he mixed seductive charm with a vagabond spirit.

In this centenary year, that lazy charisma persists. His charm in print and person has helped to safeguard a landscape "farmed and fenced by literature" – the words of poet Adam Horovitz, who grew up in Slad and evokes his own childhood, 60 years post-Rosie, in his memoir A Thousand Laurie Lees. The old mill town of Stroud does fling the odd urban ribbon up into the sacred valley – a touchy topic, as we will see. However, as you leave the last houses behind, it still feels as if someone has thrown a scenic time switch. The settings of Cider with Rosie lie plump and juicy up ahead, astonishingly intact. Its author's grave stands outside the simple late-Georgian church. It commands a ravishing view over what the inscription calls "the valley he loved". On the reverse side, his poem April Rise affirms that "If ever I saw a blessing in the air, I see it now in this still early day". Yet he never sought to romanticise a rural working-class life that carried more burdens than blessings. The adjacent headstone tells you why.

It records not only Robert Ryman but his and wife Rebecca's daughter, Emily Ann. Her dates? 2 June 1866 to 9 March 1867. Her first Slad winter killed Emily Ann. Even in the 1910s, the frail, bronchitic Laurence might well have ended his brief span as another infant statistic. When I visit, the valley does feel like "a jungly, bird-crammed, insect-hopping suntrap". He always made clear that it could also be not a pastoral paradise but a purgatory of "lashing rain", and "children dying of quite ordinary diseases like whooping cough". In one of the memoir's darkest episodes, local people conceal the identity of murderers, who had brained a braggart returnee for his pocketful of money, solely because "they belonged to the village and the village looked after them".

Once a small manor, then an alehouse, the T-shaped 17th-century cottage where the Lees lived from 1918 still nestles in its hidden dell below the road, with "its walls so thick that they kept a damp chill inside them whatever the weather". Mid-June, and a wall of roadside flowers almost conceals it from view. Here, scatty, anarchic, affectionate Annie and her brood of seven from two marriages (Laurie belonged to the second) lived "in the downstroke" of the T.

At The Woolpack, where the local boy-made-good would hold court from the early Sixties up to his death in 1997, a lunchtime customer from Sydney bears witness to the Slad lad's global cult. This Saturday, the pub will stage a cider and flamenco festival, the latter in honour of Laurie's Spanish journeys recorded in his second and third volumes of autobiography: As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, and A Moment of War. The Woolpack is now owned not by some grizzled Cotswold innkeeper but by artist Dan Chadwick: the son of sculptor Lynn Chadwick, and once a member of avant-garde starchitect Zaha Hadid's design team. Keith Allen, father of Lily, has been known to pull pints behind the bar. Adam Horovitz remembers Damien Hirst, in his pre-sobriety days, presiding over "nights of anarchy" there. With Uley Brewery real ale, you may now dine on hake, clams, samphire and salsify. Thanks to Laurie, Slad can never be a wholly ordinary village again.

In 1959, Cider with Rosie brought overwhelming mid-life acclaim to a gifted but feckless poet and screenwriter whose most conspicuous role thus far had been to compose the texts for the Festival of Britain. His offbeat humour and taste for eccentricity had made him, in effect, the Danny Boyle of 1951. Then, after years of procrastination ended by a fertile summer not in the Cotswolds but on Ibiza, Cider matured at last. A flash flood of fame made it possible to save as well as celebrate the childhood scenery that Laurie adored. In the Sixties, reinstalled in a cottage near the pub, he had bought a stretch of woodland above Slad that now bears his name to preserve it from piecemeal destruction. In 1995, his voice raised in protest helped to head off a housing development and so forestall (his words) "a self-inflicted wound that not even time will heal".

Now the wound may open again. By a curious accident of fate, the centenary month has coincided with a planning inquiry into the proposed construction of 112 new homes on Baxter's Fields, a "green wedge" of land on the fringe of Stroud that serves as a kind of curtain-raiser to the valley. The steep site is not huge, already has some fairly nondescript housing overlooking it, and stands far from Laurie's iconic village. But I can confirm the Slad Valley Action Group's argument that "the green wedge is what catches the eye", a taste or tease of lush, unspoiled terrain that the valley as a whole then amply fulfils. The campaign's closely argued challenge to the scheme maintains that, thanks to this natural finger, "green landscape appears to stretch right into the heart of Stroud".

Stroud District Council unanimously refused the housing application from the Cheshire-based greenfield specialists Gladman: a land developer "obsessed with winning consents", according to its website. "Think 14 months not 10 years", Gladman exhorts prospective clients as part of a gung-ho pitch that promises consent for developments at "minimal risk" and in "a short timescale". Gladman appealed against the initial refusal, and a public inquiry ended earlier this month. Both sides now await the inspector's verdict. During the hearings, English literature bizarrely collided with planning legislation. Gladman's lawyers argued that the exact locations in Cider with Rosie remain elusive. True, but Gladman's dismissive references to "landscapes of the mind" only show how pervasive the link between work and place can be. The best-beloved corner may not be locatable via satnav, but any nook within the desired body of this land. And few local planning disputes can have elicited – as this one has – letters of objection from Nepal, Japan, the Philippines, Australia and Mexico.

When the campaigners talk of the area being "immortalised by Laurie Lee", the stock phrase for once escapes cliché. Laurie has given this landscape a chance of survival. However lovely, some neighbouring districts in Stroud's necklace of five valleys will not enjoy that. John Marjoram – deputy mayor on Stroud town council, and one of its Green Party majority – alerts me to other housing proposals for nearby Rodborough Common and The Stanleys. "We're being bombarded by the day," he says. "We've got a massive application in Stonehouse for 1,500 homes. I've been on the planning committee for 28 years and I've never seen it so bad."

However, even David Cameron – a Cotswold MP, after all – has hinted that he would disapprove of a new estate in the valley. "I think that would give a clear indication to an inspector," says Mr Marjoram. "It's very clear that there would be absolute uproar about this if it did go ahead. Absolute uproar." In Stroud and Slad at least, the much-loved pen may still prove mightier than the developer's sword of cash. "I think that the connection with Laurie Lee will probably save this case," he concludes.

As they say in Connemara, you can't eat a landscape. All the same, you can plan to eat from controlled measures of the tourism that a fabled scene can bring. "Lose that sense of uniqueness, the beautiful views," warn the Slad Valley preservationists, "and slowly but surely we will lose the tourists – and certainly we will never see the growth in tourism that local businesses want."

In that classic motto for the conservationist, Prince Tancredi in Lampedusa's novel The Leopard says that "if we want everything to remain the same, everything must change". Smart and vigilant activism has protected and even recreated the settings of Cider with Rosie, a book that purports to record "the end of a thousand years' life" even though it portrays a globetrotting family who worked in the farthest reaches of the British Empire. They belonged to modern history, not to bucolic legend. So did the author, who kept up his flat in Elm Park Gardens, Chelsea, even as he joked and yarned in The Woolpack.

Laurie Lee was always something of a Bollinger Bumpkin. (Aptly enough, the courtyard of the pub now has a table canopy that advertises not some tea-brown local ale but Pol Roger champagne.) But Adam Horovitz applauds Dan Chadwick for his "velvet revolution" at the inn, now "the sort of pub one might imagine walking into if one were thirsty after a backward jaunt in a time machine". After all, pristine peasant life, and pristine peasant landscape, has hardly existed in England for 300 years. The Slad Valley campaigners put it neatly when they note that this rustic idyll is "characterised by land management with a generally light hand. It is by no means natural but it is certainly not regimented."

Via tweaks, nudges and discreet improvements, its qualities remain. Much as I enjoyed the freshly installed poetry-posts, once or twice I felt that they stood a bit clumsily in the sightlines of a glorious view. Can I be the first to complain about this act of desecration? Not really – and certainly not about the poem engraved on its sculpted trunk in the deep shade of Frith's Wood. This, again, is April Rise, with its infectious joy in a place of renewal and revival: "Now, as my low blood scales its second chance, If ever world were blessed, now it is."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments