Karl Marx at 200: Ten left-wing writers who followed in the footsteps of a giant

As the revered political thinker marks his bicentenary, we look back at a selection of authors who addressed socialist causes and ideas in their fiction

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Today is the bicentenary of Karl Marx (1818-83), an anniversary being observed around the world.

So what better time to dig out that battered teenage copy of The Communist Manifesto (1848) and all three groaning volumes of Das Kapital (1867-83)?

If the scale of that undertaking sounds daunting, fear not. Here is a selection of left-leaning writers who followed in the political philosopher’s wake, using fiction as a more readily digestible means of bringing socialist ideas to the reading public.

Emile Zola (1840-1902)

The great French novelist’s 20-volume series Les Rougon-Macquart sought to encompass all aspects of contemporary society in the manner of Honore de Balzac’s mammoth La Comedie Humaine (1829-47).

Zola’s panoramic novel sequence comprised thrilling but naturalistic tales of the working lives of everyone from prostitutes to train drivers and crooked financiers in works like Nana (1880), La Bete Humaine (1890) and L’Argent (1891).

Few books could be more prescient than Germinal (1885), his account of coal miners toiling by lamplight in the fictional northern town of Montsou who are driven to strike by the conditions they suffer – with disastrous consequences.

The novel captures the same spirit of compassion the young Vincent van Gogh felt when he witnessed the brutal lives of those swinging picks in Borinage, Belgium, presenting the dank horrors of the tunnels in unflinching, journalistic detail.

Charles Dickens had carried out a similar act of reportage when he visited Preston by rail in 1854 and reported back on the industrial action he had observed in his Household Words essay “On Strike”, the inspiration for that same year’s Hard Times, in turn capitalising on a contemporary interest in workers’ rights also addressed in fiction by the likes of Elizabeth Gaskell in Mary Barton (1848).

The recognition of Germinal and the public service it provided was such that its title was chanted by mourners at Emile Zola’s funeral in 1902.

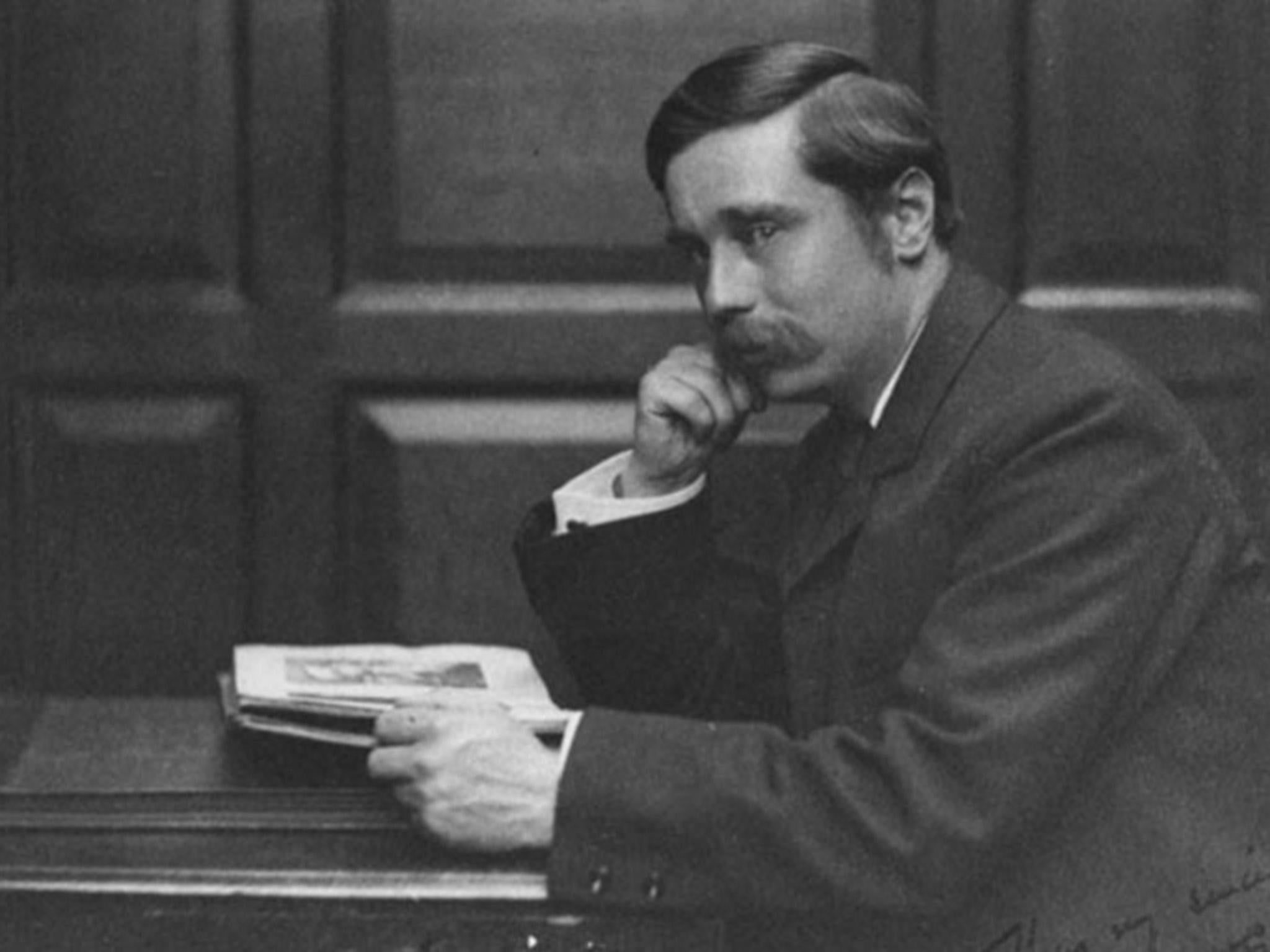

HG Wells (1866-1946)

Born in Bromley, Kent, the son of a shopkeeping cricketer and a lady’s maid, Herbert George Wells abandoned an early career as a draper’s apprentice to serve as a pupil-teacher in Wookey, Somerset, and then at Midhurst, West Sussex.

Winning a scholarship to study biology at South Kensington’s Normal School of Science under TH Huxley, a friend and champion of Charles Darwin, Wells committed himself to a path of scholarship and debate, fascinated by the potential of science to create a fairer world – and wary of its capacity for misuse, describing human history as “a race between education and catastrophe”.

He is best remembered today for the purple patch that saw him write the seminal science fiction novels The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Dr Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897) and The War of the Worlds (1898).

Wells addressed his hopes and fears for the future of society either side of the First World War in Anticipations (1902) and The Shape of Things Come (1933) and his support for the New Woman in works like Ann Veronica (1909) and The New Machiavelli (1911). Dr Moreau’s Panther Woman, according to Margaret Atwood, represents the fearsome potential of the modern woman.

An important early advocate for the suffrage movement, Wells was also a believer in “free love” with a reputation for womanising that scandalised his peers in the Fabian Society.

This prophet of the future – who preached socialist principles from a young age, stood as a Labour candidate in 1922 and 1923 and met both Lenin and Stalin at the Kremlin – became increasingly pessimistic about the prospects of utopia following the brutal introduction of mechanised warfare in 1914, calling for Whitehall to introduce a “Department of Foresight” to look ahead to the world of tomorrow.

He came to believe that only a world government could save us from further global conflict and falling victim to the megalomania of men like Griffin in The Invisible Man.

The title of his final work, Mind at the End of its Tether (1945), said it all, but this visionary was nevertheless hailed as “an important liberator of thought and action” by Bertrand Russell.

Robert Tressell (1870-1911)

One of the most beloved of all socialist novels, The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists was published in 1914, three years after its author – real name Robert Noonan, a sign writer – had passed away.

The book boldly confronts the working-classes for resigning themselves to their unjust lot, accepting that wealth and comfort are “not for the likes of them” in order to turn a profit for their corrupt masters.

Set in the fictional town of Mugsborough, the novel attacks the capitalist system for allowing exploitation, embezzlement and hypocrisy to prosper at the expense of a fair deal for labourers.

Noonan died of tuberculosis aged just 41, his ambition to see his 1,600 page manuscript published unanswered and was buried in a pauper’s grave in Liverpool. Only the efforts of his daughter Kathleen saw the dream realised posthumously.

George Orwell reviewed The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists in The Manchester Evening News in 1946, praising it for capturing “the actual detail of manual work and the tiny things almost unimaginable to any comfortably situated person which make life a misery when one’s income drops below a certain level.”

The book underwent a revival of interest when BBC Radio 4 broadcast a new dramatisation at the height of the financial crash in 2009, chiming perfectly with the angry public mood that birthed the Occupy movement.

Liverpool’s Everyman Theatre staged a new theatrical production the following year.

Upton Sinclair (1878-1968)

Baltimore-born Upton Sinclair wrote almost 100 books over the course of a long career and was unafraid of tackling major subjects like exploitative yellow journalism in The Brass Check (1919) and fossil fuel gangsterism in Oil! (1927), the basis for Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (2007).

But it was one of his earliest that would prove his most influential.

The Jungle (1906) tells of Lithuanian immigrant Jurgis Rudkus, who arrives in America and is put to work in the slaughterhouses of Chicago’s stockyards, falling prey to unscrupulous conmen, forced to live in slum housing and amass debt while enduring unsafe and unsanitary working conditions.

Jurgis ultimately finds support in the brotherhood of a trade union, but not before his wife Ona has been raped and driven into prostitution and morphine addiction and his son eaten by rats.

The literary equivalent of George Bellows’ gory painting Carcass of Beef (1925), Jack London called The Jungle “the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of wage slavery”.

Sinclair’s novel caused such outcry upon publication that Congress hurriedly passed both the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act to improve conditions for workers in the American meatpacking industry. It is also a scalding polemic about America’s treatment of immigrants, inferring that new arrivals at Ellis Island are processed, exploited on pittance salaries and disposed of when no longer needed like so much cattle.

John Steinbeck (1902-1968)

The great American writer was a prolific documentarian of his native California, writing about the lives of itinerant working men and Mexican migrants in novels like Tortilla Flat (1935), Of Mice and Men (1937), Cannery Row (1945) and East of Eden (1952), recording their hopes and dreams, the hardships they endured and the legacies they left behind.

Still widely read, Steinbeck’s crowning achievement is undoubtedly The Grapes of Wrath (1939), for which he won the Pulitzer Prize. Its protagonist, Tom Joad, is an Oklahoma farm hand driven out of the Dust Bowl with his family and thousands of others by economic hardship to seek a new life in the Promised Land of the west coast.

The strength of the novel – famously filmed by John Ford in 1940 starring Henry Fonda as Joad – lies in its profound sympathy for its working-class characters and outrage at the indignities inflicted upon them by the “greedy bastards” responsible for bringing America to its knees during the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

Folk troubadour Woody Guthrie, a fellow “Okie” with the proto-punk slogan “This Machine Kills Fascists” emblazoned upon his guitar, closely identified with the book and wrote both a song about Joad and an album called Dust Bowl Ballads in 1940.

Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Billy Bragg and many others have all since followed his example in bringing popular protest against matters of social injustice to the mainstream.

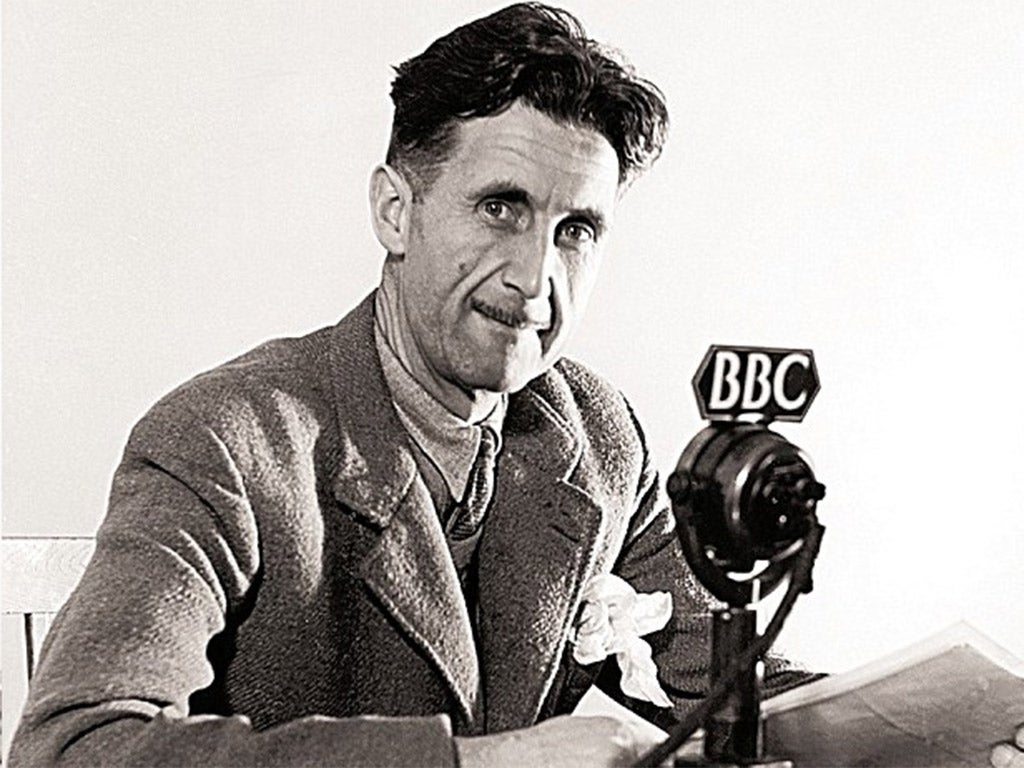

George Orwell (1903-1950)

George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) remain the most widely read leftist books in the world six decades on from their original publication.

These post-war warnings against totalitarianism continue to resonate because the concerns the author raised regarding state propaganda and surveillance as control mechanisms have sadly only become more pertinent with advances in digital technology and the passage of time.

“Orwellian” is an adjective that has been regularly used of late to criticise Donald Trump’s attempt to discredit critical media outlets with the newspeak phrase “fake news” – his Counsellor Kellyanne Conway’s ”alternative facts” is even closer – while everyone knows his coinages ”Big Brother”, “thought police”, “doublethink” and “Room 101”.

As well as the Cassandra of dystopia, Orwell was a thoughtful observer of urban poverty and unemployment in works like Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) and The Road to Wigan Pier (1937), speaking of his “hatred of oppression” in the latter, a passion that saw him volunteer for the Spanish Civil War to oppose Franco’s fascists.

Richard Llewllyn (1906-1983)

Like Steinbeck, the Welsh novelist benefited from a John Ford adaptation of his work, the Western director filming Llewllyn’s 1939 book How Green Was My Valley in 1941 and raising its profile when it won the Best Picture from under the nose of Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, now routinely voted the greatest film of all time.

That novel depicted the lives of coal miners in the Valleys of South Wales, movingly contrasting the narrator’s nostalgia for a Victorian childhood of home cooking and hymns, genteel poverty and first love among the daffodils, with the horrific peril of life below ground – a subject that unites him with Zola.

“For hour after sweating hour, bent double, standing straight only when we were flat on our backs, we worked down there, with the dust of coal settling on us with a light touch that you could feel, as though the coal was putting fingers on you to warn you that he was only feeling you, now, but he would have you down there, underneath him, one day soon when you were looking the other way.”

The great American folk singer Paul Robeson, “the Samson of Song” and an international flag-bearer for socialism, would take the cause of Welsh coal miners to his heart and appeared in a British film examining their plight in 1940, The Proud Valley, campaigning for safer working conditions and fairer wages from pit owners.

How Green Was My Valley’s themes would also resonate across the Atlantic in the coal fields of Appalachia where Kentucky country singer Merle Travis was writing songs like “Dark as the Dungeon” and “Sixteen Tons”, odes to working men toiling in the black stuff.

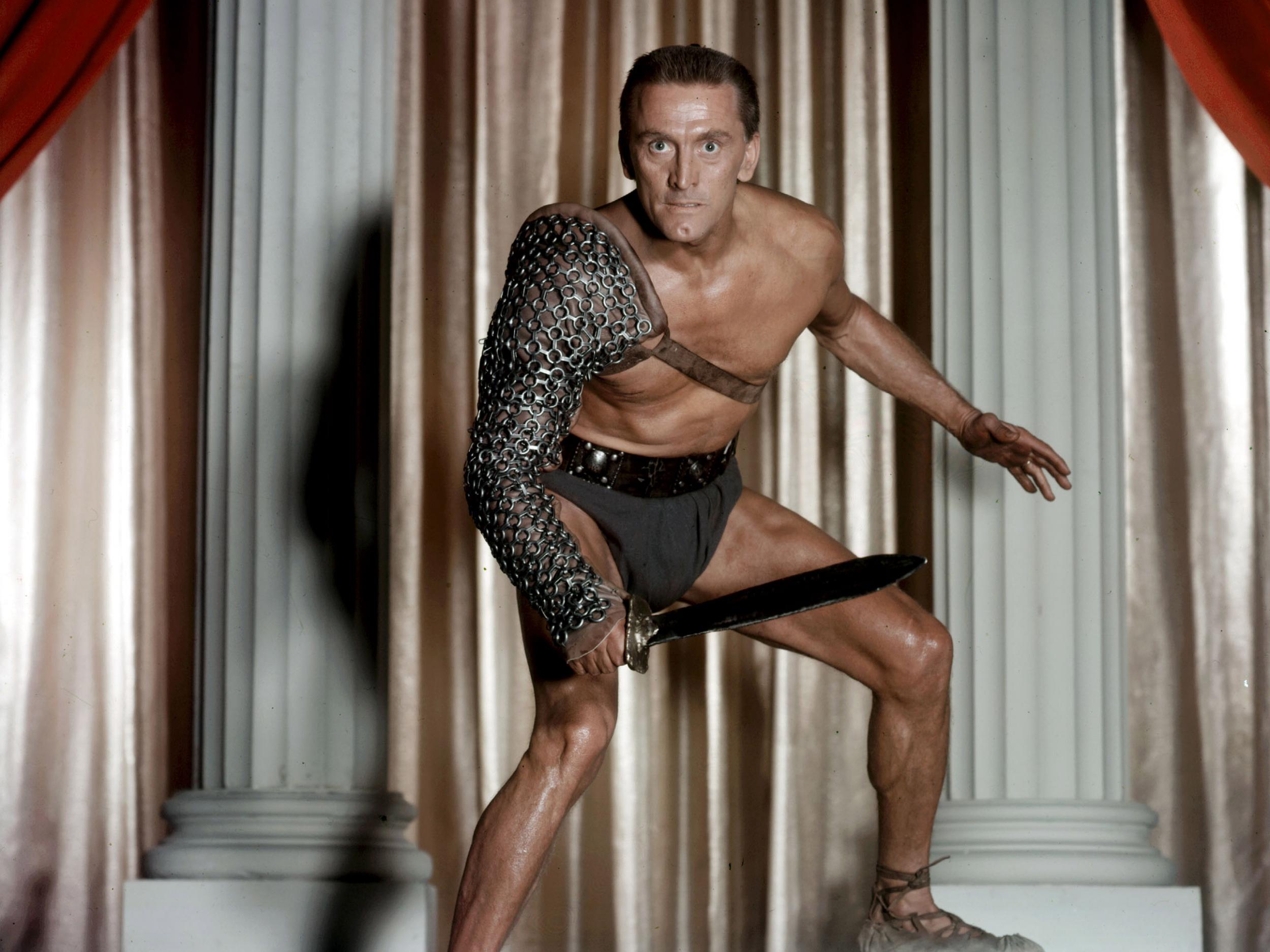

Dalton Trumbo (1905-1976)

A hugely prolific screenwriter known for his personal flamboyance, Trumbo’s career came to be defined when he and his fellow members of the ”Hollywood Ten” were persecuted by Senator Joseph McCarthy over their Communist sympathies.

A witch hunt conducted at the height of Cold War "Red Scare" paranoia, Trumbo and several of his colleagues were blacklisted to prevent alleged leftist infiltration of the studio system. Ironically, this just meant he wrote more as a matter of financial necessity, adopting an array of pseudonyms to get films made from his scripts.

His name returned to the opening credits on Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960) at the insistence of star Kirk Douglas, a film based on Howard Fast’s novel (he too hauled before the House Un-American Activities Committee) about a slave who stands up to the might of the Roman Empire – a perfect David-and-Goliath allegory for the individual versus the system.

Trumbo was nothing if not versatile, putting his pacificism aside in the Second World War to write Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944), contributing to Roman Holiday (1953) and The Brave One (1956) and writing Otto Preminger’s Exodus (1960), an epic about the founding of Israel.

He was also an admired novelist, writing the social realist work Eclipse (1935) during the Great Depression – based on his youth among the fruit orchards of Grand Junction, Colorado – and the devastating anti-war novel Johnny Got His Gun (1939).

Gabriel Garcia Marquez (1927-2014)

A leading light of Latin American culture, the Colombian author of One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967) and Love in the Time of Cholera (1985) is credited with inventing magic realism but his flights of fancy were always grounded in everyday experience, stressing that reality was “a material just as hard as wood”.

The Nobel Prize winner – a former journalist in Bogota and Venezuela known for his reporting during the brutal riots of “La Violencia” between 1948 and 1958 – used his international fame to denounce right-wing dictatorships, becoming an outspoken critic of Chilean strongman president Augusto Pinochet.

Marquez was also a close friend and unwavering supporter of Cuban leader Fidel Castro, the pair bonding over seafood and literature.

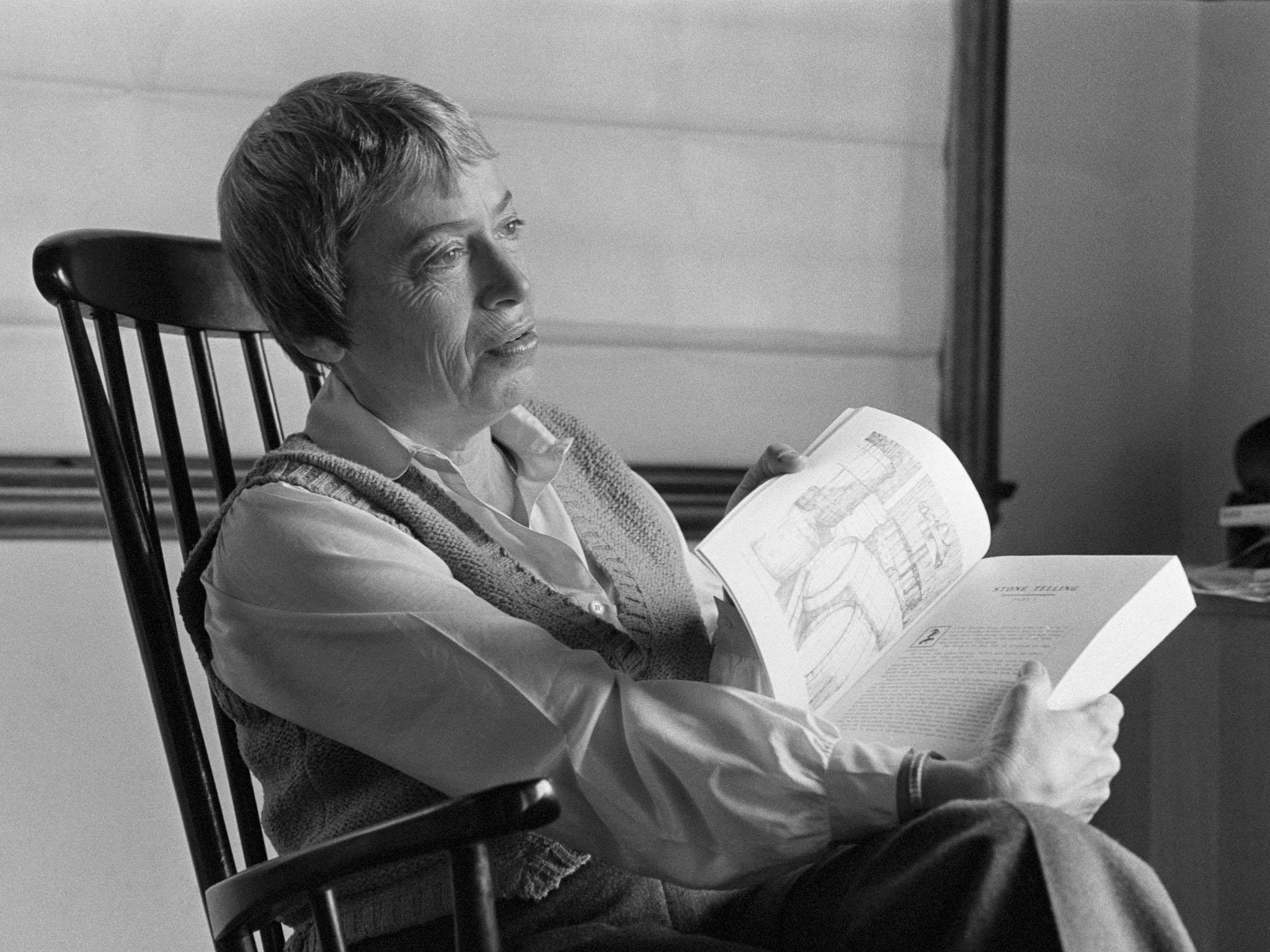

Ursula K Le Guin (1929-2018)

This admired science fiction writer and environmentalist, who passed away in January this year, was hugely prolific but remains best known for her Earthsea fantasy series (1968-2001) and The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), The Dispossessed (1974) and The Word For World is Forest (1976).

Interested in anarchism, the cosmic harmony of Taoism and the overriding universals that unite humanity, Le Guin rejected binary understandings of gender and saw sexuality as a spectrum decades before the mainstream caught up thanks to the efforts of LGBT+ activists.

“The king was pregnant” is a four-word sentence that stunned readers in 1969 and which brilliantly conveys her forthright, challenging manner. Le Guin’s core principle in writing was that anything can happen in the years to come because the future is unwritten. Regimes can tumble, old orthodoxes crumble. Everything is impermanent – an idea simultaneously uplifting and terrifying.

Writing the foreword to Murray Bookchin’s essay collection The Next Revolution in 2015, aged 86, she expressed optimism about the future of the international left:

“Young people, people this society blatantly short-changes and betrays, are looking for intelligent, realistic, long-term thinking: not another ranting ideology, but a practical working hypothesis, a methodology of how to regain control of where we’re going. Achieving that control will require a revolution as powerful, as deeply affecting society as a whole, as the force it wants to harness.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments