Karen McLeod: The beast of Christmas past

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I used to love Christmas until I began a job which meant I would be away for it. Ten years ago I'd started to fly for a living. I'd got my wings, a jaunty navy-blue hat and a rather out-of-date red, white and blue blouse with a matching pleated summer skirt. I had to wear navy high heels and force a natural smile over my face as quick as the clouds could move across the sun. I was an air hostess.

That year, just so I didn't miss out on any of the traditional treats with my family, we began a new tradition: the fake family Christmas Day. We all put on our best clothes, Mum wore dangly reindeer earrings and we got drunk on ginger wine and snowballs with maraschino cherries. I was given free rein of the nut bowl, the family size tubs of Twiglets were drummed out and in the evening there was the traditional endless loop of "Give us a clue" performed in the style of Lionel Blair, until we all felt sick from guessing and went to bed.

Having been pleased with my first faux Christmas, the real thing was to turn out rather more unusual during an eight-day trip to the city of Kampala in Entebbe, south west Africa. I'd asked my old friend Sue if she'd wanted to come and she'd jumped at the chance. We were both excited by a new type of Christmas in a hotel with a pool and bellboys. It would be so unfamiliar, no hope of snow, just intense sunlight and strange birds with pink throats that swooped from the trees above.

It was 80 degrees in the shade on Christmas Day. We were sitting by the pool when a black Father Christmas in a white beard on a sleigh was pulled by hotel staff round the sun loungers. He was sweating in the heat and there were dark marks under his arms in his red jacket, spreading. He was saying, "Ho ho ho and merry Christmas." We sat there in our bikinis looking on, feeling weird, wanting to laugh.

Ask anyone who does shift work or lives abroad and they'll tell you how much Christmas isn't Christmas when you are not surrounded by all the cosy customs. You might as well forget it. So we did forget it, by doing the old airline customary thing of getting drunk. Somewhere during this drunken day we organised a trip to go on safari to Bwindi National Park. Only two months later several British tourists would be killed there with machetes, but we were oblivious.

The six of us consisted of Eric, a French steward and his dad, Flore, a French stewardess and her boyfriend, and me and Sue. We went in a wooden benched van on a six-hour drive down red-earthed, uneven roads. At first it was all jolly as we passed over the Equator. It became less jolly as we began to see the poverty and even less so when we finally got to the park and there was no accommodation for us. They'd sold it all to the highest bidder, but there were dorms where students stayed. We walked in the dark to the dorms and had to pass by a group of guerrillas in their army gear and big dark hobnail boots. They went quiet as we passed. We were given one oil lamp each. I let Sue have the bed with the mosquito net as she was getting bitten more than me and we went to bed, locking the door, but, when all went quiet we could hear the men's boots crunching about outside our window in the gravel.

It wasn't much longer before Sue was out of bed running to the end of the corridor with a funny tummy. She'd taken the lamp with her and I lay under my sheet in the dark, shaking like I used to as a child after a nightmare. Then she screamed and I ran down the corridor to find her sat on the loo, white-faced after confronting a bat which had flown out at her face. We went back to bed. Sue was feeling worse. We locked the door and then, like in a horrible film, we could hear the guerrillas start walking up the corridor with their boots squeaking on the lino. In the light of the gas lamp I could see the door handle turning, I screamed out and Eric's dad came out and started swearing at them. They left, thankfully.

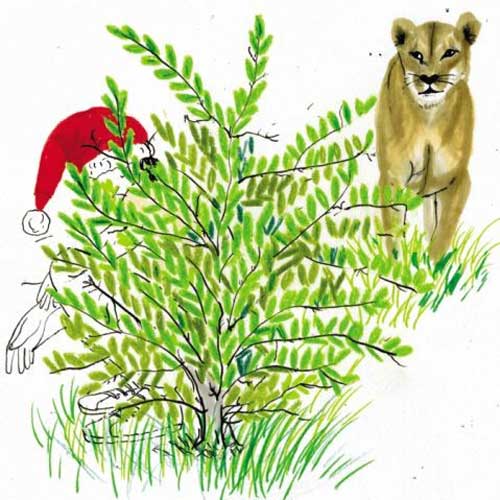

We didn't sleep and were hardly looking forward to the safari the next morning. Sue had a toilet roll in her hand when we boarded the bus. We were in the middle of the bush and at first it was pleasant enough; a few wild boars here, a group of gazelles there. We had almost forgotten the night before when suddenly Sue shouted "STOP!" and jumped out, squatting behind a bush. We all looked out the other side, pretending it wasn't happening. The driver suddenly lifted up his gun and opened his door. He was aiming at a lioness who was padding over in the distance, her nostrils twitching at the smell of Sue's shit. We starting shouting at Sue to get back in and she was saying she couldn't stop. When the lioness was near enough for us to see the flies on her back Sue's buttocks finally clenched and we were out of Africa.

Karen McLeod's debut novel, 'In Search of the Missing Eyelash', is published by Vintage

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments