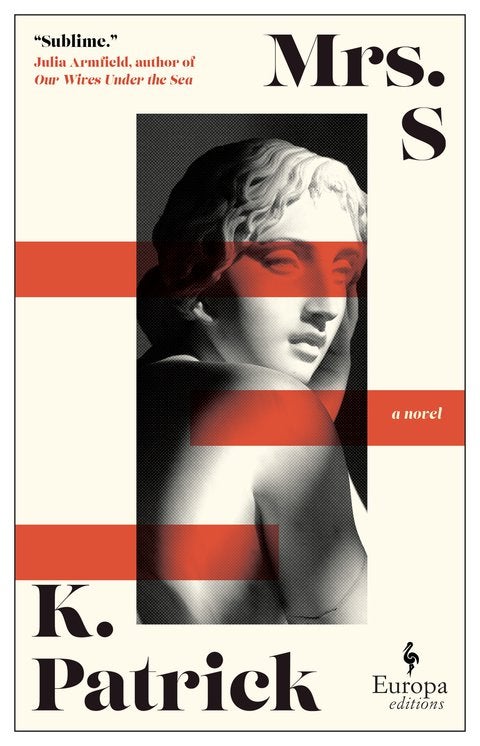

‘I had a pure impulse to write a horny lesbian novel’: K Patrick on their steamy debut, Mrs S

K Patrick’s dazzling debut ‘Mrs S’ won them a place on the prestigious Granta Young British Novelists list. They talk to Helen Brown about gender, sex scenes and the Brontë sisters

The sex?” nods K Patrick, earnestly. “Oh, the sex was the most important part of the book for me. Sapphic literature too often gets trapped behind metaphor so I wanted to be direct. Truthful. I had a very pure impulse to write a horny lesbian novel. Then it became more emotionally complicated…”

The novel in question is the ridiculously steamy Mrs S, a literary debut so striking it scored 38-year-old Patrick a place on Granta’s reliably era-defining list of Best of Young British Novelists, before it was even published. Initial reports incorrectly announced Patrick as “the first non-binary author” to appear on the list. “I don’t know where that came from,” they shrug, “because I’m not non-binary. I’m actually the first trans-masculine person to be on the list. It’s been exhausting. Because I get asked about it a lot. We all know why I’m the first and that’s not a good thing.” Another, wearier shrug. “But it’s also important, so not something I want to shy away from either. Do we need to talk about it?”

I think it might be a good idea to talk about it a bit, later on, because Mrs S shines such a beautiful light into the dark, secret corners of queerness and gender fluidity. It’s set in an exclusive old girls’ boarding school where the pupils ritually kiss the bust of a celebrated Dead Author, who was also a former pupil. Their 22-year-old narrator is a butch, binder-wearing matron who develops an intense crush on the headmaster’s perfumed, fortysomething wife.

Our unnamed narrator is hooked from their first encounter. Gaze clocked, she confesses: “I am discovered, I burn. Like her I stand my ground. Dare her to wave, to give that hand to me […] Loving her will be impossible. There is nothing I can do to stop it.” Later, Mrs S will seek to understand the narrator’s gender just as interviews have sought to define Patrick’s. “It does feel good to be manly,” writes the narrator. “But she doesn’t understand. And yet understanding is everything to her, she cannot see the ego in it, her need to grasp it all, rather than accept what she does not know.”

Patrick, with their elbows on tattooed knees in the glass-walled office of their London publisher, explains that “school appealed to me as a place to interrogate desire, because it’s an environment in which it’s both an apex and actively repressed. I can’t think of many places that deal with so many different types of desire.” They mull on the ways the “complicated, intense” desire of 13-year-old girls feeds into the sexuality of their adult carers. “There’s an atmosphere of surveillance and scrutiny. Girls are always looking, teachers watching. There are very immediate boundaries and imaginations moving beyond them. When I was at school there were rumours that almost everyone was having an affair. You’d hear that the geography teacher was snogging the history teacher. You saw a blind pulled down after English…”

Although they’re wary of giving too much biographical background – “I’ve got parents, I’ve got siblings” – Patrick has a Lancashire accent and says they attended “a relatively remote all-girls school” where the Brontë sisters were educated. They roll their eyes at the way the Brontës have been packaged as brochure heritage when “in fact they had a really bad time at the school. Charlotte used it as the basis for Lowood School in Jane Eyre [which Brontë described as “a cradle of fog and fog-bred pestilence”] where the girls had a terrible time. Their friends all died of typhus. It was an absolute s***hole.”

They shake their head. “I wanted to set Mrs S in an environment that explored class and nostalgia, which is why it’s so important that my narrator is an outsider, from Australia; she doesn’t know all these weird, ancient rules.” They tell me that in most of their own school memories, “I’m on my own. I had a feeling I wasn’t the same as everyone else. Constantly aware of how I was being processed and filtered as a body.” So they found themselves “constantly creating narratives into that vacuum and reacting to the focus on sameness. Receding into fantasy.” They smile, softly, recalling how the Brontës’ “filthy” gothic romances fed into those fantasies. “I thought the sexiest place in the world was a dark castle, nothing else for miles, creepy staircases, closed doors, candlelight, dark eyes…” A chuckle, then a sigh. “When you’re young and queer, you have a really rich fantasy life. Probably the book is born out of all those really intense crushes on teachers I had.”

The pupils at Patrick’s fictional school are only ever defined, en masse, as “The Girls”. Their matron supervises their homework in the classroom used for Latin. Patrick writes: “Lining the walls are pictures of Vesuvius, of cracked Roman busts, curled families preserved in volcanic ash. On the chalkboard behind, an exercise in a grammar of belonging, he or she or we or they, the types of bodies changing the next word. It looks difficult. Pointless.”

After school, Patrick studied French and Spanish at Bristol – so many gendered nouns! – then took various jobs. Although “greengrocer” is the one that comes up most often in profiles, they tell me that they did “the usual things writers tend to do. I did some copywriting. Wrote children’s books.” So they were honing their craft, even if they were glad they held off writing their first poems, short stories and debut novel until their thirties. “This kind of writing,” they tell me, “was a very secret thing, embarrassing to admit to, which is why I waited until I could take myself seriously – although I still don’t take myself very seriously. I have to work on not automatically self-deprecating when people ask me questions.”

This kind of writing was a very secret thing, embarrassing to admit to, which is why I waited until I could take myself seriously

In their early thirties, Patrick did a masters in creative writing at Glasgow University and was buoyed by the enthusiastic support of her tutor, award-winning poet Sophie Collins. When Collins read Patrick’s poetic work – simultaneously straightforward and elusive – she advised her student to enter some competitions. “I would never have done that otherwise,” they smile, “but just before the pandemic I sent a couple of short stories and they did really well. I’ve had some poems published and now this. It’s all been really rapid-fire, which is good because I’m quite an impatient person!”

They tell me that they write best at dawn, on their mobile phone, and scroll through notes for Mrs S for me to see. They explain that they had “very specific conditions” for writing that mostly involved “being flat in a bed, under a blanket, so I can be out of my body and not thinking about my physical form because that can really get in the way of my thinking. It’s really intense.”

Although we’re both uncomfortable discussing the topic – Patrick is protective of their privacy and I don’t want to pry too far on a volatile issue – this is when I ask Patrick to describe what being trans-masculine means to them. “God. It shouldn’t have to mean anything, should it? If you didn’t have to write about me, I wouldn’t have to explain it, would I?” I nod and wince, remembering the line about Mrs S’s egotistical need for understanding. But Patrick is generous with me. “OK. It means that I hold lots of things at once. I feel clear that there are parts of me that feel more masculine and that’s quite a direct feeling. I still feel like neither. I wouldn’t want to be anybody but myself. It’s a hard thing to explain, isn’t it. It’s different for everybody, and somebody else who feels the same way might not identify as trans-masc…”

They also compare the focus others place on their body with “being the only sober person at a party. People are always asking why you’re not drinking, even though it doesn’t affect them. People have so much fear and insecurity about the sense that they might not understand the world any more, and yet this is stuff that has always been there.” A pause. Patrick collects themselves. “If you told me something about how you felt yourself, then I would just believe you rather than argue with you. It’s very self-centred.”

Also, we don’t ask straight, white men to discuss their relationships with their bodies, do we? They snort. “Your average Stone Roses fan would have a panic attack!” They laugh and raise tanned palms. “It’s all stupid, and it’s all really important. That’s why I try not to be precious when it comes to talking about it. But it’s hard when people take it so literally and forget that the most important thing about feeling trans is that it’s this thing that’s in flux. Labels ask you to put an end to something that might feel quite open-ended.”

They look back on a teenage experience in which – though there were no books like Mrs S to connect with – their identity was “protected by secrecy, and now I have the confidence to assert who I am, even if that identity is blurred and between lines. I know things don’t have to make sense to other people for them to make sense to me.” They suspect it “must be overwhelming to feel like I did for kids who are 13 today, reading awful stuff in the press. It must be f***ing horrific to have all these words and terminology thrown at you when those words are not treated with any respect.” They also note that the need to find labels as early as possible “can be a problem when people aren’t relaxed enough to let people come to their own conclusions”.

As a person who’s spent decades “bumping up against language in a way that’s quite frustrating”, Patrick found sex writing surprisingly liberating. “I had to find a form that would hold on to it properly. I’m interested in the way words can release and hold on to the body. The more I think about it now, the more I find that language is a place where sex can be transcendent. I found I was adding, not reducing. I could slow down, add detail, collapse the self a bit.”

I’m interested in the way words can release and hold on to the body

So after the sultry poetry of longing, Patrick delivers explicit detail of their lovers’ sexual encounters. When I tell them my gay friends found the scenes a great riposte to the boorish old hetero question of “what do lesbians actually DO in bed?” they nod. “This must be a rebellion against that on some level. Because we all grew up with that question. For me, the writing of good sex scenes is all about rhythm. To get mine right, I spent a lot of time copying out other really good sex scenes. Especially stuff by Robert Glück. He writes the best sex ever in Margery Kempe [1994].”

One of Patrick’s most erotic scenes finds their matron and Mrs S taking a swim in a river. “If I could choose a different body, I would choose this water,” says the narrator. Today Patrick tells me that “that involvement with nature feels like a very trans sensibility, because of the hyper-attunement to the body. You’re putting your body into a context where it feels freer and looser. And swimming is so contentious for the trans body because there’s so much visibility. You’re on display in a way you can’t control. But then when you’re submerged, it’s like kind of transcending, birthing, the form is lost.”

So does Patrick swim? They shake a rueful head. “I’m a terrible swimmer. But for my birthday I bought myself a wetsuit, so I’m going to get it on and get into the water.” They now live on the coast of the Isle of Lewis with their partner, and they want to immerse themselves in everything that landscape has to offer. “At the moment my body is quite a heavy thing to carry,” they say. “So I’m hoping the water helps with that. It may be four strokes to begin with, but I’m still excited. I’m hoping for my mind to move out of my body, for a new kind of joy.”

‘Mrs S’ is out now, published by 4th Estate

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments