Books of the month: From Frankie Boyle’s Meantime to Jessica Andrews’ Milk Teeth

Martin Chilton reviews six of the July’s biggest releases for our monthly column

There are eight pages listed under “misogyny” in the index of Mary Honeyball’s biography Edith Summerskill: The Life and Times of a Pioneering Feminist Labour MP (Bloomsbury). Dr Edith, as she was known, served in Clement Attlee’s post-war government and helped build the welfare state. She was a pioneering campaigner for women’s rights, yet often faced derision from chauvinist MPs. In 1939, more than 7,000 Britons were killed on the roads, 1,000 of them children – yet Summerskill was laughed at by the Tory front bench when, in 1940, she suggested that those found guilty of drink-driving should face “severe penalties”.

Summerskill also campaigned to improve conditions for prisoners – a subject that comes into two revealing books out this month: Dr Shahed Yousaf’s Stitched Up (reviewed in full below) and Dr Ben Cave’s What We Fear Most: Reflections on a Life in Forensic Psychiatry (Seven Dials). Cave, who says working at Campsmoor jail was more challenging than anywhere else in his career, admits that “the amount of severe mental illness in prisons never ceases to amaze me”.

Among the most impressive historical fiction out this July is Frances Quinn’s That Bonesetter Woman (Simon & Schuster), based on a real story about two sisters in Georgian London, one who is desperate to be a female bonesetter and the other who is a determined social climber. One of the standout novels of the month is Gabrielle Zevin’s Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow (Vintage). Set in the world of gaming, it is a wildly imaginative and touching tale of friendship and the volatile nature of creative collaboration. Other July highlights are Camilla Grudova’s Children of Paradise (Atlantic Books), about a cleaner in an old Edinburgh cinema; Sadie Jones’s Amy & Lan (Chatto & Windus) a moving story of two children growing up on a communal farm in the west country and Rebecca Wait’s I’m Sorry You Feel That Way (Riverrun), an enjoyably bittersweet novel about a dysfunctional modern family.

Twentysomethings are well represented in 21st-century fiction, of course, but if you are open to a salient, imaginative view of the landscape of old age, then Jane Campbell’s debut short story collection Cat Brushing (Riverrun) – coming in the year the author turns 80 – is a recommended read. I particularly liked the unexpectedly morbid tale “The Scratch”.

Finally, my music book of the month is Barbara Charone’s wonderfully vivid memoir Access All Areas: A Backstage Pass Through 50 Years of Music and Culture (White Rabbit). Charone, a respected publicist and former music writer, offers up entertaining tales and insights into stars such as Madonna, Keith Richards, Dave Grohl and Elvis Costello (who writes a warm foreword for the book). The chapters on her work as a music journalist in the 1970s are particularly riveting, including her funny dealings with Rod Stewart and her coke-fuelled friendship with the late, great Lowell George of Little Feat. Access All Areas is a captivating read and will leave you in no doubt why Madonna told Charone, “You f***in’ rule.”

Novels by Frankie Boyle, Jessica Andrews, Lillian Fishman and Selby Wynn Schwartz, along with non-fiction by Markiyan Kamysh and Dr Shahed Yousaf are reviewed in full below.

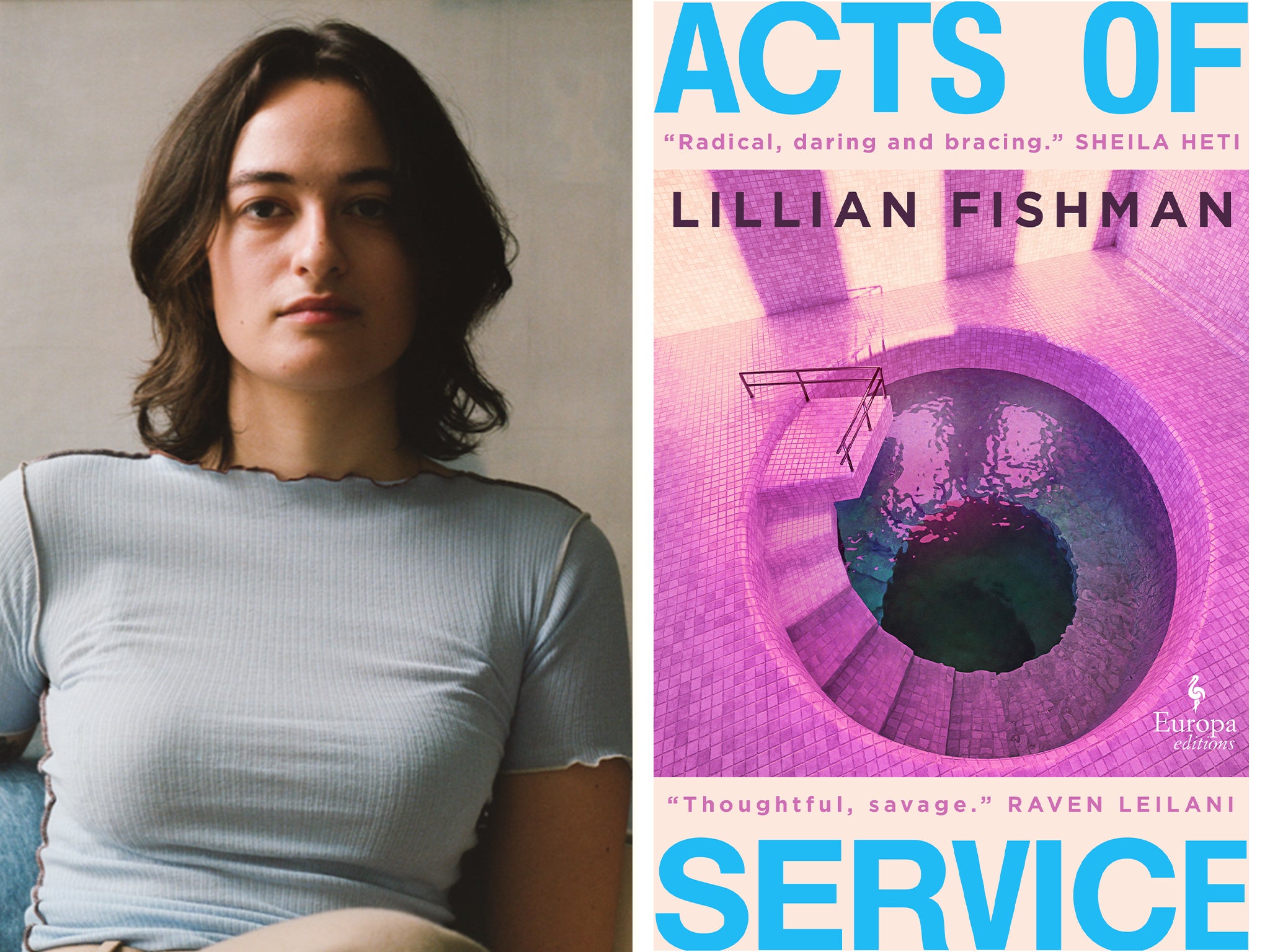

Acts of Service by Lillian Fishman ★★★★☆

“To burn with desire and keep quiet about it is the greatest punishment we can bring on ourselves,” remarked poet Federico García Lorca. In her formidable debut novel Acts of Service, Lillian Fishman conjures, in narrator Eve, a protagonist who stays anything but quiet about the “overwhelming, murderous desire” that consumes her during a complicated love triangle.

Bored with her queer relationship with a nurse called Romi, 27-year-old Brooklyn-based Eve posts selfie nudes online. She is soon lured into a three-way affair with shy artist Olivia and charismatic financier Nathan. In elegant and philosophical prose, Fishman explores the complexities and power of this dangerous pleasure-seeking liaison.

Capitalism, and one’s personal complicity within it, is an intriguing theme in the book. Olivia and Nathan work together, allowing the novel to explore the weird power dynamics of an affair between co-workers, especially in a boss-employee situation.

Fishman also has interesting things to say about the problems of a bisexual woman seemingly wanting to be valued sexually and physically by a dubious man. And Nathan, who cheerfully admits he is a “natural liar”, is a supremely self-gratifying, over-confident man. “Before I met him I would have said his type had gone entirely out of style. Who had patience anymore for cold, educated white men in well-appointed rooms?” Eve tells herself. You can puzzle out for yourself why she melts into his authority.

Ultimately, Eve begins to fear that she is a mere “prop” in the triangle and that they are “privately sadistic” about her when they chat in secret. Things come to a head when Nathan is caught in a legal battle over his workplace behaviour.

Acts of Service is a potent, erotic and challenging novel, one that deals with the thirstiness and fickleness of full-blown desire. It’s another reminder of the eternal elusiveness of certainty when it comes to love.

Acts of Service by Lillian Fishman is published by Europa Editions on 7 July, £12.99

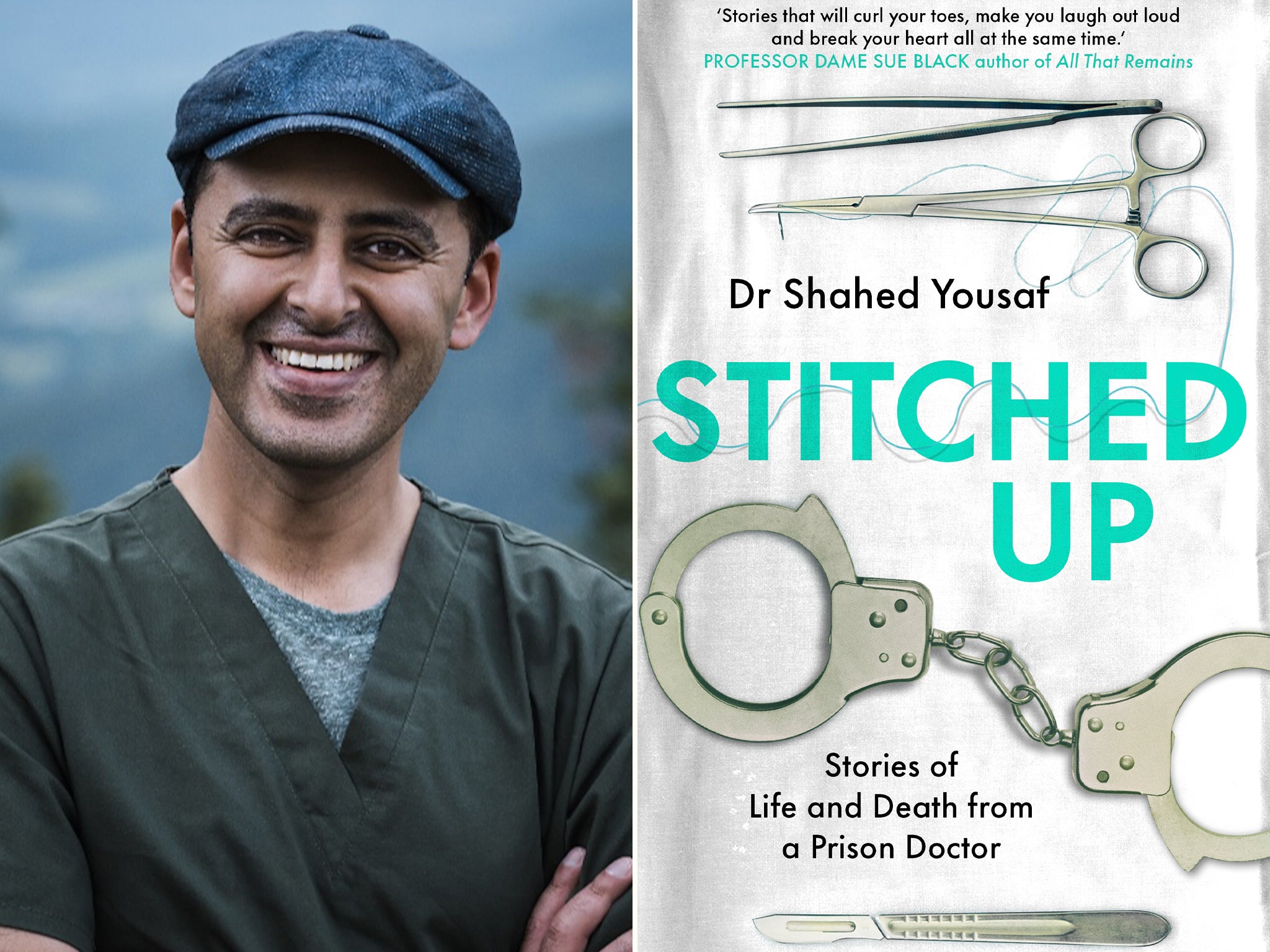

Stitched Up: Stories of Life and Death from a Prison Doctor by Dr Shahed Yousaf ★★★☆☆

When he was secretary of state for justice in 2012, Chris Grayling boasted that he would stop our jails “being like holiday camps”. According to Dr Shahed Yousaf, a GP who grew up in Birmingham and who has worked in prisons for a decade, “this false narrative still prevails”. Stitched Up, Yousaf’s harrowing account of what it’s like to treat the incarcerated, challenges this image, portraying prisons as breeding grounds for crime, radicalisation, substance misuse, mental health problems, brutality, self-harm, rape, suicide and murder.

Yousaf discusses why it was so damaging and short-sighted of Grayling, a Conservative MP in leafy Surrey, to try to ban books being sent to prisons. There are shameful illiteracy rates in our jails, with the reading age of approximately 50 per cent of inmates in England and Wales being poorer than an average 11-year-old. Yousaf cites the tragi-comic example of one prisoner who could not read medical labels. He did not realise he had to swallow the paracetamol tablets he was given for his sore elbow and instead bandaged them to the outside of his limb.

As well as offering gruesome insights into the degrading conditions in jails – the all-pervasive muggy stench of the buildings; hungry prisoners reliant on meals so stinky that the doctor holds his breath when he walks past food trolleys – he also details the strange minutiae of his working life, including the fact that he’s not allowed to prescribe coal tar shampoo, because some prisoners dry it on paper and smoke it. It is sometimes hard to avoid feeling a little voyeuristic reading about some of Yousaf’s more horrendous cases, especially the horrible one of the “autocannibal” inmate who changed his name by deed poll to Mr Freddie Mercury.

Britain’s prison population has risen by 70 per cent in the 21st century and reoffending rates are at a record high. There is a crisis in these institutions over mental health provision. As well as being an eye-opening memoir, Stitched Up is a timely call to action.

Stitched Up: Stories of Life and Death from a Prison Doctor by Dr Shahed Yousaf is published by Bantam Press on 7 July, £16.99

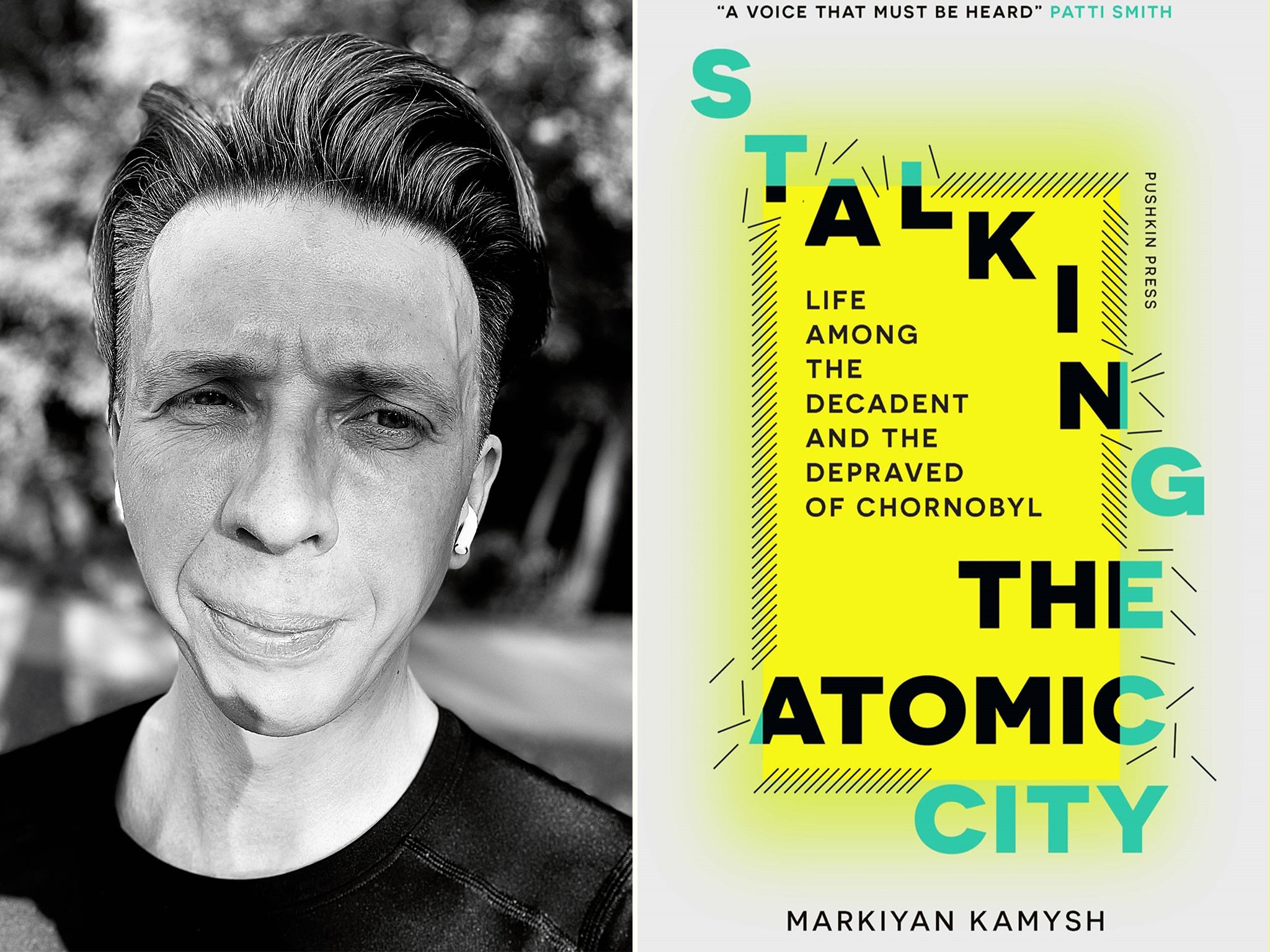

In Stalking the Atomic City: Life Among the Decadent and the Depraved of Chornobyl by Markiyan Kamysh ★★★☆☆

“Normal people have no business in a radioactive dump,” writes Ukrainian Markiyan Kamysh, a man who has made more than 15 illegal sorties into the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone.

In Stalking the Atomic City: Life Among the Decadent and the Depraved of Chornobyl (translated by Hanna Leliv and Reilly Costigan-Humes), he provides an unforgettable insight into a bleak landscape that attracts “drug addicts, daredevils, deserters, looters and fugitives”.

The 1,000-square-mile Zone (about the size of Luxembourg), which was devastated by the nuclear disaster of April 1986, remains a wreck. If it’s not enough to be stalked by wolves, ravenous jackals and wild dogs, you can always enjoy the swamps that teem with clouds of mosquitoes, or drink from the rivers that are full of tainted water and leeches. It’s a place that appeals only to radiation fetishists, macho thrill-seekers and armed looters who are making money off contaminated scrap. Kamysh, who claims to enjoy the mystery of it all and says he finds a “peace” among all the abandonment, certainly cuts an odd figure. However, he is droll about his own character, admitting he dresses “like an angry bum from Pol Pot’s guerrilla unit”.

The desolation of the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone (the Ukrainian spelling) is brought home in the 20 stark black and white photographs dotted throughout the book. Sadly, there are no snaps of the slogans Kamysh spots during his genuinely eye-opening “travelogue”: ‘WE’LL BEAT YOU, REAGAN!’ and ‘PUTIN IS A DOG’.

For all the shocking descriptions of man-made wasteland, it is the grimly fascinating insights into the reckless characters who venture into such a toxic landscape that makes Stalking the Atomic City a memorable read. Then again, perhaps a future as “residents of the apocalypse” is what awaits all the human race, and the book is simply a preview brochure.

In Stalking the Atomic City: Life Among the Decadent and the Depraved of Chornobyl by Markiyan Kamysh is published by Pushkin Press on 7 July, £12.99

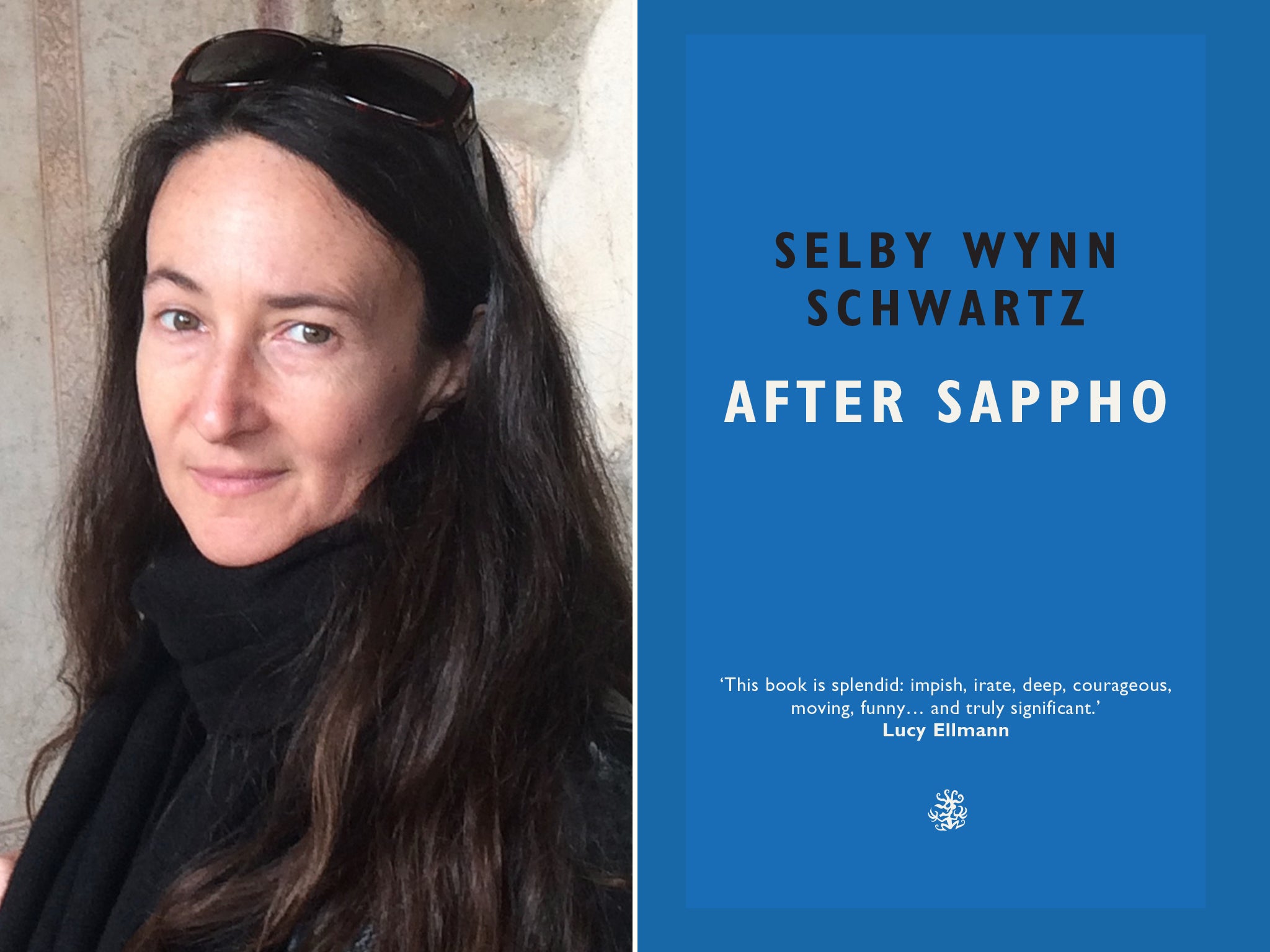

After Sappho by Selby Wynn Schwartz ★★★★☆

In 1897, the men at Cambridge University roared with delight, lit fireworks and hung an effigy of a Girton College girl astride her bicycle after winning a vote to ban women from taking full degrees. The story is just one example from After Sappho of how the women of the period – who dared to challenge what men had prescribed as their inevitable, squashed destinies – were met with derision and hostility.

Although author Selby Wynn Schwartz neatly skewers the ludicrous patriarchal figures of the time – including the obsessive homophobe MP Noel Pemberton and Lord Abermarle (a man who supposedly said “I’ve never heard of this Greek chap called Clitoris they are all talking of nowadays” during the defamation trial of actress Maud Allan, then starring in Oscar Wilde’s controversial play Salome) – the real focus of After Sappho is on trailblazing women.

The book is a hybrid of fiction and nonfiction, told in a series of fragmentary, cascading vignettes, with hundreds of voices and interlinked stories. The characters, turn-of-the-century writers, artists and feminists, in Europe and the UK, famous and unsung, are vividly brought to life. The featured characters include Virginia Woolf, Isadora Duncan, Eleonora Duse, Lina Poletti, Natalie Barney and Josephine Baker. Some of the best entries are about actress Sarah Bernhardt, a wild woman who kept exotic pets, including an alligator that died after drinking too much champagne.

The book merges history, myth and politics in an enthralling blend and is underpinned by a droll historical wit (“we had all known too many Phaons, with their paltry charms”). Above all, the book is a gorgeous celebration of those pioneering thinkers who rejected docility and self-abnegation in favour of finding their true selves and being more than just “little dolls who danced for the pleasure of their husbands and annihilated themselves”. This sparkling, imaginative gem skillfully conveys just why this cast of women were drawn to the poems and fragments of Sappho.

After Sappho by Selby Wynn Schwartz is published by Galley Beggar Press on 15 July, £9.99

Milk Teeth by Jessica Andrews ★★★★☆

Jessica Andrews has followed up her Portico Prize-winning debut novel Saltwater with the excellent Milk Teeth, a sharp and beguiling love story set in London, the northeast, Paris and Barcelona.

The novel opens in Peckham and flips between the unnamed protagonist’s present and past relationships as she attempts to make sense of what she wants from life and why she has spent so much time pushing down her own needs and wants. “I am trying to live more easily, to become someone softer,” she says, admitting she has run away to places, including to work in Paris as a nanny, to escape her own frantic mind. “Worry settles in my stomach like sand,” she says, in a simple, yet potent simile.

Milk Teeth is, in part, a stirring story of what it’s like to grow up as a working-class girl in the northeast. Sunderland-born Andrews sets some scenes in Durham and in Bishop Auckland – known as “Bish Vegas”, “on account of the women spilling out of the pubs in their sequined dresses and stilettos, and the men with their short-sleeved shirts and football tattoos” – and shows why the modern obsessions with body, food and self-image can be so toxic.

The story, which also deals with a fragile father-daughter relationship, a love affair on the brink of collapse and a faltering childhood friendship, is told over 250 pages, in 98 short, sharp chapters. The flashbacks scenes are handled with aplomb. Andrews explores the pressures on her “heroine” to having her sense of self-worth defined by men – let alone combatting a world in which “stray hands and lingering eyes”, leering teachers or men who expose themselves in public seem to be the sadly predictable norm. It’s unsurprising that the protagonist is left besieged by a “scrabbling, choking feeling that is always in me” and is always ready to run away.

To rescue a promising but crumbling relationship, she moves to Spain. It is there she finally starts to work out what she wants from life and why she does not need to deny herself good things. These Spanish sections, languid, elegantly written and dripping with a rich emotional humidity, are deeply engrossing. Milk Teeth is a transporting, gorgeous novel.

Milk Teeth by Jessica Andrews is published by Sceptre on 21 July, £14.99

Meantime by Frankie Boyle ★★★★☆

When Marina Katos’s body is discovered in Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Park, her best friend Felix McAveety is brought in for questioning. Even in a drug-induced haze, Felix is certain that the police aren’t fit to find the murderer. “I’d never really liked the police: people have complex problems, and maybe the best person to solve them isn’t a guy with two GCSEs and a stick,” he later reflects.

Felix, the protagonist in Frankie Boyle’s cranked-up, zany crime noir, decides to solve the killing for himself. Along the way he enlists the help of a cast of eccentrics, including a dying crime novelist called Jane Pickford, a splendid character.

Boyle’s debut novel, set in the aftermath of the Scottish independence referendum, in a Glasgow that is now “like some kind of skaghead Whisky Galore”, is ferociously energetic and blazes with the sort of edgy, near-the-knuckle humour that has made Boyle such a popular comedian and television host. His fans will adore the book. Anyone sensitive about jokes concerning death, w***ing, Catholicism, Burns Nights, 9/11, do-gooders, date rapists, c***s in Dumfries and sneezing “cum faces”, should probably look elsewhere for their summer crime thriller fix. And the book should carry a warning sticker for Mumford and Sons fans, unlikely to enjoy a joke about getting a w*** at Glastonbury.

Boyle, who studied English Literature at Sussex University, is clearly a fan of the crime thriller and has improvised his own thing with the genre. The main character is a walking stream of consciousness, constantly veering off at tangents, about everything from the contradictions of capitalism to Ella Fitzgerald’s vocal stylistics. I liked Boyle’s clever descriptions (“his bike was too small and made him look like a bear escaping from a circus”) more than the shock-value ones (“his face looked like a collage made from elephant vaginas”) and his characterisations of the sweaty underbelly of Glasgow lowlife are sometimes hilarious. Who would want to step into a Wetherspoons that, in the evening, “took on the atmosphere of pre-drinks for a dogfight”?

There is no doubt that Boyle can be very funny – and who can blame him for recycling sharp lines from his stand-up career, such as “my body looked like a dropped lasagne”? – but along with entertaining jokes about bungalows, death and fleshy politicians, come moments where the book does sometimes feel like a print version of one of the end-of-show monologues on his television show Frankie Boyle’s New World Order, one where perhaps a judicious editor’s red pen would have helped.

That said, Boyle is a spiky, challenging social commentator and his philosophising seasons the novel nicely. The book is packed with thought-provoking reflections, on everything from why television and bar jobs are similar (“both are pretending to be the friend of the people you were actually tranquilising”), to the flaws of social media, Britain’s rigged class system, the lack of a modern counterculture and faux individuality. There are also a few good jokes about Huns, thrown in for good measure by Celtic fan Boyle.

Boyle’s fiction debut is genuinely engrossing. There are lots of twists, larger-than-life villains (including Doctor Chong) and a dramatic finale. Meantime succeeds, overall, because Felix McAveety is a transfixing, sharp-witted and slightly horrifying central character. Nothing like Frankie Boyle, of course.

Meantime by Frankie Boyle is published by Baskerville on 21 July, £14.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments