Journalist and novelist Blake Morrison interview: 'As long as I’m writing ... I’m happy’

Journalist and novelist Blake Morrison talks about what made him return to poetry

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

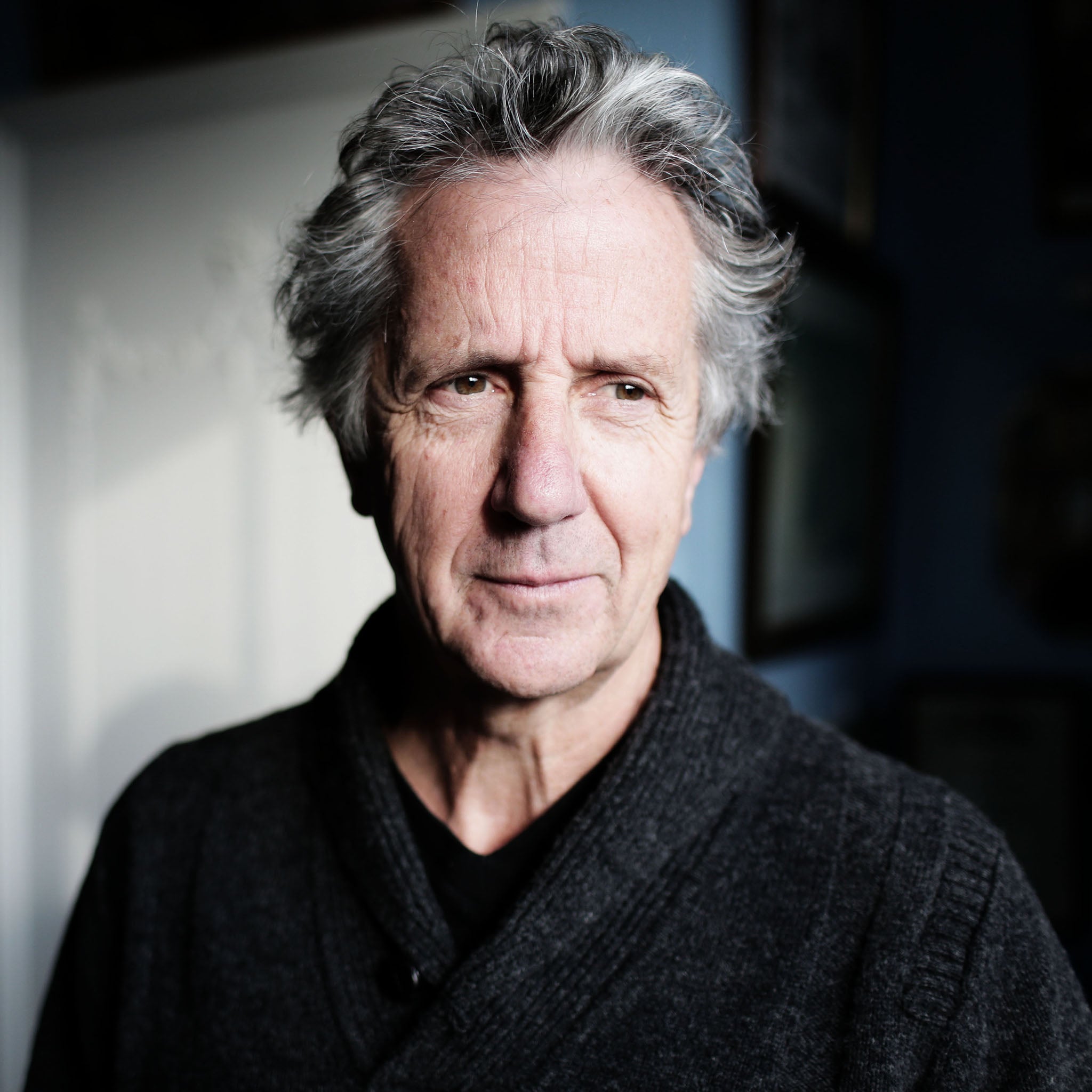

Your support makes all the difference.The professor of Creative Writing at Goldsmiths College, revered journalist, novelist, and godfather of the “narrative non-fiction” genre confesses to feeling nervous about the publication of his new book.

Shingle Street is a collection of poems, Blake Morrison’s first for almost three decades. But for readers with long memories, he was a poet and critic before he was anything else: author of the searing The Ballad of the Yorkshire Ripper and a sharp critical overview of the mid-50s poetry scene, The Movement.

I’ve asked him whether he feels relief – still got the magic! – about writing poetry again. “I wish it felt like magic. Mostly, I feel apprehensive. I’ve been away for so long and there’s a whole generation or two come up in the meantime, and probably the poets they read and they’re influenced by are very different from mine. I feel quite cut off from the poetry world. There’s a whole generation [of poets] who never knew that I even wrote poetry, and if they’d heard of me at all they would have heard of the book about my dad [And When Did You Last See Your Father?]. So there isn’t a simple, joyful, ah! It’s back, I’m back, because you’re a bit nervous about whether you’ve still got it or not.”

He’s definitely still got it. We’re having tea in his book-crammed study. The view from the window is astonishingly leafy, even for south London; barely another building in sight. This could only be a poet’s room, I remark, noting the abundance of slender collections and hefty critical works lining the room.

“No, I think it’s a mixture,” he corrects. “That’s the fiction over there, that’s the poetry and there’s the criticism. You are pointing to the fact that I’ve done a bit of all of them …”

And the plays. “I’ve only ever really adapted plays so I don’t think that counts. But you see, missing from this room is the life writing. Which I have at Goldsmiths, in my office. Quite a large collection now.”

Morrison’s last full poetry book, The Ballad of the Yorkshire Ripper, was published in 1987. But there have been lyrical spurts since then: a Selected with Granta, a pamphlet entitled This Poem... and a sequence on the 400th anniversary of the Pendle witch trials in 2012. Speaking as someone who grew up in the shadow of Pendle Hill, I say, I’m a bit fed up of Yorkshire lads like him and Simon Armitage coming over tackling our witches…

Morrison laughs: “Be careful! Don’t forget, I was born in Burnley and spent my early years in a town that was close to Leigh in Lancashire but geographically in Yorkshire. I’ve got more excuse than Armitage!” He even pronounces it right, “Burn-leh”. We’ll let him off.

So how did the new collection come about? “I suppose for the last five or six years, after a long gap, I started writing poetry again. And a lot of it up in Suffolk. It sounds a bit pretentious, but I find whereas here [London] is more workaday, more prosy, up there I seem to write poetry and … I suppose I wanted to write about the east coast and that part of the world.”

So the title poem is about a real place? “Shingle Street absolutely exists, and isn’t it a great name? It’s a beautiful but ominous place. You really feel the force of the sea there, the way the shingle moves from year to year. There’s the idea of defence, defending the land from invaders. It’s a rich place in its associations and I wanted to explore that a bit.”

![“At times of crisis or distress, it’s poems that people turn to. [Poetry] still has a power to speak to people’s feelings, maybe in a way that fiction, because it works in a longer way, can’t.” (Justin Sutcliffe)](https://static.independent.co.uk/s3fs-public/thumbnails/image/2015/01/30/11/Author_Blake_Morrison3.jpg)

The rhythm of the poem sounds as if you’re trudging down a beach, crunch crunch crunch, it’s got that beat … “Exactly right! I was walking on that beach and this rhythm started through the trudging and the shingle, a certain rhyme that kept coming up, street, feet, neat, and then it was just a matter of time developing that.”

But Shingle Street has a darker side. “There are all sorts of rumours about a terrible catastrophe that happened there during the Second World War. They are just rumours, but the British developed this anti-invasion strategy which included some device of setting the sea on fire with oil. They did experiments with it, and there were rumours of either an experiment that went horribly wrong, or a German invasion that was thwarted. Some terrible conflagration at Shingle Street. That although it’s a cold, wet place, something burnt there on the shore …”

A brief poem about Jimmy Savile, “It Was Good While It Lasted”, seems to recommend reticence on the subject of that other evil Yorkshireman. “It’s not that I think we should ignore paedophilia and Savile,” he insists. “But the responses were either smartarse – ‘everybody always knew’ – or huge piety. And maybe piety is the right reaction, but it’s not as if only he were guilty of abuse of children; it was a whole culture. Jesus, it went way beyond Savile.”

The deft villanelle “Life Writing” takes a semi-jokey look at Morrison’s stock in trade, summing up: “It’s safer telling lies about the dead.” Other poems tramp along the desolate beaches of old age: “Brief heat. Then death. That is the law.” It’s a time for looking back. “Michael Longley said to me, ‘There are only young poets and old poets. There aren’t middle-aged poets.’ Middle-age is your mortgage and your day job and they don’t leave the imagination free for poetry.” Yet it’s a fresh and invigorating collection, too well-crafted to be truly gloomy.

He’s seen the whole “poetry is the new rock and roll” bandwagon come and go a few times, but nevertheless, “At times of crisis or distress, it’s poems that people turn to. [Poetry] still has a power to speak to people’s feelings, maybe in a way that fiction, because it works in a longer way, can’t.” But, good northern lad that he is, he’s pretty pragmatic. “There’s a little bit of your brain that mourns and grieves that you’re not writing poetry, but actually as long as I’m writing something, I’m happy.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments