The Secret Life of John le Carré: A portrait of two literary men having a breakdown

David Cornwell, aka John le Carré, claimed his multiple infidelities were a ‘drug’ for his writing – but the discovery of them sent a planned biography off the rails. Robert McCrum asks: does Adam Sisman’s distressed, fascinating, and mildly vengeful follow-up change anything?

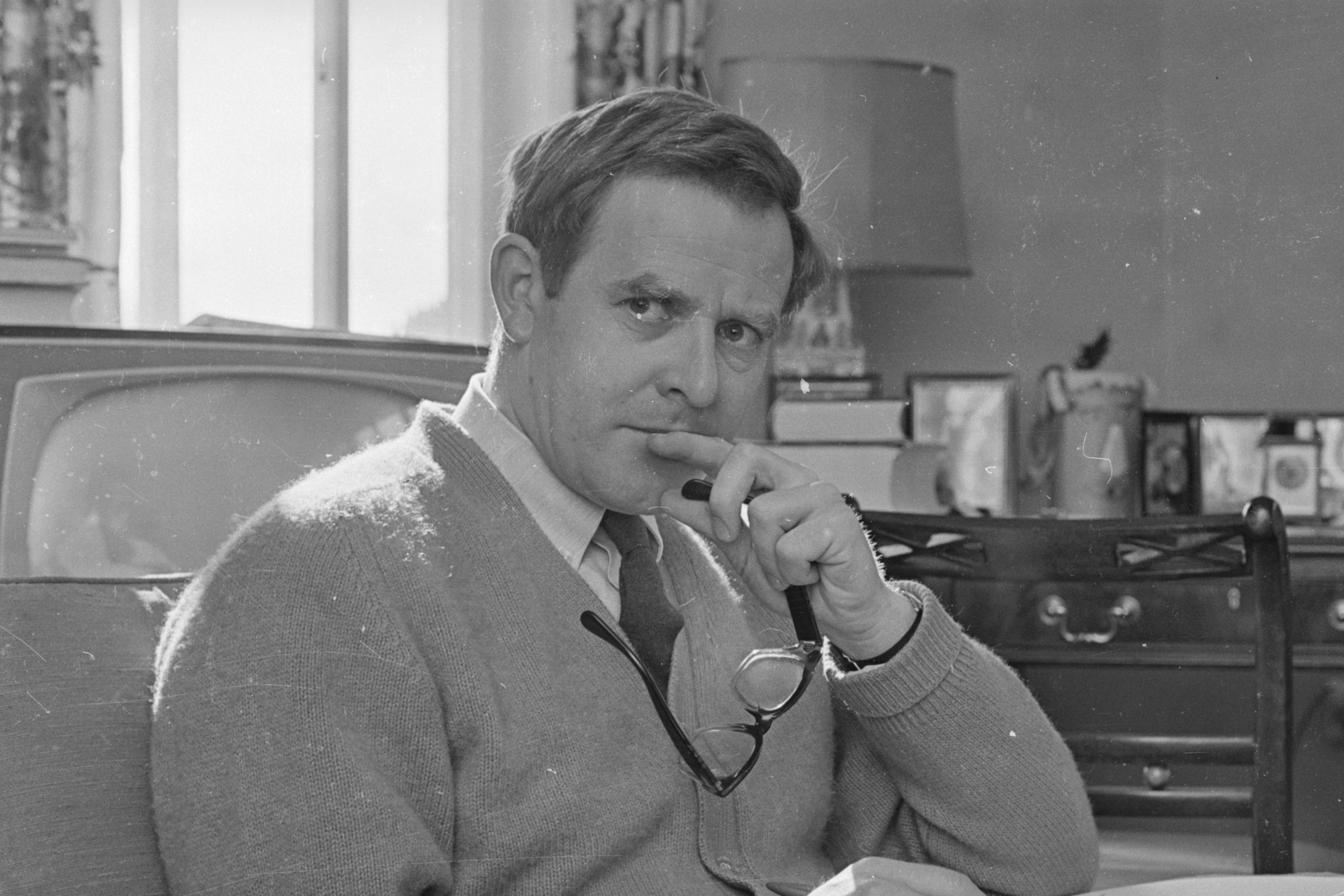

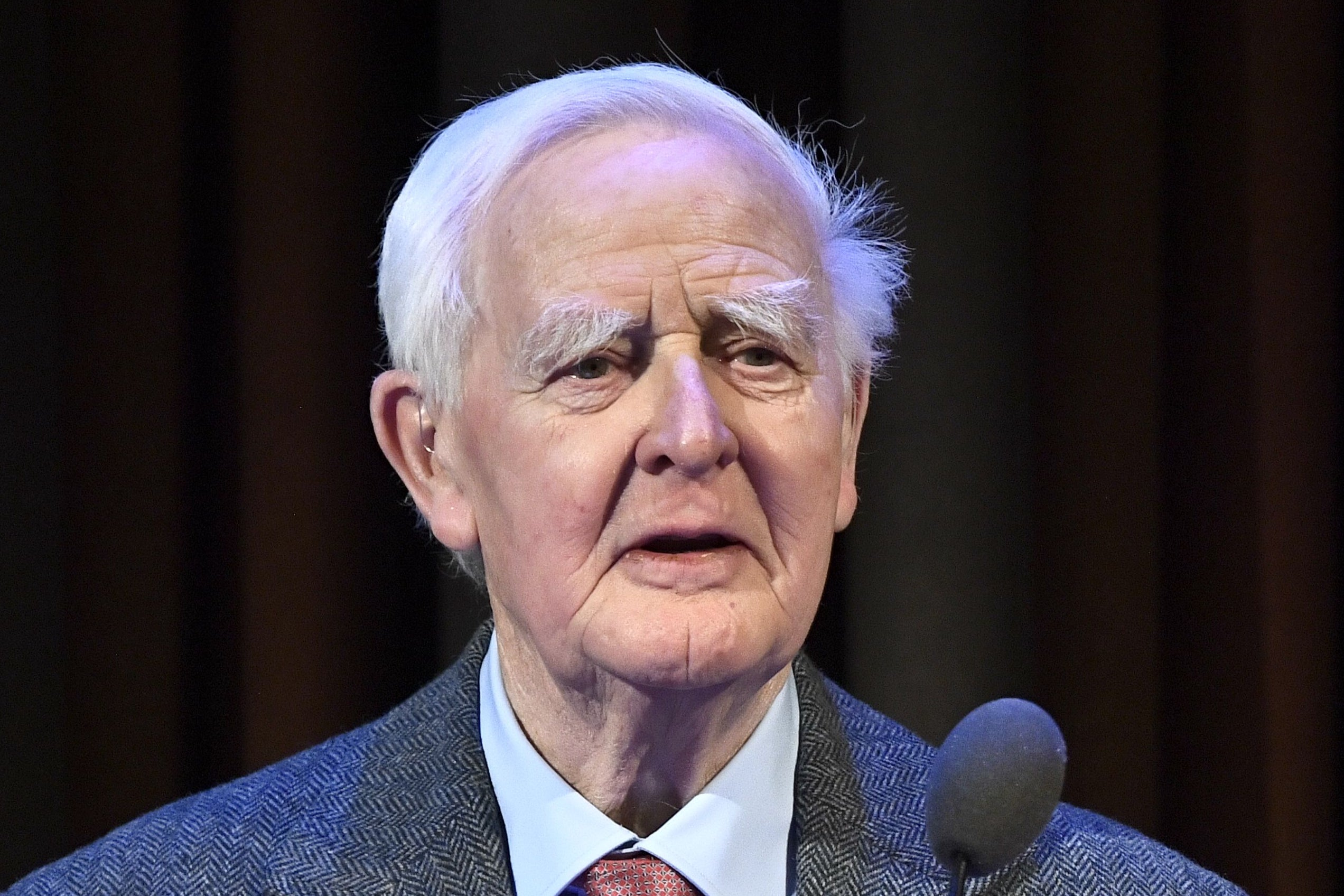

Ever since The Spy Who Came in from the Cold appeared in 1963, John le Carré (aka David Cornwell), has bewitched his readers with contemporary spy novels (Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy; The Honourable Schoolboy; Smiley’s People) that seemed to catch the soul of the age. To some, such as Philip Roth, he was a major English novelist; to others, like Anthony Burgess, a jumped-up thriller writer. Whatever your verdict, there’s no doubt that he policed the mystery of his pseudonymous enigma, with an almost sinister zeal, to remarkable effect. When he began to entertain the idea of a “life”, it was a fair bet that the old magician would ensure it was the cornerstone of his claim on posterity. Dame Fortune, however, had a twist up her sleeve.

The Secret Life of John le Carré is his biographer’s painfully honest and anguished retrospective on his torturous collaboration with a living literary icon, a project that dragged him to the depths. Adam Sisman is the respected author of Boswell’s Presumptuous Task: The Making of the Life of Dr Johnson. He was probably aware of the risks in such a contract. Long before he proposed himself for mission impossible, he must also have known that Le Carré’s alter ego would not freely comply with the merciless audit of life-writing. At least one would-be biographer had been chased off with writs; a second, the writer Robert Harris, was wooed, then frozen out. In fairness, Sisman’s overtures seemed to augur well.

In May 2010, Sisman sent a letter to John le Carré offering his services as a biographer, a letter he probably regrets. In response, the celebrated recluse seemed nothing but charm itself. He flattered Sisman, dropped his guard (“I am very divided about how to respond”), confessed a “messy private life” and closed with a tempting coda, “I would wish you to write without constraints”. A fateful agreement followed. Both Cornwell and Sisman believed that their desires had been fulfilled. The writer was confident in his choice; the biographer celebrated a literary coup. At this stage in their mutual courtship, Sisman was on best behaviour, while Cornwell’s famous charm was in seduction mode. He had, writes Sisman, “the ability to make people love him even when they knew that they shouldn’t”.

Then came the first snag – Cornwell’s marriage to his second wife Jane, an alliance he described as “more monogamous than most couples”. Sisman already knew that his subject was serially unfaithful, and the subject of Cornwell’s adultery weighed heavily with him. “Our relations became strained,” he writes. The upshot was some mediation by Cornwell’s eldest son, and a pie-in-the-sky proposal that Sisman should keep “a secret annexe” for publication after Cornwell and his wife were dead, as they now are. Neither side was reconciled. Sisman made it clear, in his introduction to John Le Carré: the Biography (2015), that he had been leant on; he also advertised his ambition “to publish a revised and updated version” at some unspecified future moment.

It’s here and now that this second volume, The Secret Life, dubbed by Sisman “what was left out”, appears as the unhappy coda to a volume that was once blessed, next semi-authorised, but then brutally disowned. Incredibly, in the run-up to the launch of John Le Carré: the Biography, Cornwell actually sold a rival “memoir”, The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories from My Life, to another publisher. Scarcely a vote of confidence, this was made worse by Cornwell’s contemptuous description of Sisman’s efforts as “thumbnail versions” of material he wished to “reclaim as [his] own”.

The Secret Life of John le Carré is less a revised and updated version, more an unfettered portrait of some confidential affairs on the grounds that these hold the key to Le Carré’s creativity. “My infidelities,” he claimed to Sisman, ”became almost a necessary drug for my writing.”

This reads like special pleading. And why should we believe him? His own website used to declare “Nothing that I write is authentic. It is the stuff of dreams, not reality. Artists have very little centre. They fake.” Worse, Cornwell’s assertion of infidelity as the key to his writer’s art is not vindicated by the truth of this “secret life”: a hollow catalogue of some heartless infidelities that’s less a guide to the springs of the novelist’s creativity than an awkward justification for five chapters about Le Carré’s love life. Not only do these affairs shed virtually no light on the novelist’s creativity, they are, in one crucial respect, old news. In 2022, Suleika Dawson scooped Sisman with The Secret Heart, a kiss ‘n’ tell potboiler that got a distinctly mixed press. This comes as no surprise. Cornwell’s “secret life” was, he admitted, a disaster; his affairs a weird mix of obsessive philandering and schoolboy romance. No one ever opened his novels for insights into the female heart. Still, for better or worse – and Sisman confesses misgivings – these episodes form the meat of this slim volume. But that’s not the end of the story.

Sisman is professionally too interested in the lives of others to suppress his part in the unfolding of this broken dream. His closing chapters bookend the disclosures of the “secret life” with more sad reflections on the aftermath of Le Carré: the Biography. Still unsure of his feelings, he is like a man who’s escaped a house on fire, relieved to be alive, but scorched and soot-blackened by the experience.

For instance, he admits he was conned as well as carbonised, never realising, he says, that the principal “party” in this project “whose sensitivities most required respect would be David himself”. He loved Le Carré’s company, but was “disappointed by what he had to say… stories with which I was already familiar”. Cornwell, meanwhile, continued to play cat-and-mouse, praising and flattering his biographer in one letter, then confessing “near suicidal” thoughts at what Sisman had written. Behind this mental cruelty, Sisman detected a pattern – in which “David would become very agitated” then “recover his composure” – but was unable to break the spell of Cornwell’s charm.

Where, in this maelstrom, is the measured exchange of private confidences between subject and author? The negotiations around Le Carré’s “secret life” compose a portrait of two literary men suffering a simultaneous nervous breakdown. One a manipulative carnivore, with an ice-cold heart; the other a disoriented herbivore accustomed to grazing on harmless, nutritious manuscripts, temperamentally unsuited to a visceral battle over territorial rights.

One golden rule of literary life has always been: Know Thy Genre. Biographers do best when they have no skin in the game. Here’s the bigger picture: Le Carré is dead; and his work lives on, for now. Who knows what the long-term damage these revelations will do to his reputation? My guess: not much. Cornwell has played his tricks; Sisman has had his say. Their project went off the rails for every possible reason, starting with the novelist’s immense vanity. Le Carré thought he could spin his exit to posterity as he’d spun his career. Sisman underestimated the writer’s fathomless guile. A more accurate title for this distressed, fascinating, and mildly vengeful, volume might be The Monstrous Charm of David Cornwell, a lament.

The Secret Life of John Le Carré by Adam Sisman (Profile Books, pp. 196, £14.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments