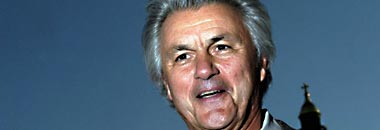

John Irving: The sting in the tale

John Irving's discoveries about the father who abandoned him have eerie resonances with the plot of his new book. The novelist talks to Robert Dawson Scott

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Irving's demotion of his own life as a subject of enquiry, however, is more telling than he would like you to know. It underlies a kind of reclusiveness that may not be in the JD Salinger league, but has nevertheless led to a strict rationing of his public and media appearances. You will find the odd online interview, the occasional, brief book-launch sound bite, but for a man whose books are sold by the million, they are rare. His visit to the Edinburgh Book Festival two years ago was the result of more than a year of patient lobbying by Catherine Lockerbie, the festival director and an Irving enthusiast. Significant TV appearances in the past 20 years are rarer still, even in America.

When he does talk, whether to journalists or to his many admirers, he has always steered the conversation away from his life story. He will talk happily about all sorts of apparently personal details - how he writes, for example, in longhand at first, then on a typewriter. Ah, that's what's missing in the otherwise ordered but comfortable room - a computer. "I don't even know how to turn one on," he growls. At least the typewriter is electric. "I work every day, I work seven days a week. I get up early - I like to be the first one in the family up - make coffee, put the dog out, that kind of thing. I'm probably at my desk writing between 7.30 and eight o'clock every morning."

He will talk happily about his literary tastes: he likes Dickens, Rushdie, Garcia Marquez, the Canadian Robertson Davies; he doesn't like Thomas Pynchon or anyone he sees as deliberately, or at best carelessly, obscure. "The plot is why I do it," he explains. "If I had read many modern or postmodern writers when I was a kid, I don't think I would have wanted to be a novelist." As it happens, he read Dickens, who remains his hero. Even the dog, a chocolate-brown Labrador, is called Dickens.

He will talk happily - not to say endlessly - about wrestling, at which he excelled as a youth and in which he has maintained a lifelong interest as coach and referee. Even now, he has a large gym in his house and spars regularly. (This is proper wrestling, by the way; the kind you get in the Olympics, not the preposterous posturing of the professional circuit.)

Irving is amused, but rather proud, that he was inducted to the national Wrestling Hall of Fame a decade before he was admitted to the hallowed halls of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. "Let's just say I suspect there was some opposition," he grins, knowing full well that there is still a rump of critics who distrust Irving's superficially old-fashioned, plot-driven books as just too enjoyable to be taken seriously, "and it took a while for my friends to bully my nomination through."

But one thing he never talked about was his father - at least, not until now. He has never made any secret of the fact that he was abandoned by his natural father when he was two. But he has declared, loudly and as often as he was asked, that he enjoyed a happy, carefree childhood with his mother and stepfather Colin Irving, whom he loved dearly and whose name he took. In particular, he has always insisted that all those fatherless boys and single mothers in his novels, from Homer Wells in The Cider House Rules to Jenny Fields in The World According to Garp, are wholly fictional creations and nothing to do with any events or feelings that may or may not have occurred to him.

If you are one of his many readers who have seen those recurring tropes and wonder if there might be rather more to it all than meets the eye, you're not alone. Janet Turnbull, the Canadian publisher who became his second wife in 1987, tried to talk to him about it during the course of their swift but charmingly romantic courtship. "I asked about his childhood - 'How is your life mirrored in your novels; did you know your father, and so on?'" She too was rebuffed. "He went straight into denial mode - 'I don't care, it doesn't matter to me, I had a happy childhood...' I remember thinking, 'This is a man who might be in denial about what he really felt about not knowing his father.'"

Now, at the age of 63, Irving has recanted, in the most complete and public manner imaginable. Not only has he given unprecedented access to a Scottish television crew for an hour-long documentary to be screened on BBC4. But in the course of an extraordinarily candid interview, he accepts that his life and work have, after all, been intertwined all along in the most personal and painful of ways.

First, he talks freely for the first time about his father, a man named John Wallace Blunt, now deceased. He admits now that the absence of his father, not so much as a physical presence but as a source of approval and validation, has driven most of his writing most of his life (not to mention his wrestling career before that). "My imaginary reader has been my father," he says. "Surely, in one novel after another, I've been inventing fathers. I've been making them up. I have a ceaseless capacity to make up the missing part, to fill in the blanks, and he was a blank in my life. I have largely created who he was because of the absence."

That is just the beginning. Four years ago, just as Irving was in the middle of writing his new novel (one which has the search for a missing father as the central plot line), a man called Chris Blunt contacted the Iowa Writers' Workshop, where Irving had studied with Kurt Vonnegut in the 1960s. Chris was his half-brother - and there were three other half-siblings. Irving confesses that, for once, his imagination had failed him; he'd never thought that his father might have had other children. "But he was only 22 when he had me. Of course he would know other women, he was married four more times and had children with three of his wives."

When the two men finally met, Irving recalls: "We hardly talked. We just looked at each other, because I'm looking at someone who looked so like one of my children, and he's looking at someone who resembled our father in his later years. We just stared. It was very strange."

As if all that were not enough, Irving turns to another revelation from his childhood: his early sexual initiation, at the age of 11, by an older woman. It left him with an interest in older women well into his thirties, which he now considers was inappropriate but which at the time felt, well, pretty good. "I never felt abused or molested," he says. "That's an adult concept. I was young enough not to know that I was having sex. It wasn't until I was old enough to be having sex on my own initiative that I realised, 'Oh, this isn't the first time. This is something that has happened to me before.'"

Part of the long-term effect was a kind of false expectation of his sexual partners. As he points out, and as anyone who can recall their first adolescent fumblings will acknowledge, if you start off with someone who knows what they are doing, it will be better than with a fellow fumbler.

But why is Irving suddenly going public with all this? Cynics will no doubt point to the imminent release of Until I Find You, his 11th novel and, at more than 800 pages, his longest to date. It features an actor, Jack Burns, who loses his father when he is very young and, in the course of a typically Irving-like cavalcade of church organists, tattoo artists, choirgirls and the seamier side of many of the ports of northern Europe, spends most of his life searching for him. Among other experiences - wouldn't you know? - his hero has sex, aged 10, with an older woman.

So can we ascribe this sudden confessional to the need to hype a book? I don't think so. Sure, Irving has taken a conscious decision to talk publicly about this at this moment. It is not something a man in his position just blurts out to a passing TV crew by accident. But you only have to see the shadow pass across Irving's face when he talks about how he longed for the approval of his father, how he used to imagine that his father was part of the crowds at his college wrestling matches, to grasp that this is far more important to him than a few more books sold.

You only have to see, as well, the powerful wrestler's shoulders slump when he recalls the publication of The World According to Garp, his breakthrough work, nearly 30 years ago in 1978. What should have been a moment of triumph was instead a moment of despair.

"The first thing I thought of when that novel made me famous," he says, "was, 'Now he'll come find me. Now he'll identify himself.' I think I felt more disappointed in the aftermath of that publication than I did at any other time. The blow was - if he's not interested in me now, he must never have been."

Irving did not go in search of his father, perhaps because that would have meant having to admit that his childhood had not been so idyllic after all. But about three years later, just as he was divorcing his first wife, his mother reopened the wound by giving him a packet of letters written to her by his father during the Second World War, when Irving was still an infant. There was even a picture.

"Anyone could see we were related," Irving says, showing it alongside a picture of himself at much the same age. And indeed, the dark eyes, straight brow and steady gaze are remarkably similar. Among the information contained in the letters was that Blunt, a US Air Force pilot, had been in the Far East during the war, flying Liberators over what was called the Hump - the route from India to China over part of Japanese-occupied Burma.

This was a detail that Irving deliberately used in the character of Wally the aviator in The Cider House Rules. "It was an offering," he explains. "Plagiarising my father's letters to my mother and putting them into a novel was my way of saying, 'If you're out there, if you do read me, hello, I know something about you.' But I never heard from him. And that, to me, is probable evidence that he did not know I was John Irving, the writer, or at least that he did not read that book. If he had read that book, I don't think he could have resisted making contact."

There is one further twist in the tale. One of the pieces of information Chris Blunt gave when they met in 2001 was that their father had died in 1996. It would be tempting to conclude that that was what unblocked the dam and allowed Irving finally to let out the hurt he had held in for so long. But, in fact, Until I Find You had been in progress before that. Typically for Irving, the plot details had been worked out before he began the main writing.

In that plot, Jack Burns finally finds his long-lost father. Irving is happy to disclose the plot, reasoning that no book of that length, which left the father unfound or dead, would be very satisfactory to read. But the father is in a sanatorium, in effect insane. Chris Blunt had also told Irving that John Wallace Blunt had been severely bipolar and had finished his life in more or less the same state as the fictional one Irving had invented, an eerie collision between real life and the world of the imagination.

"It was disturbing to discover that my real father was crazy," he reflects. "Why would I have imagined my father was insane?" And then, half gleeful at his own cleverness, half tearful at what it portends, he produces his own answer. "That would be the only excuse I could imagine to explain why he didn't try to find me - because he was crazy."

To say the new book has been something of a watershed, then, is hugely to understate the case. As Janet Turnbull puts it, with touching pride: " There's been a turnaround here. He's saying he was wrong about something and he has changed his mind about it."

Somewhere in the creative process, too, something cracked. The new book was originally written in the first person, a technique Irving had used before - in A Prayer for Owen Meany, for example - but still a deliberate choice. After the book was finished and delivered to his publishers - the rumour is that it was the very next day - he took it back and rewrote all 800 pages from top to bottom in the third person, cutting about 25,000 words in the process.

To make such a fundamental structural change at such a late stage was something he had never done before, and it underlines how volatile the material was for him. "I felt it would be a relief to me to give myself some distance from Jack Burns," he says now, confident that it was the right thing to do. "I felt I wasn't writing about myself any more." Perhaps some things are better left to the imagination after all.

Robert Dawson Scott is the producer, for Lion Television Scotland, of 'John Irving: My Life in Fiction', to be broadcast on BBC4 at 9pm on 18 August. 'Until I Find You' is published by Bloomsbury (£18.99). John Irving appears at this years's Edinburgh International Book Festival

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments