How literary giant Jean Rhys became a jazz songwriter

On the 40th anniversary of the author’s death, Martin Chilton looks at her little-known collaboration with George Melly and The Feetwarmers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Forty years after her death, Jean Rhys is regarded as one of the great writers of the 20th century. Time magazine included Wide Sargasso Sea in its “100 best English-language novels since 1923” – but one side of her career that has been neglected is a musical one: Rhys penned a witty song about broken love for jazz singer George Melly.

In the late 1970s, when Rhys was in her late eighties, she lived with Melly and his wife Diana on the top floor of their home in Hampstead. She was a difficult house guest, drinking heavily and prone to bouts of depression. One moment she could be charming and funny, the next bitter and displaying an irascible temper.

Melly was then in the relatively early years of a 30-year musical partnership with my late father, John Chilton. The ebullient singer would update him with tales of their famous literary house guest – including the time she broke the lavatory cistern. “It’s like having Johnny Rotten in the house,” he joked.

Diana, who along with literary executor Francis Wyndham later co-edited the author’s correspondence, looked after Rhys with patience and kindness. “George Melly’s wife had Jean to stay in her house for a whole winter,” recalls writer and friend Diane Athill. “My God, that was a testing thing. Di was a saint. And Jean was terrible, because Jean was drinking a lot at that stage, and she really was a pain.”

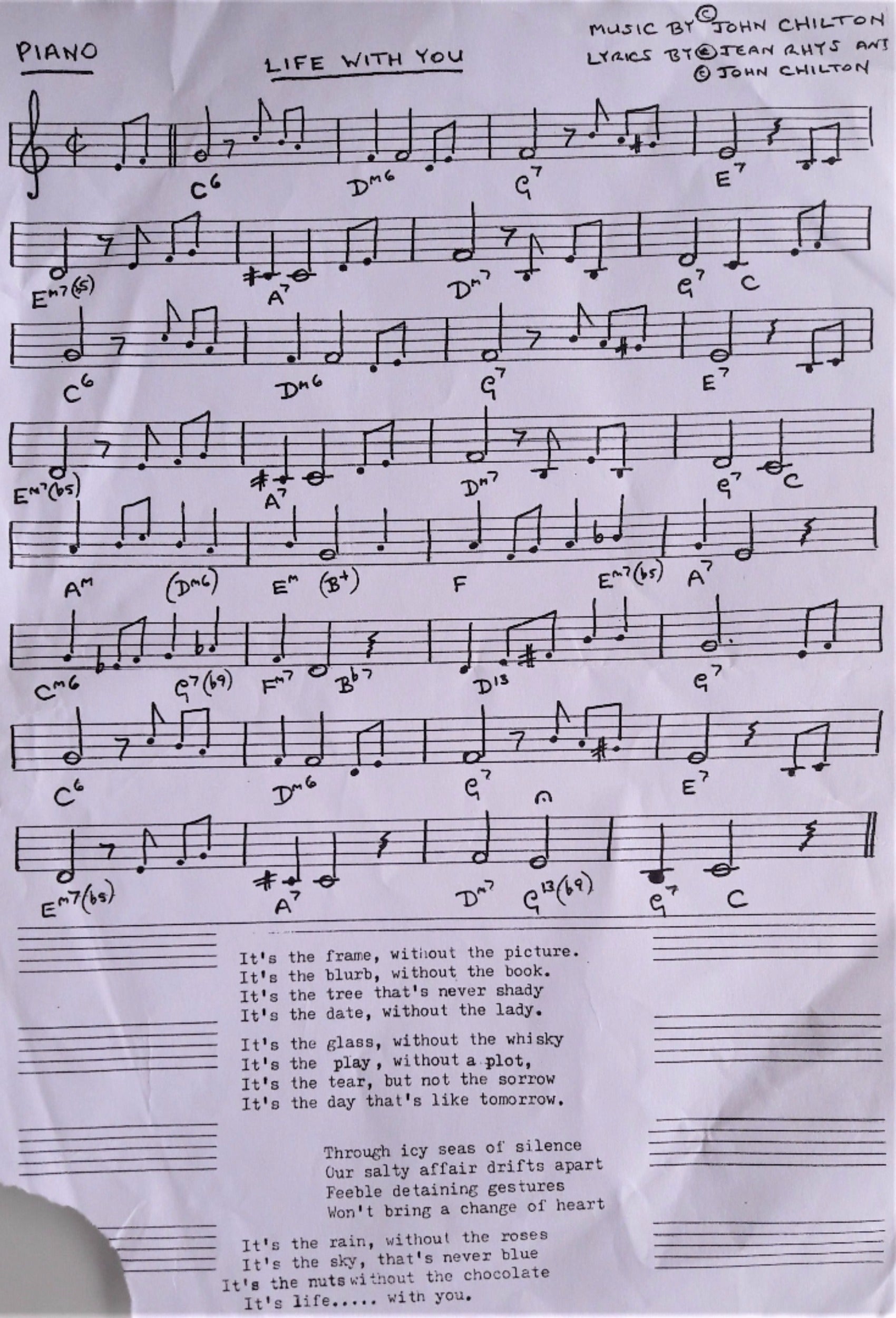

Melly, with trumpeter Chilton and his band The Feetwarmers, played an annual month-long Christmas season at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in London. Rhys enjoyed going regularly to see them in the smoky Soho club. One night, she handed my father a sheet called “Life With You”, containing what she described as “a small bittersweet poem about love”. She envisaged it as a song and asked if he could put a melody to the words.

Rhys was a fan of jazz. She loved the Great American Songbook classic “One for My Baby (and One More for the Road)” – by Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer – and would occasionally request that Melly and the band play her favourite Bessie Smith song, “Nobody Knows You When You Are Down and Out”. She was also an admirer of Billie Holiday and told my father, who had recently completed a biography of the singer called Billie’s Blues, that her favourite Holiday song was “Time on My Hands”. She liked hearing tales of Holiday’s drinking.

My father, a Grammy-winning jazz historian, would occasionally write songs when the mood took him. His composition “Give Her a Little Drop More” was sung by Rob Lowe, Demi Moore and fellow Brat Packers in the movie St Elmo’s Fire, for example. A few years after Rhys’s death on 14 May 1979, he was urged by Melly to look again at the wonderfully satirical lyrics the author had written.

Chilton discussed the song with Wyndham, who said he was excited by the idea. He set them to a melody for piano and devised bridging chorus lyrics for the middle section to hold her lines together. “I love your addition to Jean’s lyric,” Wyndham wrote in January 1988, as he approved Melly’s proposal to put the song on a new record. The novelist, who had been married three times and written about her deeply unhappy affair with Ford Madox Ford in the 1930s, found an acerbic way to describe a failing relationship:

“It’s the rain without the roses,

It’s the sky that’s never blue,

It’s the nuts without the chocolate,

It’s life… with you”.

Melly recorded the song with The Feetwarmers for their 1988 PRT album Anything Goes. The song was produced by Terry Brown – who had overseen hundreds of iconic records in the 1960s including Donovan’s “Mellow Yellow” and worked on numerous Rush albums in the 1970s. They tested the song out in live shows and the audiences always responded enthusiastically to Rhys’s bleak, funny anti-love song.

Rhys, who had been born Ella Gwendoline Rees Williams in 1890 on the island of Dominica, was residing with Melly and his wife because her bungalow in the Devonshire village of Cheriton Fitzpaine was too remote and cold for comfort during the winter months, when she wanted to write. The author, once praised by The New York Times Book Review for an “unblinking truthfulness” that made her “quite simply, the best living English novelist”, was looking back on a career of ups and downs. Her admirable back catalogue included The Left Bank and Other Stories (1927), After Leaving Mr Mackenzie (1930), Good Morning Midnight (1939) and Sleep It Off Lady (1976).

In January 1979, my late mother Teresa and my father went for lunch with Rhys and the Mellys at their Hampstead home. Nearly 30 years later, my mother, by this point in a care home in north London and approaching death, talked at length during one visit about her memories of meeting Rhys. She recalled that Rhys had a tiny, whispery voice – which would break out into an abrupt, rich laugh – and said that the author told her how pleased she was to hear that mum’s favourite of her novels was After Leaving Mr Mackenzie and not Wide Sargasso Sea.

Wide Sargasso Sea, Rhys’s feminist prequel to Jane Eyre, had restored her to public attention after decades of obscurity – winning the WH Smith Literary Award in 1967 – and it remains popular. It has been adapted for radio by the BBC, inspired a West End play by Polly Teale and has been made into a movie starring Karina Lombard as Antoinette Cosway (known as Bertha Mason in Jane Eyre) – the original mad woman in the attic and Mr Rochester’s first wife. Wide Sargasso Sea also inspired an eponymous song by Stevie Nicks. Linda Grant said she once “scandalised an audience at the British Library by claiming it was a greater novel than Charlotte Brontë’s”.

At the time of that lunch, Rhys had started on her life story, which was published posthumously as Smile Please: An Unfinished Autobiography. She talked to my mother about her experiences in London as a young girl and the discomforts of old age, including the problems of having a bad back. “The only care home that I could possibly bear would have to have a good bar and a generous barman,” she joked, a quote my mother was able to recite, and laugh about, as she considered her own grim situation at the time. Rhys did in fact move into a nursing home in Devon a month or so after that lunch (one, alas, without a bar) and died in hospital in Exeter shortly afterwards at the age of 88.

Not long before meeting my mother, the “reclusive” Rhys was interviewed by the New York Times and “refused to be photographed”. She told my mother that she had always had an aversion to having her picture taken. My mother had been a photojournalist in the 1950s, taking portraits of Louis Armstrong and Marlene Dietrich among others, and was delighted when Rhys agreed to pose for her. Her photographs are published in The Independent for the first time, and are certainly among the last ever taken of Jean Rhys.

The author’s legacy lives on and continues to inspire 21st-century readers and writers. Caryl Phillips’s well-received novel A View of the Empire at Sunset, published in 2018, is about Rhys’s life as a troubled young woman trying to make her way in England during the early years of the 20th century.

Troubled emotions were always at the heart of the work of Rhys, a novelist who said that when she wrote “the feelings are always mine”. “Life With You” is a jeu d’esprit of songwriting, which sparkles with Rhys’s characteristically lyrical descriptions of despondent love:

“The tree that’s never shady,

The date without the lady,

The tear but not the sorrow,

The day that’s like tomorrow”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments