Books of the month: From Isabel Allende’s ‘A Long Petal of the Sea’ to Alice Vincent’s plant-themed memoir ‘Rootbound: Rewilding a Life’

Martin Chilton reviews six of January’s releases for our monthly book column

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

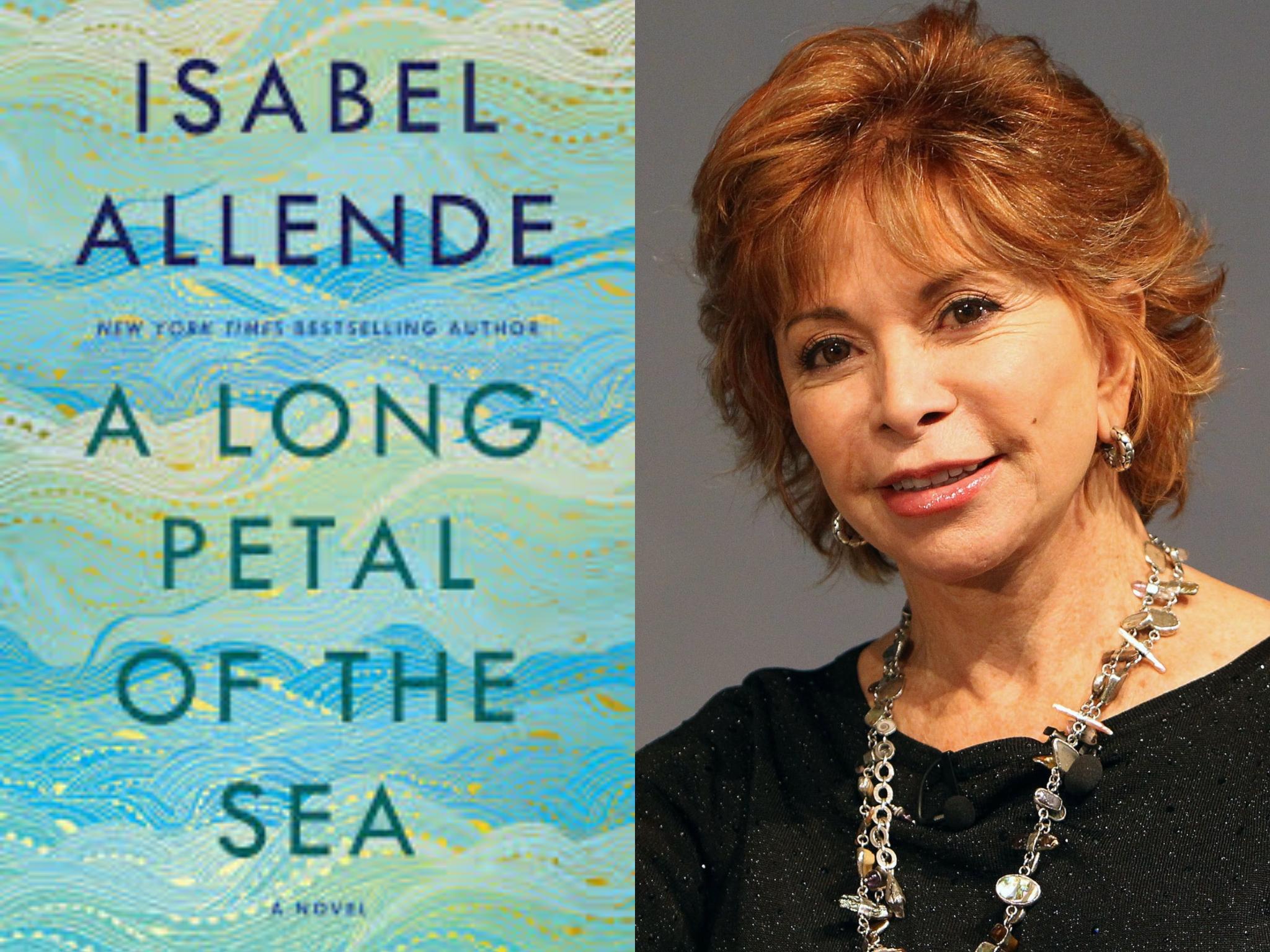

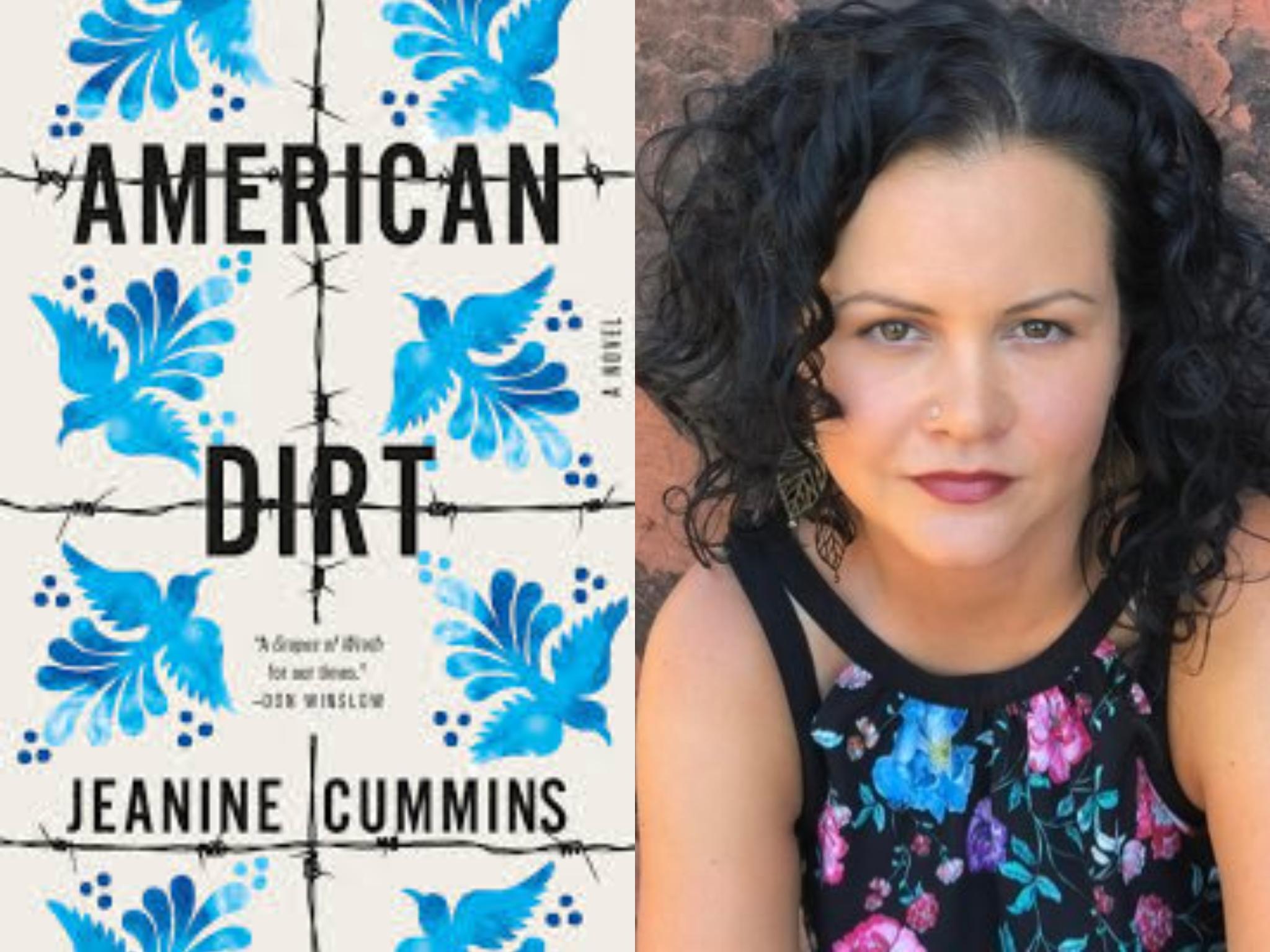

Your support makes all the difference.If January is anything to go by, 2020 will be a terrific year for books. Two outstanding new novels share a theme of holding on to love during desperate flight. Isabel Allende’s A Long Petal of the Sea and American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins are also linked by the work of Nobel Prize-winning poet Pablo Neruda. The late Chilean chartered the SS Winnipeg to bring migrants from fascist Europe to his homeland, a journey taken by the refugee doctor Victor in Allende’s haunting novel.

A quote from Neruda’s The Song of Despair (“there were grief and the ruins, and you were the miracle”) is used in the epigraph that opens American Dirt, a sensational story about the gruelling experience of illegally crossing the US-Mexico border. The stories by both women, although full of despair, are also life-affirming triumphs.

The Grim Reaper seems to be rampant in this month’s releases, whether fiction or non-fiction. Kim Young-Ha is one of South Korea’s masters of modern fiction and his hugely enjoyable collection of short stories, Diary of a Murderer (Atlantic Books, translated by Krys Lee), includes a title story about an ageing serial killer with memory loss. The murderer looks back on his “one-man war against the world” as he considers one final target: his daughter’s boyfriend.

Rachel Clarke’s Dear Life is a moving memoir by a doctor who specialises in palliative care. It is a magnificent, tender book. Finding ways of staving off the inevitable end for all of us is the message of Graham Lawton’s This Book Could Save Your Life: The Science of Living Longer Better (John Murray), in which the New Scientist journalist offers an evidence-based guide to living healthier.

One of the most anticipated books of early 2020 is Deborah Orr’s posthumous memoir Motherwell: A Girlhood (Weidenfeld & Nicolson). Orr, who died of cancer in October, recounts growing up in Scotland, under the close eye of her mother, in this sharp, candid life tale. Another excellent personal story is Alice Vincent’s Rootbound: Rewilding a Life, which mixes memoir and astute musings on how the millennial generation is finding solace in the power of plants.

London has always been a fertile ground for literature and Francesca Wade’s Square Hunting (Faber) is a marvellous history of the pioneering writers who lived in Mecklenburgh Square between the world wars. Wade offers a perceptive, well-researched account of five exceptional women – Dorothy Sayers, Jane Harrison, Eileen Power, Virginia Woolf and the poet known as HD – and how a historic square in Bloomsbury provided these writers with a haven of independence, allowing them to pursue trailblazing work.

Jane Austen, who wrote about nearby Brunswick Square in her novel Emma, also gets fresh attention this month. The Other Bennet Sister by Janice Hadlow (Mantle) is a novel that will delight Pride and Prejudice fans, as will Miss Austen by Gill Hornby (Century), which delves into why Cassandra Austen burnt the famous novelist’s letters, 23 years after her death.

Austen’s sister was clearly worried what would be made public if the letters saw the light of day. In Crisis of Conscience (Atlantic), Tom Mueller argues that we now at least live in “the age of whistleblowing”. Not everyone is happy with this development. President Donald Trump, who imposed “anti-leak training” on government departments, has reduced the chance of some healthcare investigations by reassigning most of the prosecutors of the Department of Justice’s Health Care Corporate Fraud Strike Force.

There are some important “serious” books this month. Kim Ghattas’ Black Wave: Saudi Arabia, Iran and the Rivalry That Unravelled the Middle East (Wildfire) is a compelling account of the entrenched rancour between two important countries in the Middle East. Emmy-winning journalist Ghattas details a depressing “race to the bottom” since 1979, but she also celebrates those courageously fighting for freedom in such a toxic era.

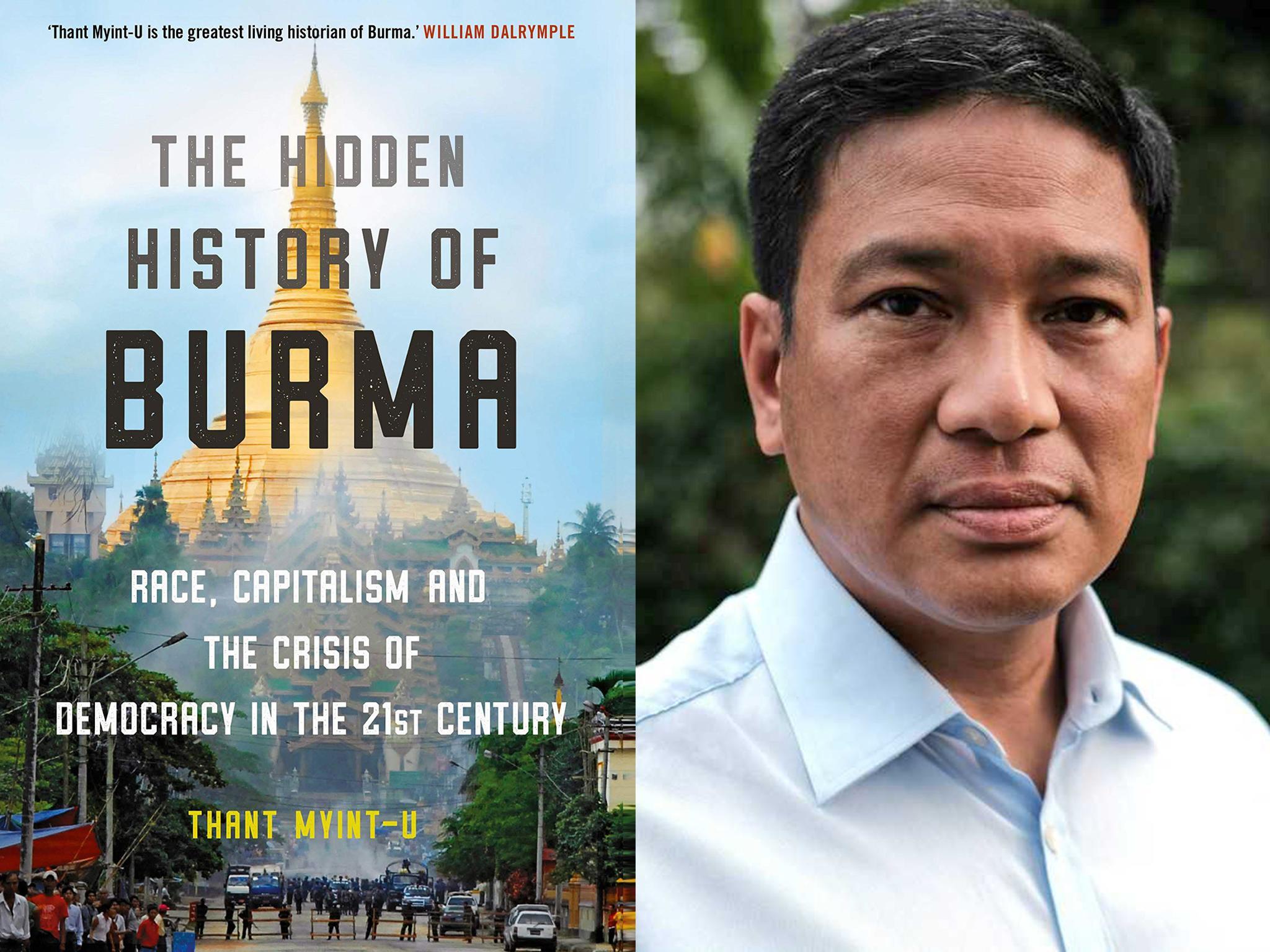

Allegations of genocide put Myanmar (still also known as Burma) back into the headlines at the end of 2019, and Thant Myint-U’s fascinating The Hidden History of Burma is a timely reminder of the importance of intelligent social history.

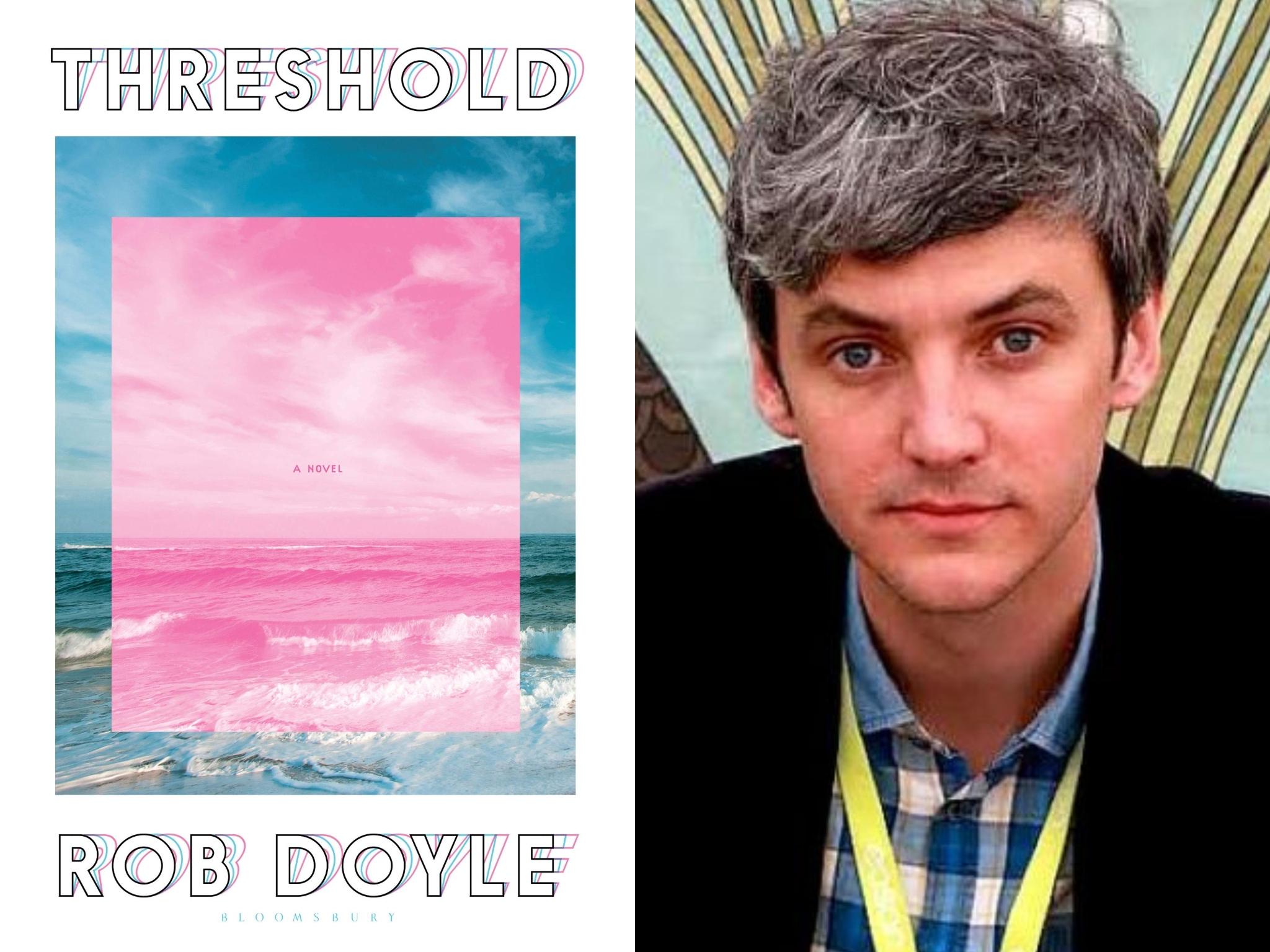

Among the best new thrillers this month are Peter May’s A Silent Death, Rory Clements’ Hitler’s Secret, Chris Hauty’s Deep State, Stephen Leather’s The Runner, Rosamund Lupton’s Three Hours, Liz Moore’s Long Bright River, Jo Spain’s Six Wicked Reasons, Francine Toon’s Pine and William Gibson’s Agency, a science fiction novel set in a post-apocalyptic London. Threshold, by Rob Doyle, is a wild, funny tale about drugs and the life of a ligger traveller. Drug-filled misadventures are also a feature of Jeet Thayil’s entertaining novel Low.

There are some highly impressive debut novels this month, especially Molly Aitken’s The Island Child (Canongate), about identity and motherhood, and Deepa Anappara’s Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line (Chatto & Windus), a tense story based around the disappearance of children in present-day India. A Good Man, by Ani Katz (William Heinemann), is a striking modern tale of violence, sexual abuse and vindictiveness. Katz’s edgy novel examines a dysfunctional family, a failed relationship and a modern culture in which a violent man can see more to worry about in “invading” phone privacy than in violating a woman’s body.

Perhaps the most outlandish tale this January is Eoin Colfer’s Highfire (Jo Fletcher Books), which is a funny, offbeat adult fantasy novel from the author of Artemis Fowl. Highfire is about the friendship between a hard-drinking dragon called Vern and a Louisiana bayou swamp kid. The dragon, who “risks his scaly ass” to rescue the boy from a mob-run hotel, does not have a high opinion of humans. Most of them, he quips, are “dumber than pig shit in a slop bucket”.

In the latest of our “books of the month” column, we review six books published in January 2020.

The Hidden History of Burma by Thant Myint-U ★★★★☆

Some of the problems of Burma (Myanmar) go back to colonialism. George Orwell, who was a policeman there in the mid-1920s, said, “if we are honest, it is true that the British are robbing and pilfering Burma quite shamelessly”. It was drunken British soldiers who burnt the irreplaceable royal library to the ground in 1905. Burma, embroiled recently in allegations of genocide, is now on Fodor Guides’ list of the top 10 places in the world to avoid.

Thant Myint-U, who worked with the United Nations for more than a decade and is considered the greatest living historian of his country, explains in the introduction why he uses Burma instead of Myanmar throughout this compelling, bleakly fascinating book on the country that is precariously positioned between China and India.

Burma has suffered from brutal military rule, and many of its people live in disease-ridden slums. The country has been hit by droughts; epic floods have displaced millions of its people. Things are only going to get worse: Burma is set to be one of the five countries in the world most negatively impacted by climate change. Despite its rich natural glories – it has the largest populations of wild elephants in Asia – there is a huge problem with wildlife trafficking to China.

Myint-U offers a humane analysis as he reflects on national identity and the dangers of nationalism, and his conclusions are not cheery. Burmese people are consistently left at the bottom of the heap, says Myint-U. Their lives are a tale of “disappearing forests, polluted rivers, contaminated food, rising debt, land confiscation, and most recently cheap smartphones, internet access and Facebook pages on which they see for themselves, and for endless hours a day, the lives they will never have”.

The Hidden History of Burma: Race, Capitalism, and the Crisis of Democracy in the 21st Century by Thant Myint-U is published by Atlantic Books on 16 January, £18.99

A Long Petal of the Sea by Isabel Allende ★★★★★

Isabel Allende, who won the 2014 Presidential Medal of Freedom, is an accomplished storyteller and her new novel A Long Petal of the Sea is an epic that starts in 1939 and spans decades and continents.

The main characters are Roser, a pregnant young widow, and Victor, an army doctor and the brother of Roser’s dead lover. They have to flee General Franco’s Spain, a treacherous escape that culminates in joining 2,000 other refugees on the SS Winnipeg, heading to Chile. The ship was chartered by the poet Pablo Neruda, and one of his quotes (“the long petal of sea and wine and snow”) provides the title of the novel. In order to survive, the two are forced to get married. This subtle emotional story is also an exploration of the fate of refugees, who faced a “campaign of fear and hatred”. Their rollercoaster lives involve concentration camps, persecution, violence and military coups.

Victor comes to understand that the most important events in his life are almost completely beyond his control. After watching the tragic death of an adolescent, Victor fears that his heart has finally broken. “It was at that moment he understood the profound meaning of that common phrase: he thought he heard the sound of glass breaking and felt the essence of his being was poured out until he was empty,” writes Allende.

Her novel is based on real events and individuals. The Peru-born novelist, herself once a political refugee, explores the nature of a person’s roots and why a sense of place is so important. A Long Petal of the Sea is a masterful work of historical fiction about hope, exile and belonging and one that sheds light on the way we live now.

A Long Petal of the Sea by Isabel Allende is published by Bloomsbury on 21 January, £16.99

Threshold by Rob Doyle ★★★★☆

The narrator of Rob Doyle’s Threshold is on a wild, sleazy, drug-filled odyssey that takes him around the globe. In a Berlin nightclub he encounters a man crawling on his hands and knees “across the slosh of piss and filth”. When he tells a friend that he’s just had an insane encounter with a man who wanted to drink his piss, he is met with a deadpan reply: “Oh yeah, the toilet guy”.

Doyle’s novel is a humorous delight – and more thoughtful than the previous scene might suggest. Dublin-born Doyle is a former philosophy student and his novel delves into the mind of a young writer (and slacker) who is travelling the world, thinking about Buddhism, modern society, meditation and drugs. Lots of drugs. You learn a great deal about magic mushrooms, hallucinogenic plants, ketamine and DMT (N,N-Dimethyltryptamine) as you experience his tumultuous pilgrimage.

The protagonist leaves behind Ireland (“a backwater of banal, misshapen people”) and his part-time job writing newspaper ‘think-pieces’ (“opinions are the sewage of the world, aren’t they?”) to travel around Asia and Europe. He has sufficient self-deprecation to reflect on a scrapheap of flops that includes his failure to write “the great backpacker dropout novel” or “the great Berlin techno novel”.

The narrator’s past love life runs through the novel like a dripping wound. War images recur. He looks back on his youth as “a campaign of revenge against women” and says his failed relationships have piled up, “like burned-out tanks on the battlefield of my life”. Threshold has interesting things to say about flawed masculinity and sexual obsession.

The novel has a sprawling jazz feel – bebop musicians Thelonious Monk and Miles Davis are namechecked – and seems to deliberately provoke as well as sooth. “The self throbs like a toothache,” says a narrator who is increasingly worried about the diminishment of his looks and powers – “my own reckoning with the ancient headf*** of ageing”, as he puts it.

In one moment of musing, culture itself is described as “a consolation prize”. That may be true, but Doyle’s maverick novel deserves the accolades coming its way.

Threshold by Rob Doyle is published by Bloomsbury on 23 January, £14.99

American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins ★★★★★

Hundreds of migrants die every year attempting the terrifying ordeal of crossing the US-Mexico border. Most die from heat stroke, dehydration or hyperthermia. For Lydia Quixano Perez, a bookstore owner, and her eight-year-old son Luca, the need to flee her Acapulco home and reach American dirt is propelled by deadly necessity. She has to flee a drug cartel boss, who has just brutally murdered her investigative journalist husband, her mother and 14 other friends and relatives.

Right from the shocking slayings that open the novel, Jeanine Cummins captures the horror of modern-day Mexico – a place where murder is shockingly casual in “a gang pageant of blood and grisly one-upmanship”. The chase-escape narrative is told in gripping, cinematic style, and it is easy to see why Hollywood leapt to option American Dirt. The expertly paced depiction of people forced to ride on top of the perilous freight trains known as la bestia, so they can travel out of sight to reach the border, is full of suspense.

As well as its exciting twists, American Dirt is full of deft touches and is so much more than a simple thriller. Cummins’ novel is an exploration of why humans are forced to leave their homes and migrate in the 21st century. It is a heart-wrenching, thoughtful story, which is so much stronger for concentrating on the victims of brutality and inhumanity rather than the perpetrators.

The main characters are memorable. Lydia (Mami) and her sparky, funny son Luca make a brilliant pair and Cummins has written an intensely affecting depiction of a mother’s love for her child. The remarkable sisters Soledad and Rebeca, who have to endure rape and torture as they escape from Honduras through Mexico, overcome their traumas with extraordinary resilience. Solidarity is an uplifting part of a grim plotline. Political points are made subtly and with humour, as when the American vigilante groups on the border are described as “playing night-time Power Rangers”.

Sexual depravity, greed and cartel violence are constant threats to the poor migrants, but American Dirt also contains unexpected acts of kindness. The reader joins Lydia in being nourished by these moments of common humanity.

American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins is published on 20 January by Tinder Press, £14.99

Dear Life: A Doctor’s Story of Love and Loss by Rachel Clarke ★★★★★

I was pretty sure I was in good hands after the first few pages of Rachel Clarke’s Dear Life: A Doctor’s Story of Love and Loss. Not only does she quote a Raymond Carver poem in the prologue, she also makes a droll reference to the “feral sidekick” in the Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan films, “a filthy-cheeked child known only as ‘Boy’.”

After working as a television documentary maker, Clarke retrained as a doctor in 2009 and now specialises in palliative medicine, working with patients who are dying from remorseless, vicious, incurable diseases. You understand why she says that “ageing is a privilege”.

She is shrewd and witty about the medical profession – there is a cutting anecdote about a flashy gynaecologist that the nurses secretly call ‘Goldfinger’ – and Clarke is candid about her formative experiences, particularly her own close encounter with cancer. The stories about her work with dying patients are memorable and profound.

As a struggling young doctor she confesses that she wished her own father, a wise and wily GP, was there “to guide me”. She also gives an eloquent account of seeing her father in decline, suffering from incurable cancer. It’s hard not to feel her pain as each new scan, blood test and bout of chemotherapy “bludgeoned a little more out of him”. Anyone who has cared for dying parent will be especially moved by the beautiful description of the moment she and her mother give their dying loved one a final shower.

The book should also be essential reading for anyone who cares about our beleaguered health system. Clarke powerfully conveys the battering the NHS has endured over the past decade of austerity, neglect that has resulted in overcrowded hospitals and the rise of “Corridor Medicine”.

In his poem, Carver says that “a sweetness” in life prevails at intervals given a chance. Dear Life is a painful read at times, because it forces you to reflect on some of the worst situations anybody ever has to face. However, the book is also a compassionate gem, full of its own episodes of sweetness. I won’t spoil the story, but Clarke’s true anecdote about the “magic string” that helps children facing radiotherapy is heartbreaking and inspiring.

Dear Life: A Doctor’s Story of Love and Loss by Rachel Clarke is published by Little Brown on 30 January, £16.99

Rootbound: Rewilding a Life by Alice Vincent ★★★★☆

Alice Vincent’s Rootbound, a book that blends memoir, history and horticulture, takes the reader on a year-long journey – with a chapter for each month – that ranges from the hidden parks of London, the wonders of Glastonbury, wildlife in Paris, Amsterdam’s botanic gardens, Berlin’s tree-lined streets and the “transportative” temple gardens in Japan.

But the book is also about a journey within, as Vincent, a champion of urban gardening who runs the popular Instagram account Noughticulture, tells the intimate and achingly honest story of her own quest to rebuild and re-root her life after sudden heartbreak, at a time when she felt like her life “had fallen off a precipice”.

Vincent articulates the experiences of the screen-addicted twentysomething generation who have discovered the restorative benefits of plants and gardening. Vincent says the “rhythms of nature gradually became a siren call” as she battled to clear the “chaos in my head”. Her description of the power of plants is stirring and earthily vivid, and the book shoots off at wonderful tangents. We learn about her family history of gardening, including her grandpa’s joy at his vegetable patch, and are shown the Victorian craze for ferns and learn about the 21st-century rise of “greenhouse popularity”.

Rootbound is also a tale of waking up to womanhood, whether from the supportive friendships in Vincent’s own life, or in the inspiring tales of female plant experts from long ago. It’s fun to read about the formidable Victorian botanist Marianne North (“I am a very wild bird and I like liberty”) who defied the conventions of her age. Gardens also hold secrets. Who knew that the sight of overgrown and bedraggled pampas grass outside a house was a clue that suburban swingers lived inside?

As the book explores the events of a troubled year, the sense of renewal is palpable, like watching a damaged plant struggle back to life. Vincent vividly conveys how the balm and calm of gardening helped her slowly climb out of the depths of despair and find a new way to ground herself. The book is also a love story. Intertwined with a hymn to nature is the story of how she fell for Matt, and how their feelings for each other gradually unfurled, as she dared to open her heart again.

Rootbound is a poignant testimony to the joy that greenery will bring to your life, and it is a magical reminder that humans, like plants, can mend and grow in their own good time.

Rootbound: Rewilding a Life by Alice Vincent is published by Canongate on 30 January, £14.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments