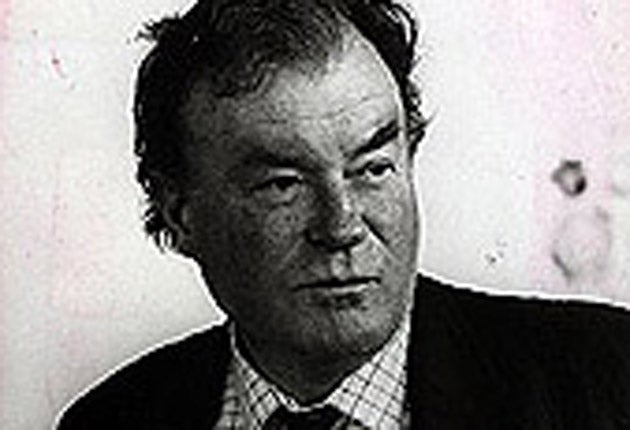

Invisible Ink: No 75 - Simon Raven

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Simon Raven was a cad. He had a passion for privilege, no sense of obligation, a fondness for beans on toast, and too much guilt about tipping waiters to be regarded as a gentleman.

Nor was he upper class – his family had made their fortune from socks. Born in 1927, he set out to live a hedonistic life, and in 1945 was expelled from Charterhouse for homosexual activities. Intelligent and charming, he had a tendency to strike 18th-century attitudes, marrying "for duty" and sending the notorious telegram to his penniless wife: "Sorry no money, suggest eat baby".

Despite only just avoiding a court martial for conduct unbecoming, he enjoyed his Army years and followed its instruction to be "brief, neat and plain" in his writing. He was employed by the publisher Anthony Blond on the condition that he left London at once, as it was getting him into debt, and set about producing chronicles of upper class life including The Feathers of Death and the eerie Doctors Wear Scarlet, which is now regarded as a classic.

A pair of novel cycles, Alms For Oblivion and The First-Born of Egypt, eventually ran (somewhat loosely) to 17 volumes. They take on a mystical edge, and supernatural occurrences always held a fascination for Raven. He said of his writing, "I arrange words into pleasing patterns to make money", and although he never found a huge readership, he did grow more industrious.

The public became familiar with his TV adaptations of The Pallisers and Edward and Mrs Simpson, and he also wrote dialogue for the Bond film On Her Majesty's Secret Service. His memoir, Shadows in the Grass was described as "the filthiest cricket book ever written", and Prion Humour Classics recently published a selection of his non-fiction writings, which include a treatise on recognising rent boys.

A gambler, flâneur, cricketer, controversialist, imbiber and fine host, he revelled in pushing his restaurant bills to astonishing levels. Of gambling, he cheerfully described "the almost sexual satisfaction which comes from an evening of steady and disastrous losses". Passionate yet aloof, dissipated yet energetic, Raven represents the perfect paradox of a certain type of Englishness. After obeying his publisher's restraining order for 34 years, he returned to London and died in an almshouse for the impoverished, regretting nothing. He wrote his own epitaph: "He shared his bottle, and when still young and appetising, his bed." Beware the man who boasts he was a friend.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments