The Indy Book Club: Michelle Alexander’s ‘The New Jim Crow’ reveals there is no justice in penal justice

When you say you think we should defund the police or abolish prisons, people look at you like you’re a conspiracy theorist. Reading The New Jim Crow gives you the tools to explain why these are entirely logical positions to hold, says Annie Lord

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.After he was convicted of a felony, Jarvious Cotton was not allowed to vote. Neither was his father, who was barred from voting after failing a literary test at the polling station. Or his grandfather, who was intimated into not voting by the Ku Klux Klan. Or his great-grandfather, who was beaten to death by the Klan for attempting to vote. Or his great-great-grandfather, who was a slave.

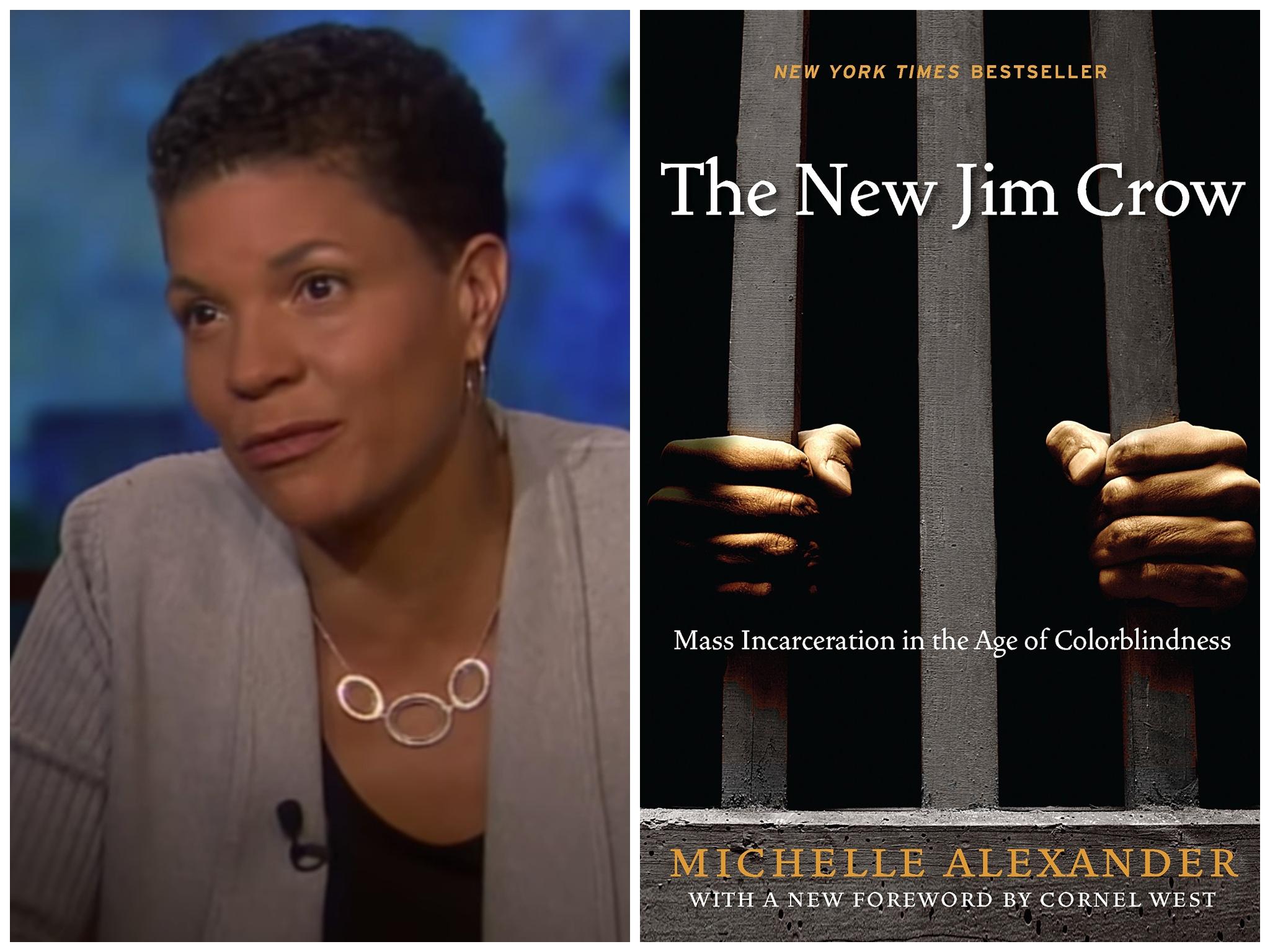

Lawyer and civil rights activist Michelle Alexander tells the story of Jarvious Cotton’s family tree at the beginning of her immensely clear-eyed, stark indictment of penal society, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. Cotton’s story shows how criminal “justice” is used as a system of control which targets and then denies people – particularly young black and Hispanic men – their basic human rights. Since the beginning of the war on drugs, those convicted for the possession and sale of illegal drugs, mainly marijuana, face extremely harsh sentences that leave them either languishing in jail or in and out of parole hearings for the rest of their lives. Once convicted, not only are they barred from voting, but they also face employment discrimination, housing discrimination, denial of educational opportunity, food stamps and other public services. First there was slavery, then there was Jim Crow’s enforced racial segregation and now there is mass incarceration. As Alexander affirms: “We have not ended racial caste in America; we have merely redesigned it.”

Since the beginning of the war on drugs, the US prison population has exploded from 300,000 to more than 2 million – and most of those new felons are black. In fact, today, the US imprisons a larger percentage of its black population than South Africa did during the height of the apartheid. In Washington DC, it is estimated that three out of four young black men can expect to serve time in prison. In the UK, the situation is similarly dystopic: black people in England and Wales are 40 times more likely than white people to be stopped and searched. Meanwhile, studies in both countries show that white people use and sell illegal drugs at remarkably similar rates to those of other races.

Starting right back in the early colonial period, at a time when race didn’t even exist as a concept, Alexander charts the mechanisms of power which that have entrenched racism so deeply in our society that we can no longer see how it functions. Alexander pays particular focus to the years after the civil war, when southern legislators designed Jim Crow laws to thwart the newly emancipated black population. Vagrancy laws made not working, “mischief” and “insulting gestures” into crimes that were then vigorously applied to black people. The aggressive enforcement of these criminal offences opened up an enormous market for convict leasing, in which prisoners were contracted to the highest private bidder to work on lumber camps, brickyards, railroads, farms, plantations, essentially building America for free. Alexander quotes W E B Du Bois’ assessment of this period: “The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again towards slavery.”

Alexander’s next focus is the “war on drugs” started by Ronald Reagan in 1982, which appealed to the public outcry for “law and order” – a racially coded backlash to the gains of the civil rights movement. In four years, Reagan oversaw the expansion of FBI anti-drug funding from $8m to over $95m. Meanwhile, money for drug treatment, prevention and education was dramatically reduced. The punitive treatment for drug offences was expanded further by President Clinton’s “three strikes and you’re out” legislation, which gave mandatory life sentences for a conviction of a violent third felony. While the law is “colour blind” in terms of who faces what punishment, those enforcing it are not, with police disproportionately targeting black neighbourhoods and convicting black people.

The current situation is dire. First-time drug offenders can face 10 years in prison. Thousands of innocent black people take plea bargains in order to avoid excessive mandatory sentences. On release, they enter “a closed circuit of marginality” in which opportunities remain closed off to them. None of this has led to a reduction in crime. But as Alexander explains, using a quote from the criminologist Michael Tonry: “Governments decide how much punishment they want, and these decisions are in no way related to crime rates.”

People like to imagine the racial caste system is dead and buried. Alexander explains how arguments to the contrary are met with disbelief. “Just look at Barack Obama! Just look at Oprah Winfrey!” She argues that the system depends on black exceptionalism to excuse itself. “The existence of black police chiefs [should] be no more encouraging today,” she explains, “than the presence of black slave drivers … hundreds of years ago.”

When you suggest that we should defund the police or abolish prisons, people look at you like you’re a conspiracy theorist. Reading The New Jim Crow gives you the tools to explain why these are entirely logical positions to hold. Books don’t save the world, but striking, unions, mass protests do. Yesterday, I saw a video of a Black Lives Matter demonstration in Florida where police let a black woman they had just arrested out of their car after a crowd gathered around it chanting “we protect ourselves”. It feels as though our attitude to punitive society is shifting. In the wake of George Floyd’s death, even Natalie Portman has pledged her support for defunding the police, telling her Instagram followers that “reforms have not worked”, calling instead for “reducing police budgets (& power) on a local and state level and investing that money directly into poor communities of colour through public services”.

The late Mark Fisher’s oft-quoted assertion that “it is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism” applies just as well when you change the word capitalism to prisons. But as people’s handcuffs are removed and policemen give up their badges, it feels like we might be starting to imagine a new future.

Here’s what some of our readers thought...

Matthew, 35, Lancaster

The way Alexander sets out her claims is perfect. Her writing is easy to read and isn’t clouded by footnotes, but is also really well researched. Other books on this topic I have found confusing but I could read this. No one should be barred by over-intellectualism from learning about something that is such an important issue: the way the criminal justice system keeps black people from fulfilling their potential.

Fedora, 28, Kent

I’ve worked in the violence prevention sector for 12 years now, and so I have understood the realities of the prison industrial complex for quite some time. As someone who focuses on systems of oppression, I tend to self-righteously roll my eyes when white people are “shocked” at blatant cases of discrimination or violence in their community. But reading this book, I was shocked by how far down the rabbit hole mass incarceration goes. The way Alexander traces the lines of history with clarity and well-backed up claims makes you question much of what you took as fact.

John, 26, London

I often avoid reading books that I know will make me angry. Not consciously but I just don’t pick them up as I know that doing so means fights at the dinner table, fights at work. I did pick this up and now I want to tear the entire system of government down and start again. It’s not nice knowing how far we are from a fair world, but it does make me return to the streets with Black Lives Matter with renewed vigour.

Our next Indy Book Club pick will be voted for by you. Send your thoughts to annie.lord@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments