So you want to be a novelist? A New York literary agent, editor and author reveal how bestsellers are born

For budding authors in the US and in the UK, the road to publication most often begins with a search for a literary agent. Clémence Michallon speaks to publishing industry insiders about the rest of the journey

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Stephen Barbara’s office is nothing to be afraid of. It’s a small, cosy space in Midtown Manhattan with a bookshelf in the corner and inspirational messages on the walls (“There is nothing new in art except talent” and “A mind needs books as a sword needs a whetstone if it is to keep its edge”). Barbara himself is a welcoming person. Though he does claim to be “very argumentative”, that side of his personality doesn’t manifest itself during our hour-long chat. He’s polite, voluble, and answers questions with the patience and precision of someone who loves the topic at hand. Yet most strangers who attempt to contact Barbara will agonise over their emails for weeks. They will ask their friends to proof-read their messages. They will hold their breath as they hit send. They will spend the next hours, days or weeks anxiously refreshing their email inbox. In other words, they will manage their communications with a level of anguish that seems irreconcilable with the perfectly pleasant person sitting in front of me. Stephen Barbara, you see, is a New York literary agent.

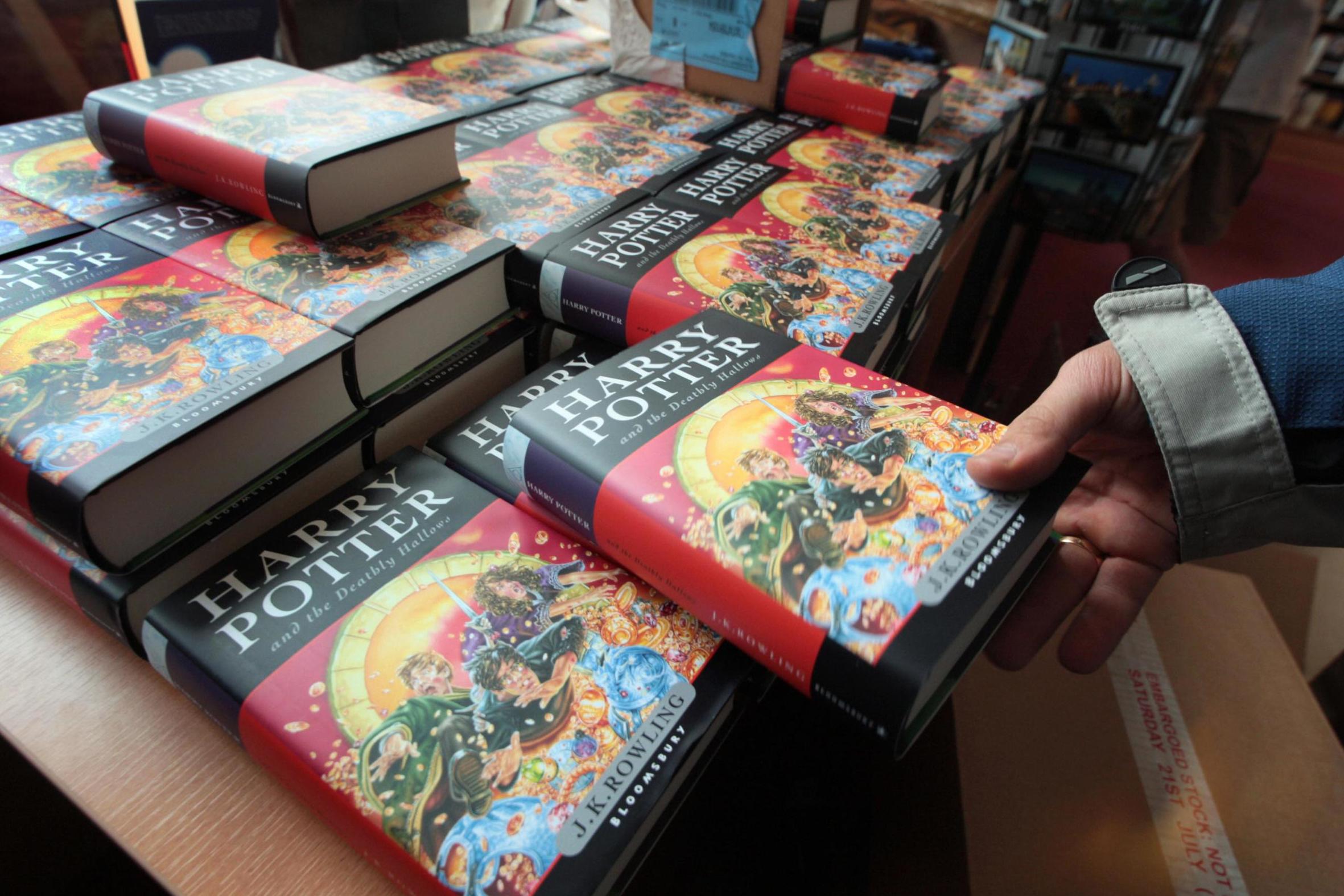

It’s easy to understand why people might tiptoe around someone like Barbara. Literary agents are, more often than not, the first point of contact for a writer looking to send their manuscript out into the world. Practices vary from one country to the next, but in the US and in the UK, most novels sitting on your bookshelves and on your nightstand likely began during a dialogue between their author and a literary agent. In other words, people like Barbara can jump-start careers in one of today’s most crowded professional fields – so a little tiptoeing might be in order.

Having been in his line of work for 12 years, Barbara, who now works at the InkWell Management literary agency, has built up an impressive roster of clients, including New York Times bestselling author Lauren Oliver (whose young adult novel Panic is being turned into a series for Amazon) and children’s author and National Book Award nominee Lisa Graff. And he has represented books by actor Krysten Ritter as well as Dylan Farrow (the daughter of Woody Allen and Mia Farrow, whose debut novel, Hush, is scheduled for release in 2020). Barbara, born and raised in New Haven, Connecticut, was originally destined to get a “very respectable job”, as a lawyer, perhaps – until his love of literature pulled him in another direction.

“I remember a lot of the books that I saw in my parents’ house, like The Firm and The Godfather or The Da Vinci Code and, um, Jurassic Park,” Barbara says. “I still dream of those books, you know, that sort of big, popular commercial book. And it’s something that I hope we could bring back a little bit.”

It’s not often that someone will comfortably cite The Da Vinci Code in a conversation about literature, but Barbara’s confidence reflects an important truth about literary agents: they literally cannot afford to be snobs. As a profession, they’re on the business side of things. Their job is to find books they can sell. And no, this isn’t nearly as cynical as it sounds: virtually all agents will only take on manuscripts they absolutely love, because loving a novel is a prerequisite for being able to sell it. It is entirely possible, however, for an agent to love a manuscript while thinking it will be a tough sell.

“Sometimes I might have a manuscript I like, but for some reason – there’s a big book that covers the same ground, or maybe the author’s last book didn’t perform as everyone had hoped – the timing isn’t great,” says Barbara. “Then it might be a conversation about waiting for just the right moment to submit it, or finding a slightly new angle to distinguish it.”

So how do manuscripts find their way into Barbara’s life – and how do they (maybe) become bestsellers? Broadly speaking, new projects land on his desk in one of two ways: either through a referral (for example, by an author he already represents) or through the “slush pile” – a not particularly flattering term used in the industry to refer to unsolicited manuscripts. That is how Barbara found his client Paul Tremblay, the author of the popular horror novel A Head Full of Ghosts.

“I think there’s a tension for agents where sometimes it’s very tempting to ignore the slush pile or roll your eyes at the slush pile,” he says – acknowledging that “strange” things, such as queries written in crayon, sometimes land in his mail. “But I think most people in publishing – we’re all dying to read something great. It would be so exciting to find something amazing. So you might go through hundreds of queries and hopefully something sticks out for you.”

Barbara does usually have an assistant who helps monitor the agency’s submissions folder, though on the day of our interview, her job was vacant, as she had just moved on to another company to be an agent herself. While there is an urban legend that claims agents don’t read their “slush”, Barbara expresses the opposite concern: ignoring unsolicited submissions could mean missing out on a hidden gem. And yes, new authors will sometimes get multiple offers of representation (queries are typically sent out in batches, so several agents will end up reading the same manuscript at the same time) – meaning agents must bear their competition in mind.

Budding authors are usually extremely curious about the slush pile, because it’s where their work is most likely to end up. So let’s stop and think about unsolicited submission and their place in an agent’s life for a bit. For Barbara, his reading system is “a pyramid of sorts”. “The things I have to read first are new manuscripts from my existing clients,” he says. “Then come works that arrive highly recommended from clients. We call those referrals, and they’re a great way to find new business. For “slush” – unsolicited manuscripts – we have interns and assistants who comb through those submissions and they might identify certain projects as having promise.”

Yes, having an established list of clients means it’s “a little harder to find time” for unsolicited queries – but it does happen, Barbara insists. “There are often clues in a query letter that someone is well worth paying attention to, so I do try to keep up with queries,” he says. “Most unsolicited submissions are not for me – it couldn’t be otherwise, statistically, of course – and I can tell in a few paragraphs. Over time you get a feel for it, you just know your own taste better and better.”

So what will prompt Barbara to go to bat for a specific project? Well, good, confident writing – the kind that makes you feel the author is comfortable running the show – is a start. High-concept, ambitious stories make him tick, as long as the writer can pull them off. A new voice – something that feels like it simply hasn’t been done before – is a good way to grab his attention.

Some clients might find another way into an agent’s path. Barbara came to work with Dylan Farrow and Krysten Ritter through the media and content company Glasstown Entertainment, which is itself a client. It’s not uncommon for people who have become famous through another line of work to turn to the publishing industry – mainly because they have a pre-existing audience, also known as a platform.

From an author’s standpoint, an agent can provide some much-needed guidance and support. “Working with an agent feels like constant affirmation that what you are pursuing is not only worthwhile, but even possible,” says Corinne Sullivan, a client of Barbara’s who published her debut novel, Indecent, in 2018. “Any writer will tell you that doubt is as much a part of the process as the actual writing, so having someone on your team who believes in your ability (and who is not your parent or significant other) can sometimes feel like the only reason to keep creating against all odds.”

With all this in mind, let’s say Barbara comes upon a brilliant manuscript, either through a referral or through an unsolicited query, and decides to take on the author as a client. What happens next? Well, he and the author will take some time to polish the manuscript together. Then, his mission – as he stresses several times – is to get the right person to read it as promptly as possible.

This person will be an editor at a publishing house. Agents are a point of entry for writers, but if they ever want their words to see the light of day, they need editors too – people who will acquire their manuscript for publication. The vast majority of mainstream editors don’t accept queries from authors, only from agents, who have honed their pitching techniques for years.

“From the outside, people may assume that we’re just sort of throwing spaghetti against the wall or something like that. That we’re indiscriminately blasting projects out there,” Barbara says. “But to me the pitch, the time when you call the editor and tell them about a book – that is where, if you put the right words in the right order, you can really set someone’s expectation where even by the end of the call you feel it. Like, ‘I’ve accepted it right away. I’m going to read it.’”

The rapport between agents and editors is perhaps the part of the literary industry that is the most remote from the general public, yet it’s one of its most important driving forces. It’s the kind of relationship built through regular phone calls, through lunches and coffees over the years. The goal for agents is to build a roster of editors whose tastes are familiar to them, so that they know who to call on a specific project. Editors, naturally, benefit from the process, too, since they heavily rely on agents to bring them new, exciting work.

“Part of what we’re trying to do as agents I think is really to get editors – and hopefully the editors trust us or they have a certain idea about our taste and what kind of books we work on – but, when we call and tell them about a book, I feel like I’ve done my job if I know someone is going to start reading,” Barbara adds. “So picking the right editor and the right way to pitch a book, to me, is crucial.”

The quest for the right editor will usually begin with a phone call – yes, an old-school phone call. If the publisher bites, the agent will then send them the manuscript and hope they read it promptly.

How does this all play out on the editor’s side? “We really rely on them to bring us the cream of the crop,” says Sally Kim, vice president and editor-in-chief of Putnam, an imprint of the Penguin Group. Sometimes, according to Amy Einhorn, executive vice president and publisher at Flatiron Books, a division of Macmillan, an agent will prepare a proper pitch, clarifying which kind of readers a manuscript is likely to attract, or comparing it to existing titles. Other times, she says, they won’t have a proper pitch other than “I love this novel and think you will too.” In some instances, Kim says, agents will even begin to entice editors before a novel is ready to send out – just to make sure they grab their attention as early as possible. As a result of this back and forth, a single editor working full-time will take on six to 10 novels a year on average, though this estimate depends on each imprint.

It’s well known that agents and editors alike receive an astonishing number of manuscripts. Kim, however, remembers a time when “it used to be an event to have a box land on your desk” following an agent’s call. But the increasing number of literary agents, combined with the fact that sending a manuscript now requires little more than an email and the click of a button, means that the volume has increased drastically over the years. It’s not uncommon for Kim to receive four to eight manuscripts a day – all quality work from agents she holds in high esteem.

How does an editor wade through a sea of quality work? It begins with knowing one’s personal tastes. “I usually know pretty quickly on if I want to keep reading or not,” Kim says. “Fiction is so subjective. So if I don’t click with it, it’s not a book that I’m going to be able to champion for the next two years of work with the author for five to six drafts.” In that case, she says, it’s fair to step aside so that the manuscript gets picked up by another editor. Above all, if a manuscript keeps her reading until the wee hours, that’s a sure sign that she should take it on.

Einhorn, too, knows what she’s looking for. “I’m always drawn in by the voice. If it’s a voice I’ve never heard before then I’m all in,” she says. “I tend to be less intrigued by what a novel is ‘about’ per se because to me it’s all about the voice.”

Pacing plays an important part as well – and a winning manuscript will, of course, omit neither style nor substance. “I always want a book that grabs me immediately,” Einhorn adds. “I have no patience for books where you have to read the first 30 pages before the story kicks in. It seems like too often submissions are either beautifully written with no story, or all story but the writing is lacklustre. What’s so great about someone like Liane Moriarty [the best-selling author of novels such as Big Little Lies] is that she does both – she’s a wonderful wordsmith with great stories. I think people underestimate just how hard it is to do both and do both successfully time after time.”

Sometimes, a manuscript will generate so much attention that multiple editors will express interest – at which point an auction will take place. An editor might make a pre-emptive offer to keep that from happening, or they might let the book go to auction. Once an editor acquires a manuscript for good, they begin working with the author, over the course of an editing process that varies with each writer. It can take roughly two years to take a book from acquisition to publication, according to Kim, with a year being the absolute minimum.

The author, meanwhile, will look for an editor who “shares their vision and is just as passionate as they are – if not more so – about the story they want to tell”, says Corinne Sullivan. “Editing is a long and tiring process, and so you need an editor who doesn’t just like your writing, but connects with your story, your characters, and you as a person as well,” she adds. “I knew early on that my ideal editor would be someone whose enthusiasm only bolstered my own. I knew that person also had to be someone who knew how to expand and improve my story in a way that felt true to my intention. It can be painful to be told, ‘Guess what? This isn’t perfect,’ but the right editor will make your manuscript reach its full potential.”

The editing process as described by Kim moves from a macro to a micro level, first addressing the general vision for the book, then eventually moving on to a line edit. “Some authors require lots of back and forth, some only want to talk to you once,” Einhorn says. “In the ideal world,” she adds, “the work an editor does goes completely unnoticed by everyone except the author. Our work should make a book better, but ultimately it’s the author’s work through and through.”

While this might seem like the end of the line, Kim warns this is actually the beginning of a book’s journey. “I think people think an editor sits at their desks all day reading. That makes me laugh,” Einhorn adds. “Editors are editing pretty much all the time except when they are in the office. When they’re at work they’re dealing with all of the other components of a successful book publication – marketing, publicity, cover design, interior design, contracts… And an editor is just one person on the publisher’s team that helps bring a book out into the world – there is an entire village of other departments who work on books.”

Publication day, then, is a long-awaited, joyful, nerve-wracking affair for everyone involved. “I have a book coming out next month, [Reed King’s dystopia] FKA USA, that was so many years in the making – I can’t remember how many now – and it will be a great moment when it’s out in the world,” says Barbara.

“Publication day doesn’t feel like an ending to me, though. I am usually a little bit worried. I wonder about whether all the reviews are in, if the author received his or her author copies, whether Amazon will go out of stock, the social media plans, the launch party, the tour if there is one. Then I just hope the book has a long, happy life, because I know how much the author has put into it and everyone who’s worked on the book is going to want it to succeed.”

The emotional roller coaster is naturally just as vertiginous on the author’s side. “After you sign a book deal, everyone assumes they’ll be able to purchase your book next week, but that is absolutely not the case,” says Sullivan.

“My publication date came a year and a half after I signed my contract, with dozens of rounds of edits and cover approvals and blurb requests along the way. Nothing compares to the feeling of holding a physical copy of your book for the first time. It feels like you’ve released something terribly private and vulnerable into the world that you almost immediately wish you could take it back, but once that fear passes, seeing that book in a store for the first time is the purest joy imaginable.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments