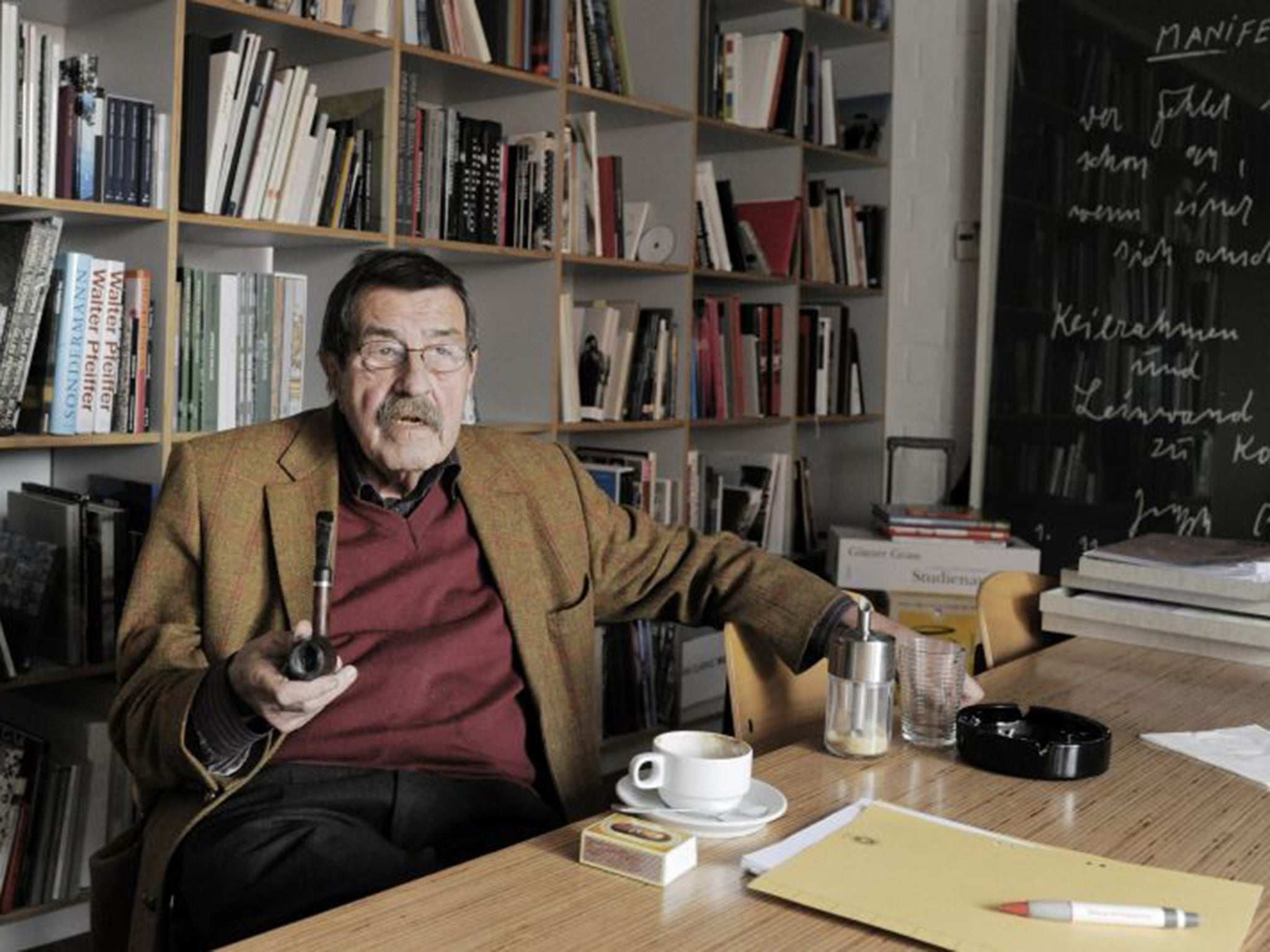

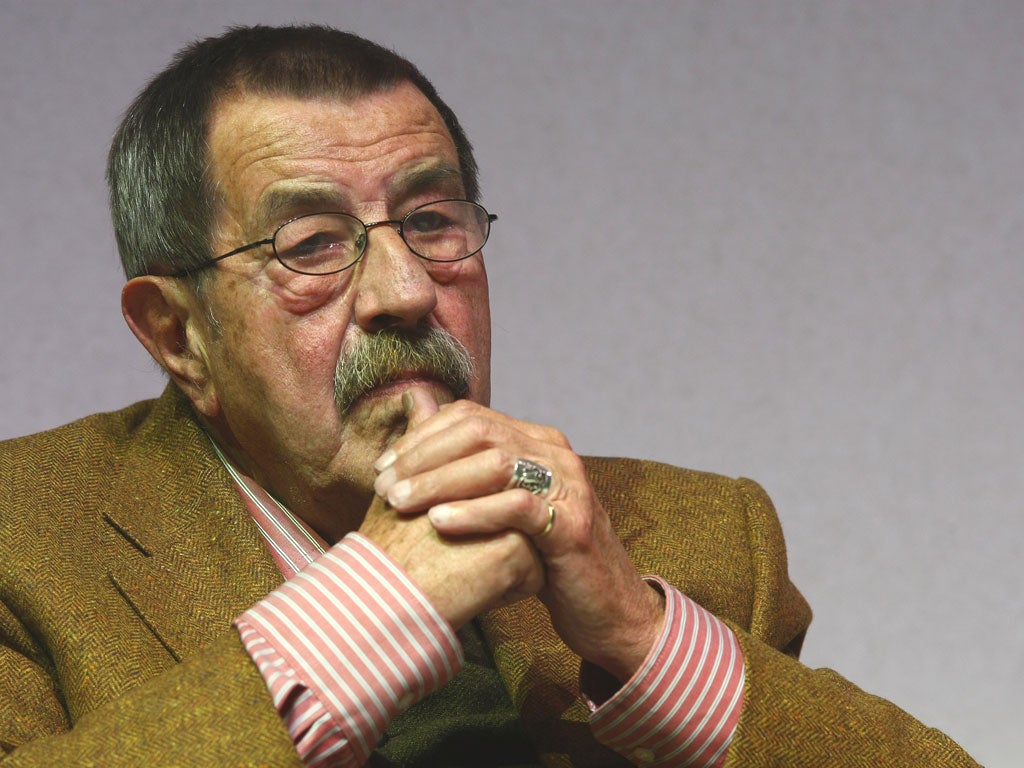

Gunter Grass dies: A literary giant who shone a fearless light into Germany's dark past

He left an inspirational stamp on two generations of novelists, from John Irving in the US to Orhan Pamuk in Turkey

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Günter Grass, the writer who shone a fearless light of truth into Germany’s dark past and found himself caught in its beam, has died aged 87.

The novelist, poet, playwright and sculptor, who in 1999 received the Nobel Prize in Literature, passed away in the Baltic city of Lübeck, near the farmhouse where he lived with his second wife, Ute.

Among the first of his literary disciples to pay tribute was Salman Rushdie, who hailed “a true giant, inspiration and friend”. Joachim Gauck, President of the Germany that Grass delighted, provoked and unsettled over 60 years, saluted an icon who “made the people of our country think”.

From his “Danzig Trilogy” of novels – The Tin Drum, Cat and Mouse and Dog Years – to later works such as The Flounder, Too Far Afield and Crabwalk, Grass did more than any other post-war figure to confront the pain of the past: both the Third Reich itself, and its legacy of division and denial.

Gunter Grass dies aged 87

Günter Grass attacks Merkel for Athens policy

Gunter Grass's Stasi files to be published

Gunter Grass berated for scorning united Germany

He was born in Danzig (now Gdansk in Poland) in 1927, the child of a German father and Polish mother. His parents ran a grocery shop, and he attended the local grammar school.

His membership of the Hitler Youth had long been common knowledge. But only in 2006, with the publication of the memoir Peeling the Onion, did his conscription in late 1944 into a tank unit attached to the Waffen SS come into public view. His revelation prompted bitter disputes, given Grass’s record of denouncing others’ silence. The teenage soldier, who never fired a shot, had yearned for victory – he wrote – thanks to “the stupid pride of youth”.

After the war, Grass trained as a stone mason and studied art in Düsseldorf and West Berlin. From the start, his writing had a craftsman’s heft and grain rather than an intellectual’s polish and balance.

His sensual, hands-on and defiantly plebeian outlook could make him a clumsy polemicist. Yet it massively broadened the appeal of his work. Part of the radical Gruppe 47 band of writers who spearheaded the renewal of West German literature, he first published plays and poems.

In 1959, his tragicomic epic novel The Tin Drum reverberated around the world. It became a turning point in the Germans’ reckoning with their past.

The tale of little Oskar, the traumatised witness to history who could not develop, helped Grass’s psychologically stunted compatriots to grow into a frank, adult dialogue about the Nazi era and the broken Germany it left.

He became an outspoken public figure, allied to Willy Brandt’s Social Democrats but never a party loyalist. Prickly and contrarian, impatient with consensus, he supported East German dissidents but later made waves with his attacks on quick-fire unification after the GDR collapsed in 1990.

In 1995, his novel Too Far Afield took issue with what he saw as a premature, one-sided togetherness. Then, in Crabwalk (2002), he added his voice to the recovery of the idea of German “victimhood”, with a novel about the loss at sea of almost 10,000 refugees after mass expulsions from east-central Europe in 1945.

During the 2000s, three volumes of lively and controversial memoirs confirmed his undiminished role as the thorny, quarrelsome conscience of his country.

Abroad, he left an inspirational stamp on two generations of novelists, from John Irving in the US to Orhan Pamuk in Turkey. They sought to emulate his candour, his courage and his exuberant mixing of turbulent history, wild imagination and page-turning narrative. Irving spoke for many when he wrote that “Grass remains a hero to me, both as a writer and as a moral compass”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments