Exotic England: A celebration of the nation's boundless curiosity with life beyond its shores

England has always been vibrant, curious, receptive and open

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In April 2010, I had coffee, at his request, with an English Defence League (EDL) sympathiser. He wore a good suit and shades, and wouldn’t tell me what his job was. After the first sips of cappuccino, he went off like a Roman candle. He tried to torch me, and I felt the burn. In sum, his beloved country has been a whore, open to “coloureds” and Europeans. Time passed very slowly. As I got up to leave, he grabbed my hand and admired my gold Indian bangles. He admired my Indian bangles. Even he, this raging, paroxysmal John Bull, surrendered, momentarily, to the glitter of the Orient.

It has been thus for ever. Queen Elizabeth I sought to banish “blackamore” slaves and servants from her isles. The same Queen keenly followed the fashions of Istanbul and ordered Londoners to come out with bells and torches to welcome luminaries from the Ottoman Empire. Putative “little England” erects ramparts, but her own sons and daughters breach the walls, sneak in outlanders, steal out to weird and wonderful places. This may be why the vast majority of migrants to the UK choose to settle in England.

Fate brought me to England and now I would not, could not, live anywhere else. Almost gone are those deep yearnings for Uganda, my birthplace, from whence I was exiled in 1972. It has been tough at times. Hostility to migrants, settlers and minorities pollutes the atmosphere, saps hope. But the nation’s open spirit, its liberalism and cultural litheness offset the negative ions. Most migrants to Britain can’t disentangle their convoluted emotions about a land that is duplicitous and yet remarkable, truly great. Many who want to belong cannot do so, because their overtures are regarded with suspicion or rejected. Yet every day, Englanders and outsiders reach out to each other, touch, trust, share, form ties that bind.

An Englishman I met at Bristol railway station saved me after my first husband ran off with someone else, leaving me bereft. He has cherished me and my son, whose father is, like me, a Ugandan Asian. Our daughter Leila is brown-skinned with brown eyes, but so, so like Colin, her blue-eyed English father. He is descended from old Sussex folk who’ve been roaming across the South Downs for ever, swimming in the wild sea, watching boats and pulling in outsiders from the cold, offering them warmth and piping-hot tea.

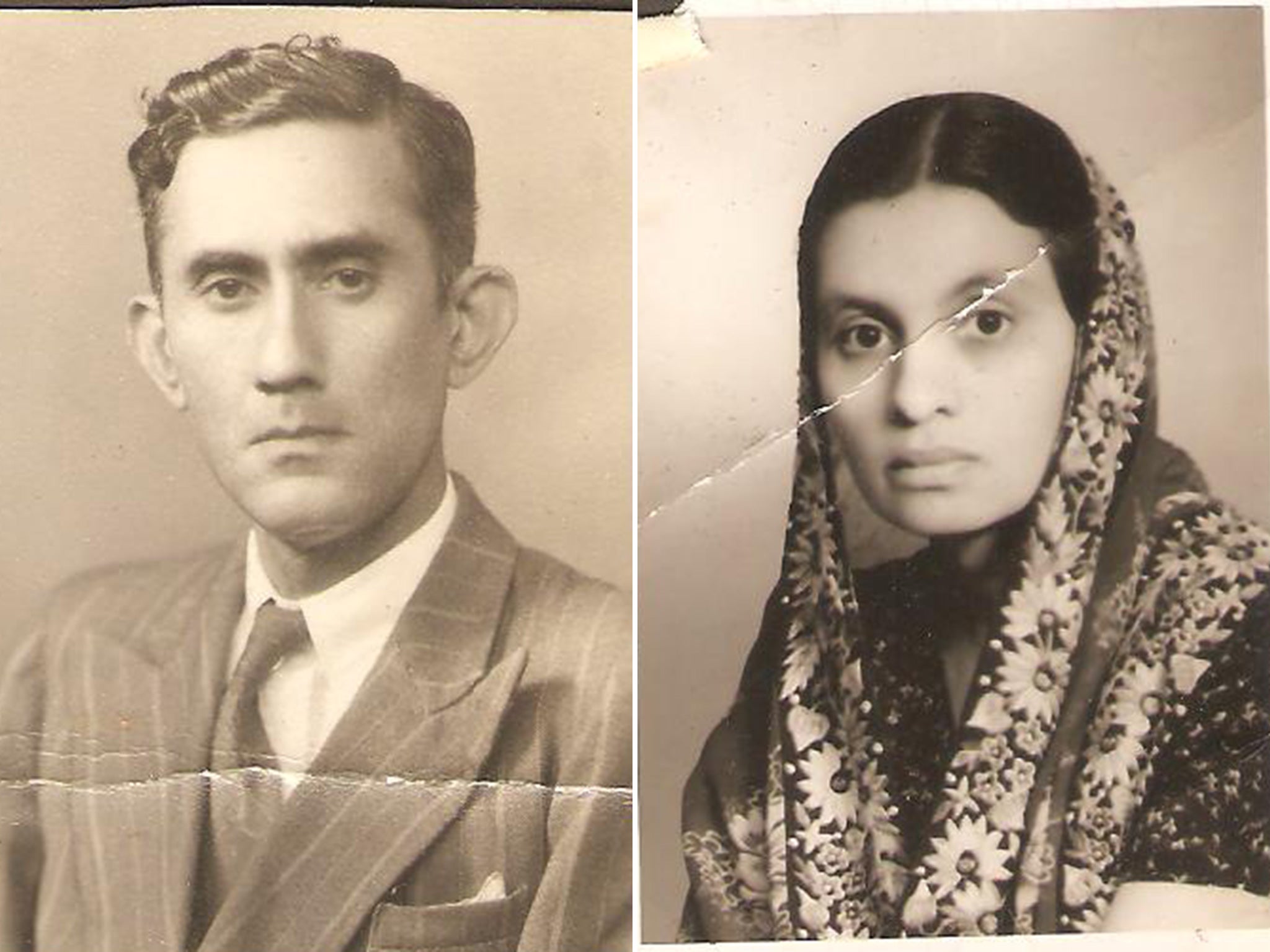

I was in Brookwood cemetery in Woking, Surrey, when I first thought of writing a book about my adopted country. My parents lie there, in the heart of England, under the vast redwood trees, where many of her own dead rest in peace. We, Shia Muslims, deemed sinners by strict Sunni Muslims, are kept out of their burial grounds. And so England obliges, provides plots for us and other minority religious sects. A mosaic of the dead. There is a mosque nearby – one of the first built in Europe after the Moors were banished from Spain. The architect, Mr WL Chambers, was English, as were the builders and many of the backers. What a tale of the unexpected this is.

My father, Kassam, an Anglophile, dressed like Graham Green and got me to read Shakespeare. He disowned me after I played Juliet in a school production. This Romeo was black. In Uganda, the races did not mix, not even in school plays. On my mum’s grave I laid her favourite pink English roses. After being expelled from Uganda, Jena never looked back. In her little housing association flat she felt safe and free for the first time in her troubled life. Though sometimes racially abused and threatened, her faith in England was never shaken.

When I first introduced her to Colin (who unwisely wore a hoop earring and a cerise pink shirt), she had stern words with me in Kutchi, our language: “Look at him. Long hair, dressing like a girl. First husband, one of us, betrayed you. You think this man will be better? The English are very nice people, best in world, but don’t understand family at all.”

Five years before her death, Jena wrote out a list of who should get her precious bits of jewellery. My English husband was to get a small diamond stud – she had lost the other. And in her last days in hospital, she instructed me to make sure Colin was one of her pallbearers. “He is more than my own son. He showed me so many places I never saw before in this beautiful country. He must hold the Kaffan [coffin].” This was her asking for the impossible: our funerals are intensely private and restricted to believers. But after secret meetings, the elders agreed. So the Englishman she had so mistrusted helped lay her down in Brookwood. And wept.

The English have been typecast (sometimes by Englanders themselves) as imperial snobs, dull, devious, duplicitous, rule-bound, cold, conservative, repressed, class-ridden, prejudiced folk. Their racism cuts and scars. But reel through their long history to now and you find they can be passionate, wanton, impulsive, infinitely curious and open. More so than hot-blooded Mediterranean and Eastern peoples or the other UK tribes. Their national dish is curry and their saint is from Syria, with skin as brown as mine.

Even as England formed itself, it included the world in its imagined entity. Its chutzpah came from thinking BIG, going beyond geographical boundaries and cultural fortification. Shakespeare audaciously named his first theatre The Globe. He never, apparently, travelled abroad, yet in Othello he created an irresistible outsider and in Anthony, a Western a warrior who could not resist the charms of the East. Anthony’s susceptibility is England’s susceptibility. The nation’s resolve dissolves before civilisations of excess and sumptuousness, strong flavours, intriguing outlanders. I see and know the melting ways of my compatriots.

Young, hot-headed Muslims are fixated on the Crusades or Colonialism, dark histories that left a stain and much pain in Muslim lands. But history is never black and white. Do any of them know, for example, that Winston Churchill gave Muslims the land in Regent’s Park where the huge Central Mosque now stands?

There have always been English renegades and turncoats who were enticed and nativised by the Orient. In 1599, the Sherley brothers from Sussex went off to the Persian court and became the Shah’s most trusted advisers and ambassadors; in the late 16th century, Samson Rowlie, aka Hassan Aga, was a powerful eunuch in the Ottoman court; Lady Mary Wortley Montague went to Istanbul in 1718 with her ambassador husband, Edward. There, as her letters attest, she felt liberated from the confines of her upbringing and circles. Turkish women, she thought, were happier and kinder than those back home. Harry St John Philby, father of Kim, a polyglot, explorer and Arabist, became a Muslim in Saudi Arabia in 1930, changed his name to Sheikh Abdullah and followed Wahabi Islam. The intrepid Gertrude Bell, who helped to create the nation of Iraq, is still considered a heroine by many Iraqis. Philby and Bell, like TE Lawrence, were also imperial spies and administrators, but the pull of the east disorientated their patriotism and identity.

Back in England, in the mid 1600s, Oxford and Cambridge established Chairs in Arabic and the members of the embryonic Royal Society learnt Arabic so they could study early Muslim philosophers and scientists. Playwrights and poets, artists, later novelists, too, were drawn to and inspired by the East.

That inclination remains strong. Prince Charles heaps praise on Islamic art, design and faith. Some fanatical Christians suspect he is a secret Muslim convert, at once dotty and treacherous. Princess Diana had two Muslim lovers, heart surgeon Hasnat Khan and Dodi Fayed. Undeterred by disapprovers, she let her heart go east. Diana and Charles were more alike than they realised. Their receptive and searching psyches were shaped by the divers streams and rivers of England’s history.

Imperiums succumb to the cultural caresses of those they overpower. Sex, love and friendship with the “other” prove impossible to resist. In the 17th century, Ottoman ships raided the English coast and took away fit men and women. King Charles II sent a Captain Hamilton to negotiate the release of captives, but many refused to come home. They had converted to Islam and were loving the Sybaritic life, noted Hamilton: “They had forsaken their God for the love of Turkish women, generally very beautiful.”

It was the same in India. The English encircled the world with a steely grip and the steel warmed up when touched. In the 18th century, upper-class Englishmen, and Scotsmen, too, took Indian wives and mistresses, lived like pashas. Empire historian Ronald Hyam believes that late British imperialism was partly driven by lust and desire. Here is one Captain Edward Sellon, writing from India in the 1830s: “… they understand in perfection all the arts and wiles of love, are capable of gratifying any tastes, are unsurpassed by any women in the world”.

It wasn’t all about hot sex. Some sons of empire found their soul mates in India. At the British library hangs a painting of a family in an English landscape. The wife is Muslim, the children mixed race, and he, William Palmer, a gentleman of some standing. The English diarist William Hickey (1749-1830), and several of his friends, had Indian “bibis”, common-law wives, whom they loved deeply.

Abroad, English men took up with non-white women, while back in England, until quite recently, the crossovers were largely between English women and men of colour. From 1578 to the 1970s, there were moments of high panic about these couplings, but they could not be stopped. Miscegenation is in the DNA of England. Why, even George Osborne’s brother, Adam, converted to Islam and married British Bangladeshi Rahala Noor. This land, apparently, has more mixed race relationships and biracial children than anywhere else in the Western world.

Food is an indicator of cultural conservatism or liberalism. Most Italians eat only Italian and don’t, in general, welcome diversity. Englanders are the opposite. Four years ago, in a posh hotel in Delhi, a chef proudly showed me a gorgeous tandoori oven bedecked with shimmering mirror tiles. “From England,” he said proudly, “with clay from Stoke, best quality.” To appropriate an Indian cooking appliance, add value and sell it back to the originators is a ballsy and entirely English thing to do.

To appropriate Eastern drinks and foods is even more so. Tea first appeared in England around 1658. By 1672, 13,000lbs were being imported from China. Englanders were hooked. Porcelain mania came next. A century on, perfect bone china was being made by Wedgwood and others. Tea and china became symbols of Englishness. Today, nouveau riche Chinese import English china for their tables.

English Crusaders hated Islam but loved Middle Eastern food. From the 14th century onwards, cooks in big houses used pepper, cinnamon, mace, cardamom, nutmeg, saffron, caraway, nuts and dried fruit. The chef Heston Blumenthal has recreated some of these dishes at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel. Of course.

In 1747, Hannah Close, a working-class woman wrote a cookbook packed with Indian recipes. Soon after, Sorlie’s warehouse in Piccadilly started selling curry powder, which could be ordered and sent by post. A woman called Sarah Shade went out to India in 1796, got caught up in wars, was imprisoned in Mysore, learnt to cook while in captivity, came back, and opened the first Indian takeaway in London. The story goes on. Thackeray wrote an ode and Queen Victoria was excessively fond of curries, but after the bloody Indian uprising, the dishes were given fake French names on palace menus.

Through the ages, some patriots – including the caricaturist William Hogarth – stood up for plain English food. They lost the battle of the senses.

English architecture, too, was influenced by the orient. When St Paul’s was being built, visiting Muslim dignitaries gave the workmen money because the dome looked like a mosque. What’s more, Christopher Wren thought Gothic architecture was Saracenic style refined by Christians. Fabulously rich, unhappy and unstable Englishmen created fantasy Eastern houses around England. Men such as William Beckford (1760-1844), son of a Caribbean plantation owner, who owned an Orientalist folly in Wiltshire and later a residence in Bath named Baghdad. Elizabeth Barrett Browning grew up in Hereford, in a Moorish style house with domes and minarets, built for her forbidding, discombobulated father Edward Moulton-Barrett.

Near Chipping Norton, in the Cotswolds, are two gorgeous Indian mansions built in the 18th century. Daylesford belonged to Warren Hastings, the passionate Indophile and Governor General of the East India company and the other, Sezincote, was owned by another company man. John Betjeman, wrote a poem to Sezincote:

Down the Drive

Under the early yellow leaves of oaks;

One lodge is Tudor, the other in the Indian style

The Bridge, the waterfall, the temple pool

And there they burst upon us, the onion domes

Chajjahs and Chattris made of amber stone

‘Home of Oaks’ exotic Sezincote.

The Brighton Pavilion is outrageous, really – built by the Prince of Wales, who became George IV, it is in the flamboyant Indo-Islamic style. My favourite place in London is Leighton House, home of the good Orientalist artist Lord Leighton. It recreates the beautiful old houses of Syria and Iraq, with fountains, blue green tiles and arches.

From bungalows to Arabian billiard rooms, to Turkish baths, Indian rooms, to Japanese gardens, Eastern design insinuated itself into English taste. Look at science, the theatre, past and present, language, art, and you find England the same secret embraces.

England stirs and is trying to redefine itself. It is defensive, jingoistic, Ukippy. But, this nation has always been vibrant, curious, receptive and open. It cannot now turn inwards and monocultural. Its own spirit and heart would not bear such limitations.

‘Exotic England: The Making of a Curious Nation’ by Yasmin Alibhai-Brown (Portobello Books, £20) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments