Drawing on Childhood: New exhibition examines why so many of our most cherished fictional heroes are orphans

From Oliver Twist to Harry Potter, literature celebrates looked-after children – why are we blind to real-life 'superheroes'?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Children’s books are bursting at the bindings with thrilling secrets and concealed wonders. But there is a paradox presented within an overwhelming number of them that is hidden in plain sight. The real mystery, in fact, is why we never see it.

Think of Rapunzel, David Copperfield, Pippi Longstocking, Heidi, Heathcliff, Superman, Spider-Man, the tale of Romulus and Remus, Tracy Beaker, Tom Sawyer, Harry Potter, Oliver Twist, Cinderella, James and the Giant Peach, Anne of Green Gables, Mowgli in The Jungle Book, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Sophie in The BFG, Lyra in His Dark Materials, Babar, Paddington Bear, Pip in Great Expectations, A Little Princess, Jane Eyre, Annie and Martin Chuzzlewit. The list goes on, and on...

Many of the most powerful characters in our best-loved stories are orphaned, adopted, fostered or found. At the same time, many of the most powerless citizens in our society are orphaned, adopted or fostered children, and the marginalised adults that so many become.

Why have so few of us even noticed this centuries-old disparity? It is an oversight that infuriates the poet Lemn Sissay, who was adopted in all but name at a few months old, before being abandoned overnight, at the age of 12, by the people he regarded as his parents and sent to a series of children’s homes.

“We all empathise with these characters and want to see them win out. And at the same time, none of us wants a children’s home at the bottom of the street. So there seems to me a lie,” Sissay says indignantly, “between how society recognises the hero in popular culture and makes the child in care invisible. And we doubly offend by not making the connection. So why are people not seeing it?”

The thought sparked a poem that is now emblazoned across the walls of the café at the Foundling Museum in central London. In “Superman was a Foundling”, Sissay relays the umpteen characters across our cultural landscape who have had “alternative childhoods”.

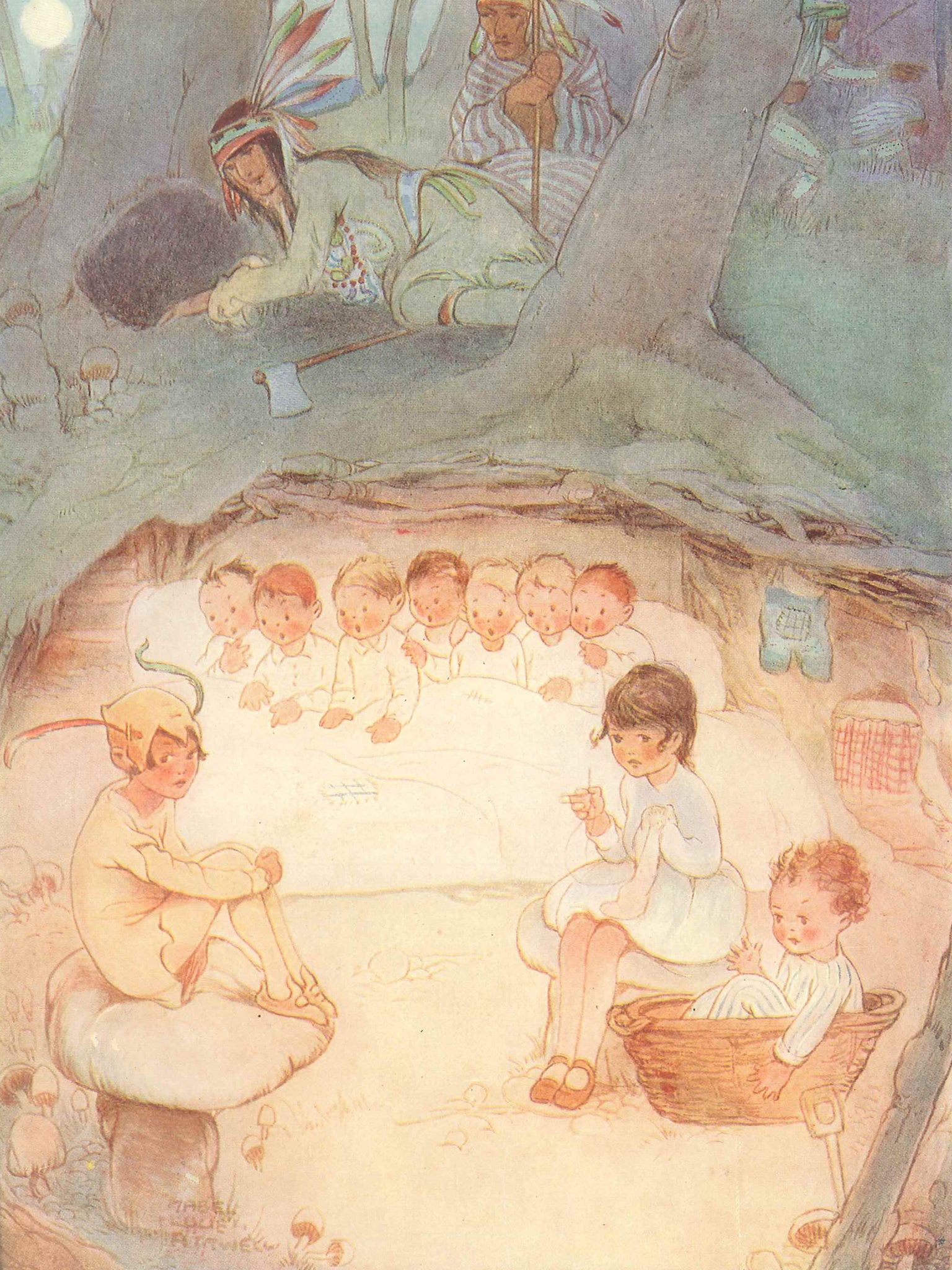

In turn, the mural proved the catalyst for an exhibition, Drawing on Childhood, which opens at the museum later this month, exploring looked-after children in literature and illustration, from the 18th century to the present day. It starts with Henry Fielding’s novel The History of Tom Jones, A Foundling, first published in 1749. Three artists, Chris Haughton, Pablo Bronstein and Posy Simmonds, have been commissioned to produce new illustrations inspired by the book, which will feature alongside loaned works by the likes of Quentin Blake, George Cruikshank, Thomas Rowlandson and David Hockney.

The Foundling Hospital was the UK’s first children’s charity when it was established in 1739. It was the country’s first public art gallery, too, after the painter William Hogarth encouraged many of the leading artists of the day to donate works.

The institution appears prominently in many of the books featured in the new show. The curator, Nicola Freeman, explains: “Dickens, who was very involved in the hospital, lived close by and incorporates it into his work – Tattycoram in Little Dorrit is actually from the Foundling Hospital and named after Thomas Coram, the founder. JM Barrie would have overlooked the hospital and that flat was where he based the Darlings’ apartment – where Peter Pan would have flown in. And then we finish with Jacqueline Wilson’s Hetty Feather, who was also in the Foundling Hospital.”

Freeman doesn’t claim to want to overhaul attitudes with the exhibition, treating the works with an academic detachment (“We are just working with the material”). But Sissay certainly does.

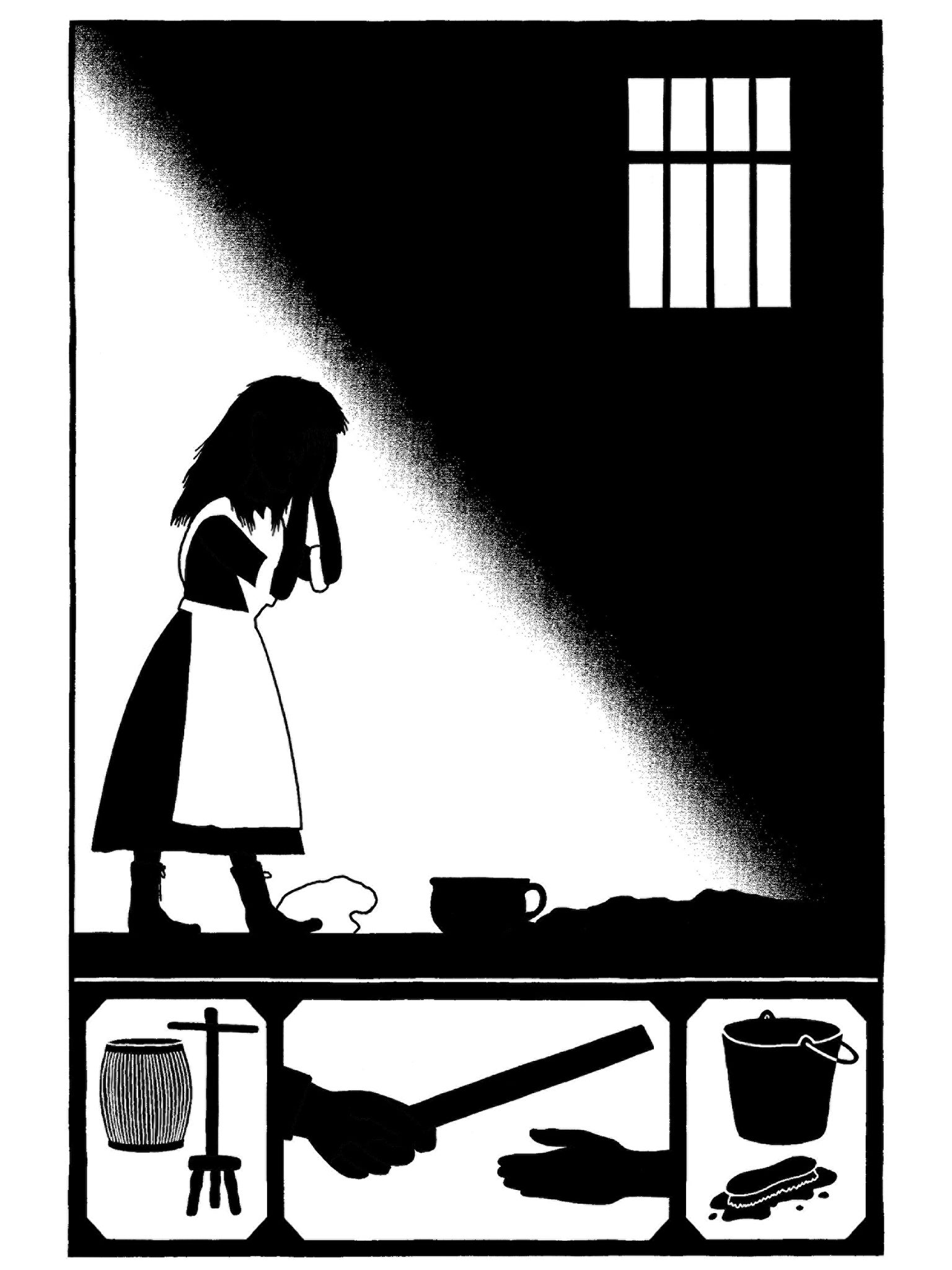

Superman was a foundling, he says in his poem. But he believes that all youngsters who have been through the care system have to employ superhero levels of empathy, courage and resourcefulness to survive. “Children in care remind me of the X-Men,” he says. “They self-harm and it is almost like: I can make fire but I burn myself. I can go invisible but I find myself lost. Children in care are four times more likely to commit suicide, and it is superheroes turning in on themselves.

“I’m deadly serious about the superhero thing, it’s not flippant. It’s my ambition that one day throughout Britain, people will not be able to think of a child in care without somewhere associating in their minds, ‘Oh, that’s like superheroes’. But that’ll take a lifetime.”

Of his own experience, he muses: “I always felt like a superhero. I learnt that there was so much untruth around me that I had to feel how people were rather than listen to what they were saying. And so I was like Lisbeth Salander, in The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo. I was in situations where I could trust nothing around me so I took how I felt to be gospel and that was my kind of superhero skill. I always knew that I had something unique that couldn’t be taken away from me and that everything that was happening to me was trying to take it away.”

Removing parents from a story in order to place the child – and their adventures – at the heart of a book is clearly a useful and common dramatic tool. “Heroes ought to be unsupervised,” is how Daniel Handler puts it (you’ll know him better as Lemony Snicket, author of A Series of Unfortunate Events, 13 books that follow the lives of the Baudelaire orphans).

To Lauren Child, author and illustrator of the Charlie and Lola books (where the parents are never seen) and That Pesky Rat (about a rodent living in a bin and searching for an owner and a home), the absence of parents is a literary device. “Get rid of the parents or adults, so the story can take off and there’s more jeopardy and more drama,” she says.

But Anthony Horowitz, author of numerous books about orphans, most notably the Alex Rider series, bristles at the mere mention of the phrase “plot device”. “What it does is it puts children into a world in which adventure can happen, but that’s not just a plot device,” he says. “It absolutely goes to the heart of what children’s literature is about.”

Michael Morpurgo, former Children’s Laureate and author of War Horse, has just returned from a visit to the “jungle” refugee encampment in Calais, where he met an Egyptian boy of 12 “on his own in the world”. “I have no idea whether I’ll write his story, but it’s the kind of story that really interests me because you find out so much more about how a child sees the world that way.”

Neither our preoccupation with orphans in literature nor their neglect at the hands of the state is anything new. “I think that the way we treat children in care is particularly British, and particularly connected to Victorian times,” Sissay says. “If you’re in a workhouse, you will be provided for; and you must work; and you must repent; and you are illegitimate.”

All you need to do is open a Victorian novel and you will find “at least one orphan, if not half a dozen in there”, says Professor Laura Peters, head of English and creative writing at the University of Roehampton. “I started thinking: ‘Why?’ In the Victorian age, the whole concept of the family really became the kind of building block of society and everything was structured around it, with Queen Victoria as the mother figure presiding over this one large family – the Empire. If you were born outside of that, then it raised a lot of problems for society and a lot of concern of what to do with you.”

But Professor Peters, author of Orphan Texts: Victorian Orphans, Culture and Empire, traces an even longer literary tradition. “If you go back to the Romantics, they felt that orphans were in a sense a figure fresh from God. There’s a poem by Wordsworth called Ode on Intimations of Immortality. He talks about ‘trailing clouds of glory’ – they just felt that these children had a spiritual power, were unsullied by an earthly genealogy, so therefore they had a kind of redemptive power, a spiritual status. The Victorians picked this up and saw this as a potentially artistic and creative status as well.

“If you go forward today to something like Harry Potter,” Professor Peters says, “I think you see a strong legacy. He’s orphaned but he’s got special powers and he’s going to overcome the evil. And you can see a bit of it in James Bond, actually, if you look at the books. It is that idea of a kind of redeemer-like quality.”

However, a sense of stigma and shame was entrenched, too. In Silas Marner, George Eliot writes: “No one knew where wandering men had their homes or their origin; and how was a man to be explained unless you at least knew somebody who knew his father and mother?”

“When you hear about the worst of the cases in the media today, then you think, gosh, it’s not much different from the Victorian era,” Professor Peters says. “There is still, I think, probably a residue of blaming the victim. It does feel somehow that this aspect of society hasn’t really moved forward perhaps as much as one would have hoped.”

What also remains is the gulf between fact and fiction. Morpurgo dubs it a “comfort separation”, and says that “often, people forget that these stories are based on lived-through horrors and terrors”. Child argues it is “a sort of defence mechanism, a way of guarding against having to imagine. It’s much easier”.

For Sissay, it is indicative of a deeper malaise. “People have always been going into care, since Moses, so why are we ashamed of it? When a child goes into care, they are physical proof that the system of family that we all go around promoting, we’re living proof that’s not true. So, anthropologically, I think, the family is doing everything it can to not admit that that happens, and all of that responsibility then falls on the child. Isn’t that weird: you get adopted, you go to dinner parties when you’re older and you don’t want to mention your past because somehow it will spoil the fucking party. And at the same time, people will then go and read Harry Potter to their children.”

He argues passionately that our care system should be so good “that middle-class parents are fighting to get their children into care – like schools. When a child comes into the state, the state should be saying, ‘now you’re OK: we’ve got the best education and training, the best therapy, and there will be no bars on us looking after our child’. But that doesn’t happen because I don’t think this society is ready to make a care system that shames the family.”

Instead, in the words of David Cameron at his last Conservative conference speech, we have a care system that “shames our country” – setting children up for “the dole, the streets, an early grave”.

The powerful stories contained in these books may not have changed this, but they can often provide succour to looked-after children – and even to their new parents. Jacqueline Wilson, author of the Tracy Beaker books (about a girl living in a children’s home) and another former Children’s Laureate, who has sold 35 million books in the UK alone, says: “I’ve been moved to tears sometimes by letters, emails and conversations in person with young people who have been brought up in care and who have found Tracy Beaker an inspirational character, not because she’s well-behaved or high-achieving – she’s certainly not – but because she doesn’t let authority grind her down. They don’t use the word cathartic, but I think that’s what they mean. And for children living in very loving families, I think it’s good to realise that not everybody can lead the sorts of lives that they have.”

Handler says: “What has surprised me is that orphaned readers have found the books engaging – an audience I never thought I would court. It seems that orphans are haunting and interesting even to orphans.”

Child hasn’t found this yet with her five-year-old daughter, Tuesday, whom she adopted in Mongolia. “We all tune into different things. It just so happens that my daughter is completely fascinated by cosy things about families.” The author says for child and parent, “any book can be of great worth in that sort of situation because so much is just about kindness, putting yourself in someone else’s shoes, thinking about what may have happened before you were there. And that’s what I think about a lot. You want them to understand that you share in that loss that you weren’t with them right from the very beginning. I know that’s a thing that really haunts me”.

I ask Morpurgo if it is dispiriting for a children’s author to see how little the stories we tell have transformed the reality we live. The prime minister admitted in that conference speech that 70 per cent of prostitute women were once in care and 84 per cent of care leavers finish school without five good GCSEs.

“It does bring change, that’s the truth of it,” is his reply. “We can go back to Dickens – for reasons of his own, he wrote a great deal about the poverty of people and children in particular in the streets of London. At some stage, whether it was Hogarth or whether it was Dickens, we changed. We decided that this was not a way that people should be.

“Writers and poets and artists and dramatists are there to remind us of these things. I mean, if in fact you are simply writing a story for entertainment, then you shouldn’t be doing it. I think it’s important for me certainly that whenever I write a story, it is a cause in some sense and I’m quite sure Dickens felt that when he wrote Oliver Twist.”

So when politicians sit down to read their children a bedtime book tonight, Morpurgo hopes they uncover a deeper meaning. “When they are quite vulnerable themselves and they are reading a story that matters to them, they can get, I’m sure, quite tearful and engaged with it,” he says. “Yes, these things can nudge us and change us. If you don’t come away from a story thinking harder, then the story hasn’t worked. Literature is the way we learn to empathise. I don’t know another way that we learn empathy better than in a book or in a play.”

A study carried out by Italian academics in 2014 found that reading Harry Potter helped primary school pupils to become more empathic and “improved attitudes toward stigmatised groups”.

Sissay is convinced we will all eventually be consciously “making that connection” between the hero on the page and the traumatised but “emotionally gigantic” hero in care. “It’s too obvious to not look at,” he says. “So once you see it, you can’t not see it.

“With so much evidence to connect heroes of popular culture with the child in care, the question ‘why has that connection not been made?’ is the most revealing of our prejudice towards the child in care. It is serious. Where the prejudice leads is very dark... Jimmy Savile.

“Dickens saw it all very early on. The reason we’ve not made this connection is because of never seeing the foster child as a good thing in their own right. As intrinsically good.” µ

‘Drawing on Childhood’ opens at the Foundling Museum on 22 January; foundlingmuseum.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments