‘How is this not the norm?’: The campaign to make picture books accessible to visually impaired children

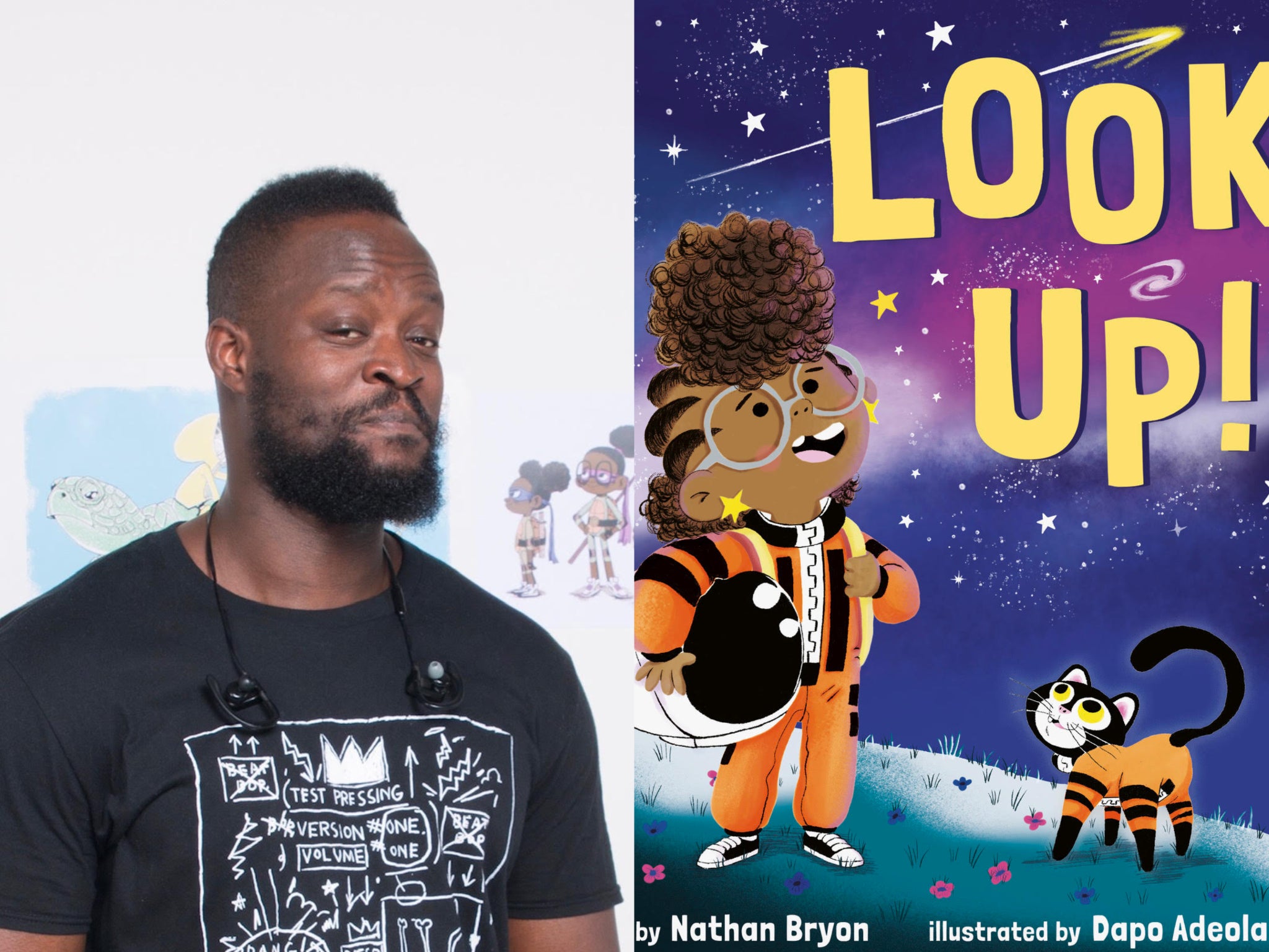

For many of us, picture books are the entry point for a life of reading – but for blind and partially sighted children, they remain inaccessible. Illustrator Dapo Adeola tells Ella Kipling about his campaign to change that

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mr McGregor chasing Peter Rabbit away from his crops. The curved talons and bright orange eyes of the Gruffalo. The Very Hungry Caterpillarmunching its way through a colourful meal. Picture books have given many of usour most evocative childhood memories, but for an estimated 37,000 blind and partially sighted children in England and Wales, the chance to tumble through brightly coloured pages into different worlds is just out of reach.

Picture books are not published in an accessible format for visually impaired children. Although braille books exist, there is no way for children to enjoy the illustrations, unless they are raised and created in a 3D fashion, a process that remains rare in the publishing industry. This is why award-winning illustratorDapo Adeola has spent eight months campaigning for his books to be adapted.

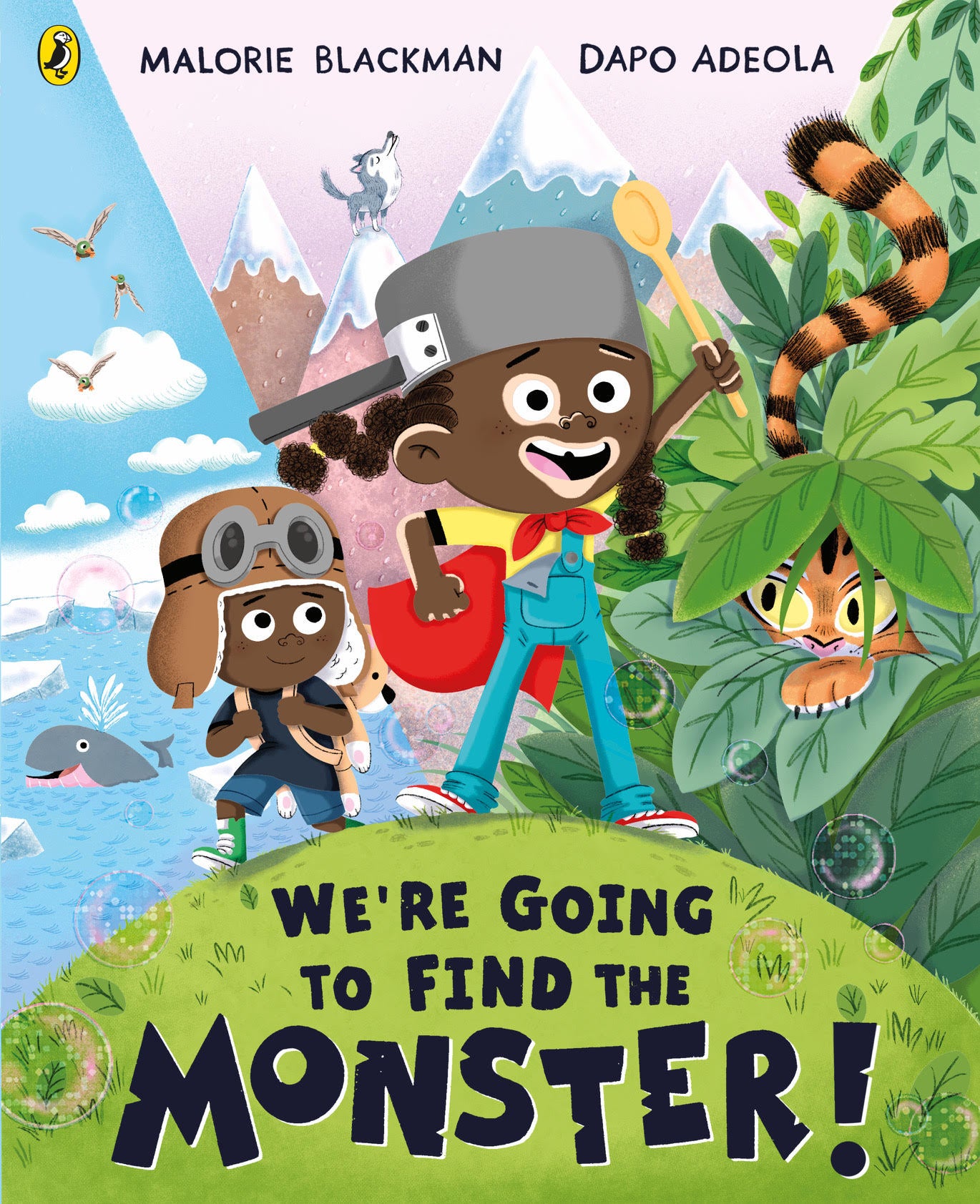

This year, millions of children have been reading We’re Going to Find a Monster, written by Malorie Blackman and illustrated by Adeola. The story was chosen as the BookTrust Time to Read in November and every reception-aged child in the UK was given a copy for free.

However, aware of the lasting impact story books can have, Adeola is pushing for even more access to his books so that as many children as possible will be able to enjoy his drawings, including those with visual impairments.

After launching thecampaign in March, Adeola – who was namedthe British Book Awards’ Illustrator of the Year in 2022 – has finally hit his fundraiser target, collecting enough money to transform several of his books into tactile audio-visual experiences.

Adeola knew little about the experience of visually impaired children before Living Paintings, a charity, reached out to him with the aim of adapting his books. “I thought books were available in braille, and that was enough, I did not have the knowledge or the education on the spectrum of visual imparity. I didn’t know anything about that,” he says.

Now, however, the illustrator does not understand why more is not being done to tackle the issue. “How is this not the norm? Why is it that we even have to raise money for this?” he questions.

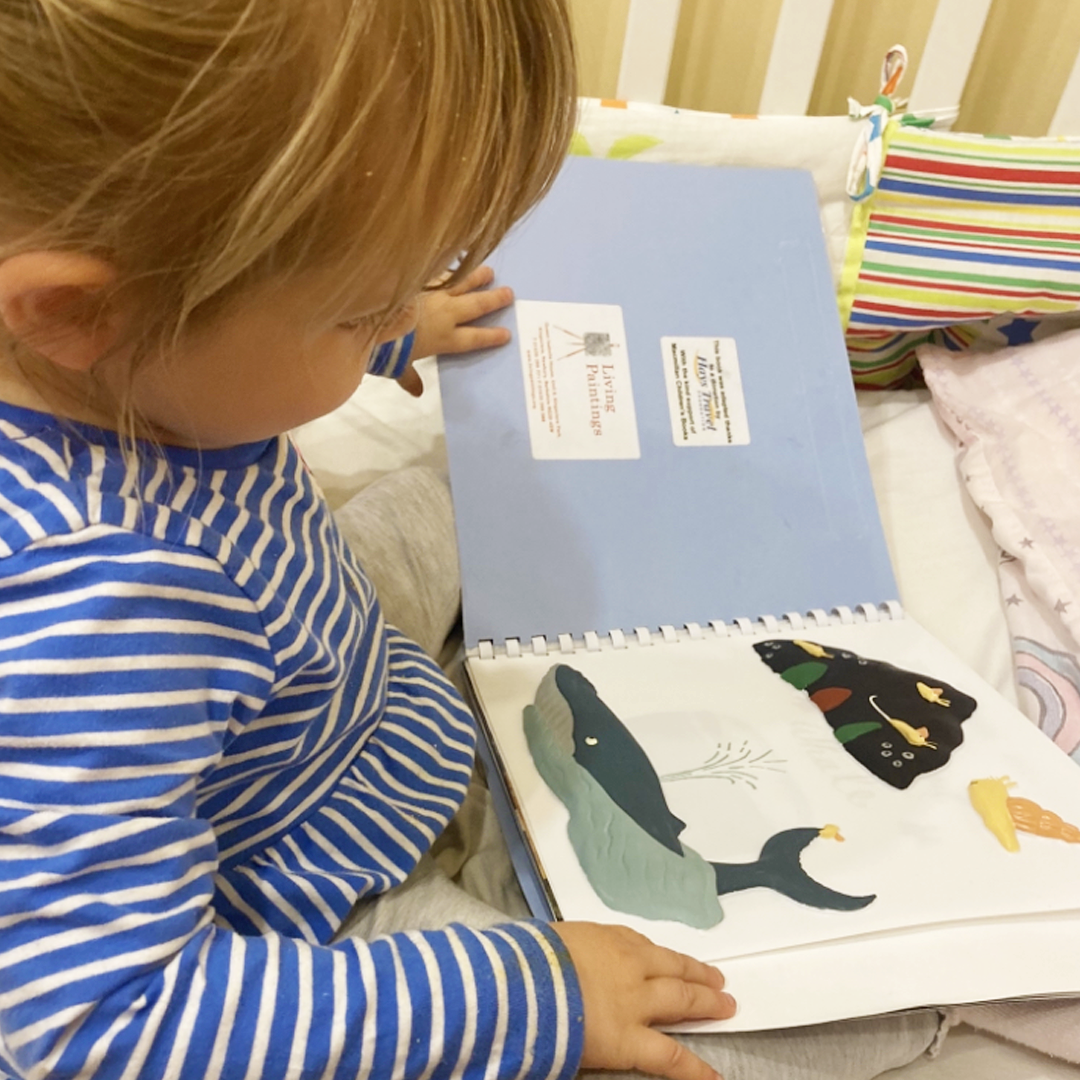

Poring over picture books and delving into a story gives children their first glimpse into different worlds, as well as a greater understanding of our own; the illustrations and words work together to tell the story. This hybrid experience of literature and artwork helps to improve children’s literacy skills and vocabulary.

It’s something that visually impaired children, who rely on touch and sound to engage with the world around them, are currently missing out on.

Living Paintings, a charity which transforms picture books through art and sound to make them accessible, are working to tackle the problem.They take each illustration from a book and turn it into a raised tactile element so that children can experience the story and the artwork themselves, rather than just have it read to them.

The process begins with volunteers who trace each illustration. These are then carved out of wood by another volunteer to create the master artworks. After this, a thermal press is used to create the raised pictures out of plastic before they are hand painted.

Braille is added and an audio guide is recorded to accompany each book, whichbothnarrates the story and tells the children what they are feeling on each page. Stars including Imelda Staunton and Ethan Hawke have lent their voices to the cause.

Together, these elements are all vital in creating an engaging reading experience for visually impaired children as well as their family members.

“[We] give them that experience of reading a book and togetherness. It’s a benefit for the family as well,” Nick Ford, head of marketing at Living Paintings explains. “I think every parent has this image in their mind of sitting and exploring picture books during story time together. This allows them to do that.”

Every one of these accessible books, of which there are around 200, is available for free through the charity’s online library. Titles include My Monster and Me, My Pants, Tiddler, and classics like Spot the Dog, The Snowman, and Elmer.

One child, Teddy, has been borrowing books from Living Paintings since he was a baby. Now, at six years old, he is able to read braille thanks to the skills he learnt through engaging with the tactile picture books.

Ford recalls the day those at Living Paintings saw him reading alone for the first time: “That was a really proud moment for us because we’ve been supplying him with books since he was a young boy.”

He has been developing a love of books that a lot of blind children miss out on. “There might be this kind of misconception that picture books aren’t for them,” Ford says.

Adeola adds: “So many of us that didn’t have access growing up, that aren’t even visually impaired – it’s impacted how we’ve grown up. So I can only imagine what it’s like for kids who have that extra hurdle to overcome. As much access as can be possibly given is massively important.

“As adults, we become conditioned to downplay things like children’s books, ‘it’s for kids, it’s how big of a thing is it?’” he says.

“It’s a huge deal. It’s a huge deal to kids, so it does matter.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments