The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Daniel Kehlmann’s new book uses humour to try and navigate the toughest of times

The author and playwright talks to Tobias Grey about his new book ‘Tyll’, Donald Trump, and using the impish humour of his character, jester Tyll Ulenspiegel, to find a way through the world’s hardships

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Daniel Kehlmann read the news that former Nissan executive Carlos Ghosn, facing financial misconduct charges in Japan, fled the country in a box, he couldn’t help but feel a twinge of admiration.

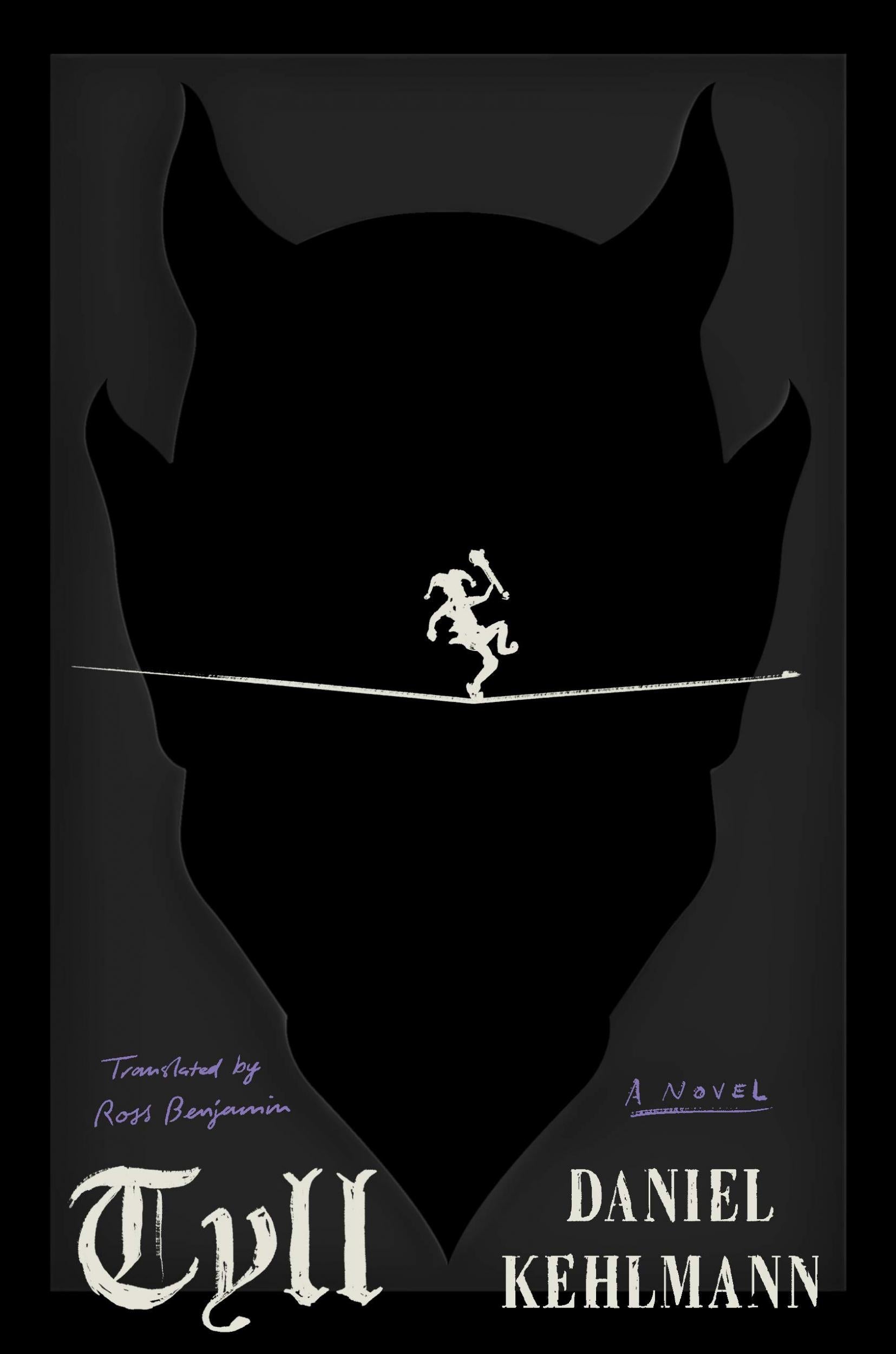

It was the kind of caper that he might have written into one of his novels, where escape artists, pranksters or con men often outwit their adversaries. For example in his latest book, Tyll, which Pantheon will publish in an English translation by Ross Benjamin on 11 February. It has sold nearly 600,000 copies in Germany since it was published there in 2017 and is being adapted into a television series by Netflix.

Tyll transmits the 14th-century tale of jester Tyll Ulenspiegel about 300 years into the future, plopping him into the Thirty Years’ War. Tyll travels through a Europe devastated by conflict, encountering fraudsters, soldiers and royalty, including Queen Elizabeth of Bohemia, whose love of Shakespeare chimes with Tyll’s own sense of theatrical spectacle.

Kehlmann’s eighth novel and the sixth one to come out in English, Tyll is also his second book of historical fiction, following his 2005 bestseller Measuring the World. Tyll has either been or is being translated into more than 20 languages. But for a long time it was a novel that Kehlmann, who turned 45 in January, was reluctant to write.

“It might sound very weird now, but I actually don’t like historical novels,” he says. “When I wrote Measuring the World, I told myself: ‘This is an experiment, I’m never going to write another historical novel.’”

Measuring, which is set in the late 18th century, follows the adventures of two historic Germans – naturalist Alexander von Humboldt and mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss – as they set out to measure the world from its highest mountain to its deepest cave. With Tyll, Kehlmann envisioned something darker, about wars of religion and the impotence of statecraft.

“In a way, it’s a serious literary experiment in trying to imagine what the world was like before the Enlightenment,” he says. “What it was really like to live in a world before Voltaire, Newton and all these people. It’s great to write about, but of course you wouldn’t want to spend even an hour in this world.”

At one point, Tyll goads the residents of a German village to take off their shoes, throw them into the air and then reclaim the ones that belong to them – watching with amusement as a brawl ensues. “I was about 7 years old when I heard this story at school, which was presented to us as something didactic as if Tyll is showing people their folly,” Kehlmann says. “But that’s not true. The only thing that story actually demonstrates is that everyone had the same kind of shoes, and he’s just being a really mean prankster.”

The idea of a jester character appealed to Kehlmann, he says, “because he’s someone who could go anywhere and meet anybody at a time when there was not much social mobility”.

Tyll took him five years to write, twice as long as any of his other novels. Kehlmann was about two-thirds of the way through when Donald Trump was elected president in 2016. Kehlmann, his wife, human-rights lawyer Anne Rubesame, and their son, Oscar, live in Manhattan, after years shuttling between New York and Berlin.

I was always captivated by stories of escape, especially escape by means of tricks and brilliance of the mind

“When Trump won, I was so shocked and worried that for a while I couldn’t write anymore,” Kehlmann says. “But then I thought of Tyll’s resilience and his way of making fun of anything. It was revelatory because I’d never had any experience of my own character helping me to finish something or to cope.”

One of Kehlmann’s hallmarks as a novelist is the impish humour that he injects into bleak and absurd situations. It is there in Tyll and Measuring, but also in his modern-day novels, such as Me and Kaminski (2003), Fame (2009) and F (2013), where the vanities of artists, actors, writers and businessmen are exposed by their appetite for outlandish quests.

“His fascination for comic writing is very unusual in German literature nowadays, especially the way he combines it with elements of horror,” says Alexander Fest, Kehlmann’s longtime editor at his German publisher Rowohlt Verlag. “I think he grew fascinated by Tyll Ulenspiegel because two of the things he’s interested in came together in this one character. Tyll is an uncanny figure in the way he makes fun of people and is funny – not for the people he makes fun of, but for the others standing around.”

Kehlmann, who was raised in Vienna, credits his Austrian roots for this sensibility. “There is quite a lot of comic literature in Austria which didn’t travel a lot because the canon of German literature is still very much formed by northern Germany,” he says. “My growing up in Austria gave me a certain distance from the funny side of German culture, and the ability to make fun of it that maybe I wouldn’t have had if I’d grown up in Berlin.

He studied philosophy and German literature at the University of Vienna but was more interested in Latin American magical realists like Gabriel García Márquez and Mario Vargas Llosa. “I was always captivated by stories of escape, especially escape by means of tricks and brilliance of the mind,” he says.

Part of this fascination also stemmed from the experiences of his family during the Second World War. His paternal grandparents were assimilated Austrian Jews who survived thanks to forged documents that disguised their identity. His father, Michael, was imprisoned in the Maria Lanzendorf concentration camp but was released about a month before the end of the war.

Michael Kehlmann went on to have a productive career as a TV and theatre director. Daniel Kehlmann regrets that his father never got to read Measuring the World, as he was suffering from dementia and died two months after it came out. But without knowing it, a baton had been passed. While Michael Kehlmann was alive, his son never considered writing for the theatre.

“I always felt like theatre was my father’s world, so I didn’t want to get close to it,” Daniel Kehlmann says. “But when I wrote Measuring the World, one of the upsides of writing a big bestseller was that it freed me up to try out many things.”

He recently completed his fourth play, The Voyage of the St. Louis, about Jewish refugees who left Germany in 1939, were refused entry in Cuba and the United States, then turned back to Europe. Later this year it will be performed as a BBC radio play in an adaptation by Tom Stoppard.

For Kehlmann, the new play feels like a corrective. German fans for years congratulated him on writing books that had no relation to Nazi Germany. “I told them that I knew where they were coming from, but I didn’t set out to be official proof that we have left that past behind,” he says. “We haven’t, and we shouldn’t.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments