Cooking up a storm: John Irving's latest saga reveals the secrets of authors and chefs alike

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.John Irving, who never gives short measure, treats the readers of his 12th novel to a double master-class in the arts of writing – and of cooking. As stuffed and spiced with the pleasures of slow-roasted plot and savoury digression as any of his books, Last Night in Twisted River (Bloomsbury, £18.99) can with equal relish argue that "rewriting was writing" against the purveyors of "first-draft gibberish" and disclose the secret ingredient for perfect pizza. It's honey. "I made pizza dough for years and years, and honey was a late discovery," says the creator of generously-portioned bestsellers, whose prowess in the wrestling ring has until now overshadowed his gourmet side.

Even here, you feel that Irving loves to practice, to compete and to excel. He once met Julia Child, headmistress in culinary arts to baby-boom Americans, in a food store with high shelves in Cambridge, Massachusetts. "I was reaching for a box of cereal or something, and this very tall woman came up and said, 'May I help you?'. I told her I'd read all her books and loved them. She didn't pretend to have read mine. But she said, "Oh, my husband has read all of you.' So I spontaneously invited her to dinner. It went alright."

Twisted River swarms with a record-busting profusion of lovingly described dishes, from the sweet banana bread served to hungry loggers on frozen forest mornings to the "sauce grenobloise, with brown butter and capers, for the chicken paillard" on the menu of an upscale restaurant in a Vermont town. Recipe by recipe, revelation by revelation, the barnstorming tour de force of an opening section – set amid the many perils of the New Hampshire logging camps in 1954 – gives way to an unspooling tale of family lost and found, of retribution and reparation.

Via a cousin in the logging business, Irving tracked down veterans of an almost Homeric way of life, of feats and feuds in a "world of accidents" where death stood no more then a torpedoing tree-trunk, a cracking ice-sheet or a bar-room brawl away. "These men – they didn't just survive a very rough way of life. The drinking, the diet was so self-destructive. Most of them smoked and drank themselves to death if they didn't die in the rivers." It took effort to find an old-time log-driver alive, alert and literate enough in English to read Irving's manuscript – many in New Hampshire were French-speaking Quebecois. Meanwhile, he unearthed the buried remnants of transient townships on sites where steam-powered logging engines still sit and rot deep in abandoned woods: "It is like finding the skeleton of a dinosaur."

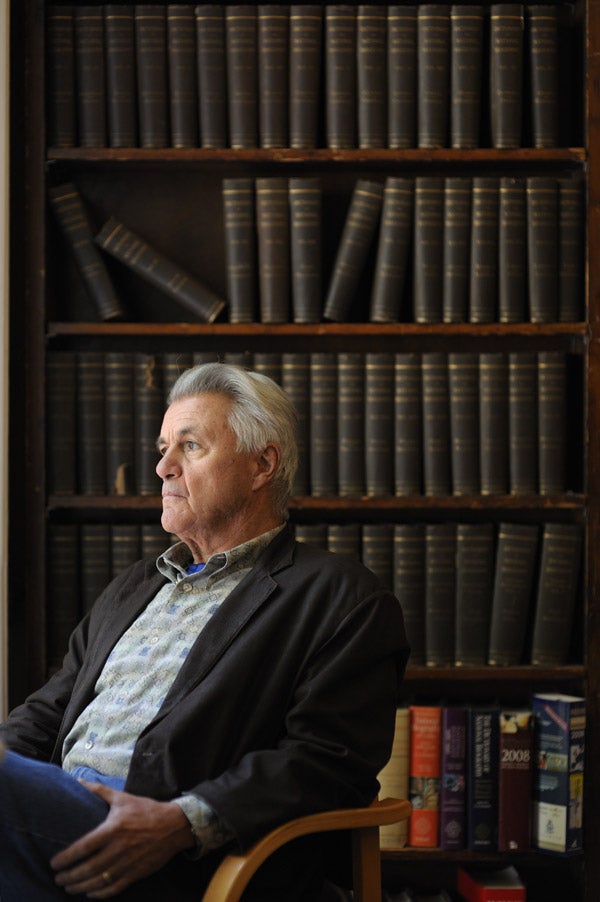

"This novel has been in the back of my mind longer than any other I've written," Irving explains in a book-lined room of his publisher's Soho offices. Now 67, a beloved fixture of the American – and global - literary landscape over the 30 years since the success of his fourth novel, The World According to Garp, this senatorial New Englander still comes across as a singular blend of patrician and populist. He both tickles the narrative palate of saga- and suspense-lovers, and guides us gently down the paths of unaccustomed thought on civility, politics and art.

"I feel that the early stages of this book are very compelling to any reader," he indisputably claims. "And the reader who won't stay with me – whom I will lose when I become more technical about the craft of cooking or the craft of writing – well, to me that's an impatient reader, which is not my reader ever." Critics tend to reach for Dickens – an acknowleged inspiration, along with Melville, Hawthorne and Hardy – when trying to define the Irving touch. Anyone attuned to recent fiction of his own northern states might also put him on a blessed middle-ground between John Updike and Stephen King.

Twisted River cooked on a low, simmering light. "For the longest time the last sentence eluded me, but 20 years ago I imagined a novel about a cook and his young son who become fugitives; who have to run from some violent act that will follow them. And it was always in a kind of frontier town - a place where there was one law, and it was one man, who was single-minded and bad."

As camp chef Dominic Baciagalupo and his son Danny flee the fall-out from a fatal mistake in a roughneck backwater, rattling action yields to reflection on the choices, and the skills, that make or break a family, culture or community. The cook's son, who grows into the feted novelist "Danny Angel" via a career that teasingly follows Irving's own, at one point spars with a trust-fund hippie over a bad dog encountered on a jogging route. This miniature allegory prompts Danny to ask whether the cycle of wrongdoing and retribution can ever close. "Enough was never enough," broods Danny; "there would be no stopping the violence".

"Because of the violence that begets violence," Irving explains, "I had two other models in mind" beyond his 19th-century favourites. They were the Sophoclean tragedies of the Oedipus cycle (the cook, classicists will note, has a limp) "and what centuries from now may be the most indelible landmark of American culture: the Western movie. They have something in common with this novel: namely, when something awful and unnatural happens of a violent kind, there is almost the necessity there will be some kind of payback or retribution for that crime. The audience knows that when Oedipus kills his father and sleeps with his mother, nothing else can go right."

Irving's poetics of payback has an individual and a political face. In plot terms, the cook's reckless logger friend Ketchum – a stranger to "the world of rules and laws" - speaks for the frontier anarchism of America. He is, for Irving, "an amalgam of many people I have known: that radical libertarian whose solution to everything is, you bring the biggest gun. I love Ketchum as a character but I wouldn't necessarily want to live in a country that he ran."

In the novel's America – a nation Ketchum upbraids as "an empire in decline" - the "permanent damage" of Vietnam trickles its poison down the decades. "I think the country lost its moral footing, its moral confidence in that war," reflects Irving. As a "Kennedy father" in the early 1960s, saved from the battlefields by a "paternity deferment", Danny avoids the front – as did Irving. The difference is that Irving, trained as an officer cadet at university, did not at the time know that his first child would keep him from the carnage.

Neither did he want to stay at home. Irving attended a wedding in summer 1965 with a friend from school - the grandson of First World War general "Black Jack" Pershing - who would soon die in the conflict. "He was on his way to Vietnam, and I was on my way to Iowa with a wife and a child. And I remember saying goodbye, and envying him for leaving for Vietnam. He'd been John Kerry's roommate at Yale. And I remember actually feeling sorry for myself when I was told, well, you can't go to Vietnam: you're a father."

Kerry, the Democratic candidate defeated by George W Bush in the 2004 presidential race after a Republican smear campaign, now strikes Irving as "a hero twice over": first for his bravery in Vietnam, then for his protests against the war. "That young man in military fatigues testifying to Congress at the age of 27 was to me an exemplary model of doing the right thing."

Irving first travelled to Canada to meet exiled war resisters while researching A Prayer for Owen Meany. He still admires the cool "Canadian perspective" on his own country. His second wife, Janet Turnbull, was his Canadian publisher, and became his agent; they have a teenage son, Everett.

Now he divides his year between a remote island on Lake Huron, a Toronto apartment and a home eight miles from the ski resort of Dorset, Vermont – a town he values for its fine dining as much as for its slopes. "I don't want to mislead you into believing that I live in some godforsaken place where the only vegetable you can buy for weeks at a time is very old broccoli".

"On certain issues the Canadians are better informed on what the Americans are doing than the Americans," he says, but is irritated by "a kind of knee-jerk anti-Americanism which is prevalent" north of the border. Firm-spined New England liberal that he is, Irving takes care to stress that "almost as many people despised Bush from the beginning as voted for him. I don't want to put down my fellow-Americans without saying that half of us were right about this guy - but not quite enough."

Irving's novels steer a zigzagging course through those forests of imagination where history, myth and yarn merge. Looking for "John Irving" in his books has become for many readers a task as thrilling – and risky – as log-driving in the icy torrents of Twisted River. The son of a pilot he never knew, born in 1942, John Wallace Blunt became "John Irving" when his mother married a history teacher at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. The elite school becomes Danny's alma mater, thanks to a roundabout route via a teacher in Boston's Italian district of North End, as well as his creator's.

Irving refracts his own progress through the looking-glass of fiction. With his 2005 novel Until I Find You, this interchange became more complex than ever when he unveiled details of his biological father's family and of his sexual abuse, aged 11, at the hands of a woman a decade or so older.

With Twisted River, "I've been as faithful as I can in giving Daniel Baciagalupo my process as a writer": from the Iowa writers' workshop through college teaching in New England down to that island retreat. Danny comes under the charismatic sway of Kurt Vonnegut at Iowa, just as Irving did. "Everything that Mr Vonnegut says to Danny in this novel, he actually said to me. Word for word." Sometimes parallels veer off at playful tangents. Danny's screenwriter girlfriend wins an adapted-screenplay Oscar for an abortion-themed hit. It was Irving himself who in 2000 took the statuette for scripting The Cider House Rules.

Yet this is literature, not masked memoir. Last Night in Twisted River abounds with acidic references to media numbskulls who confuse art and autobiography, assuming "real life is more important than fiction". "Much attention is paid to those small and superficial facts which characters in a novel share with the author," says Irving.

However, equally autobiographical are "things in this novel that have never happened to me but which I fear might." Above all, "that I continue to write about losing a child". He raps the polished table. "I haven't, thank God, lost one. But, as many parents do, I think about it all the time." This motif stalks the book like a starved wolf, ready to strike.

Irving always keeps one foot in the fairy-tale forest. Fate and kinship – by blood or choice – entwine as intimately in his books as they ever did in Dickens. "Family histories", he writes, "invade our most basic instincts and inform our deepest memories". And as we sweep down the river of time, loved ones can protect against the "world of accidents" in quite unforeseen ways.

"That boy is 44 with two kids of his own," says Irving, thinking of his own eldest son. "And whenever we're fooling around and having an argument about something, I've heard him say to me many times - 'Hey, don't forget who kept you out of Vietnam!'"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments