Can journalists ever be heroes?

Journalists get a bad press in fiction – they're usually hard-faced hatchet men or bumbling fools. Is the newspaper industry really so bad? John Walsh argues that hacks make for great literary heroes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.They've been portrayed, over the decades, as fearless adventurers and talentless drudges, noble truth-tellers and wretched liars, romantic idealists and sneering cynics, profound thinkers and fatuous lightweights. In hierarchical surveys of the occupations that British people admire, they regularly appear near the bottom, just above politicians. In books, movies and TV series, they're often pictured as pushy, insensitive, malodorous, hard-drinking wretches, bullied by angry, dyspeptic bosses and concerned only with revealing the secrets of their betters. But sometimes, amazingly, they can appear as heroic, rather than foolish or unpleasant figures. Superman was one. So was Tintin. But then, so were Bridget Jones and Rita Skeeter. Yes, it's not all beer and skittles, being a journalist in the public imagination.

In television dramas, journalists are useful to the plot because – in their old-fashioned role as investigative terriers – they perform the same truth-finding function as a private eye, only with the backdrop of a thrumming newspaper-office behind them. Paul Abbott's State of Play starred John Simm as a reporter who explores the death of a female political researcher who was having an affair with an MP. It was so successful it was remade as a movie with Russell Crowe.

In movies, the newspaper hack is a useful leading man: he's not professionally tied to an office, he's reliably hard-bitten and worldly-wise, he lives on expenses and he'd do anything to get A Story – see It Happened One Night (1934), in which pissed-but-decent knight-errant Clark Gable takes runaway heiress Claudette Colbert under his wing, in return for being allowed to tell the story of her "flight to happiness"; or Roman Holiday, made 20 years later, in which growly-but-decent American hack Gregory Peck steers the woozily tranquilised virgin princess Audrey Hepburn through the Eternal City in order to get the story of her, you know, fascinating Ruritanian lifestyle.

In novels that feature journalists, by contrast, we constantly find a moral debate under way, implicitly or explicitly concerning the value of the life under scrutiny. It's very rare to find a newspaperman or woman in fiction who is not writhing with moral ambiguity. Starting from the proposition that, if someone writes for a living he or she must aspire to write the finest possible prose about the most worthwhile subjects, authors in the past have dealt with the ethical chasm that separates the out-and-out hack from the fine and subtle poet he or she could become.

The dichotomy appeared most vividly in print 120 years ago, with the publication of New Grub Street by George Gissing. Ranged against each other, in Gissing's 1891 work, are the figures of Edward Riordan and Jasper Milvain. The former is a high-minded chap determined to make his reputation as a serious novelist and refuse to compromise with the world of "commercial" fiction or newspapers (Gissing was just the same). The latter is a shameless, money-grabbing opportunist, who knocks off articles as though on a production line. "Your successful man of letters is your skilful tradesman," he tells his sisters. "He thinks first and foremost of the markets; when one kind of goods begins to go off slackly, he is ready with something new and appetising." It's a battle of the hack versus the heavyweight. When Reardon, on the brink of financial ruin, tries his hand at a schlockly novel, he is too "good" to make it work, his fortunes dwindle further and his wife Amy leaves him. Milvain gets a job on The Current and marries Amy. In the struggle between Art and Hackery the latter triumphs, to loud boos from the reader.

A direct descendant of Milvain is "Books" Bagshaw in Books Do Furnish a Room, the 10th book in Anthony Powell's 12-volume roman-fleuve, A Dance to the Music of Time. Bagshaw is the apotheosis of the hack journalist, omni-competent in mediocrity of all kinds: "He possessed that opportune facility for turning out several thousand words on any subject whatever at the shortest possible notice: politics; sport; books; finance; science; art; fashion – as he himself said, 'War, Famine, Pestilence or Death on a Pale Horse.' All were equal when it came to Bagshaw's typewriter. He could take on anything, and – to be fair – what he produced, even off the cuff, was no worse than was to be read most of the time. You never wondered how on earth the stuff had ever managed to be printed."

Here we see Powell expressing his Gissing-like distaste for the kind of writing that comes too easily. Without mental struggle, and time set aside for mature reflection, he implies, writing can't be any good. The good stuff should be left to the novelists. Journalists are just too damn free (or rather "facile") with words.

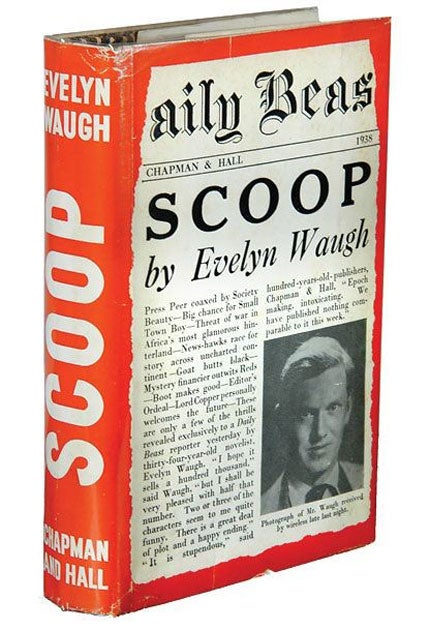

In Scoop by Evelyn Waugh, a different perspective prevails between two characters. The difference here is not between the idealist and the churner-out of words; it's between the innocent chump and the worldly sophisticate. Both men are, unfortunately, called Boot.

John Boot is a smart, well-connected young novelist who "between novels...kept his name sweet in intellectual circles with unprofitable but modish works on history and travel", and wants to leave London and head for a war zone to escape a troublesome girlfriend. Strings are pulled for him by a society friend who knows Lord Copper, awesomely grand proprietor of The Daily Beast. But when his lordship summons Boot, the wrong one is sent to the war.

William Boot, a gentle, herbivorous country-dweller, contributes to the Beast a weekly column of nature notes called "Lush Places" ("Feather-footed through the plashy fens passes the questing vole."). He is sent to Ishmaelia, where civil war is about to break out. After uncomfortable encounters with Fleet Street's professional war correspondents, the hopeless Boot finds himself embroiled with a dictator and an attractive blonde, files 2,000 words fuelled by "Love, patriotism, zeal for justice and personal spite," and becomes a hero. Back in England, he is feted – but John Boot, his glamorous namesake, takes credit for the story, and William subsides back into the country habitat he so grudgingly left.

Waugh was, of course, satirising the iniquities of journalists – their venality and love of expenses, their lack of emotional or moral commitment – while showing that, basically, any good-hearted twit could do the job of foreign correspondent for a national newspaper.

Scoop was published in 1938. Two years later, Alfred Hitchcock's Foreign Correspondent was released. In it, Johnny Johnson, a dim but good-hearted crime reporter from the New York Globe is sent to Europe to report on its imminent drift to war. His utter lack of knowledge or insight into international politics is considered a bonus ("What Europe needs is a fresh, unused mind," grates the editor.) In London, Johnson encounters the Globe's actual foreign stringer, Stebbins – played by the comic writer Robert Benchley – a bleary drunkard who does nothing but pass on government handouts, signing them "Our London Correspondent".

Clueless amateur takes over from alcoholic know-nothing – it's not a great advertisement for the modern newsman, is it? But it all comes good in the end when Johnson contrives to speak via radio link to the US public, alerting them of America's need to enter the war.

Gifted innocents and lucky amateurs make journalistic heroes, then – but what about those who deal in the less elevated sections of the newspaper world? In Scoop, a plangent note is struck by Mr Salter the Beast's foreign editor. He never, it seems, really wanted the job: "As he drove sadly out to Lord Copper's mansion he thought sadly of those carefree days when he had edited the Woman's Page, or, better still, when he had chosen the jokes for one of Lord Copper's comic weeklies. Mr Salter's ultimate ambition was to take charge of the Competitions."

In 1967, Michael Frayn published a novel specifically about the backroom hacks of a newspaper – the people responsible for the "Thought for the Day" slot, the crossword, the "In Years Gone By" nostalgia corner, the Nature Notes. Apparently drawing on his experience at The Guardian, Frayn showed his journalists to be frustrated whingers, stuck in a professional backwater, longing to escape from the dusty office and enter the sparkling sunlit uplands of TV broadcasting.

More recent novels have given us images of journalists who occupy certain niches – seldom to their credit. In The Bonfire of the Vanities (1987) Tom Wolfe created the charming Peter Fallow, a washed-up, alcoholic, plagiarising, British hack on the City Light tabloid, who is given a chance of redemption when he's asked to write about the black victim of Sherman McCoy's hit-and-run accident. Amanda Craig in A Vicious Circle (1997) revealed the world of literary journalism and book reviewing to be a seething snake-pit of corruption. A well-known literary editor protested that a fictional editor was too close to him for comfort, while the character of Ivo Sponge, the louche, skirt-chasing party animal, was rumoured to be based on several entirely blameless figures. In A Week in December (2009,) Sebastian Faulks introduced the world to R Tranter, another literary journalist and book reviewer who delights in trashing the productions, and ruining the reputations, of writers who are doing rather better than himself.

Which brings us almost up to date. "I do not think that there will again be a major novel, flattering or unflattering, in which a reporter is the protagonist," wrote Christopher Hitchens in 2005. "Or if there is, he or she will be a blogger or some other species of cyber-artist, working from home and conjuring the big story from the vastness of electronic space." As though to prove him wrong, Annalena McAfee's debut fiction, The Spoiler, out next month, seizes the noble tradition of the Journalism Novel and rings some delightful changes on it.

The Spoiler sets two journalists on a collision course in 1997, at the end of the Major government and just before the New Labour landslide. Honor Tait is an 80-year-old veteran foreign reporter whose career overlapped with many of the 20th century's most momentous occurrences and most interesting people. Her first pieces of journalism, later collected in Truth, Typewriter and Toothbrush, were reports from the Spanish Civil War, the Normandy landings, the liberation of Buchenwald, a Korean foxhole. She can look back at her friendships with Picasso and Cocteau, her flirtation with Hollywood royalty (her third husband was a film director), her meetings with Charles De Gaulle, Samuel Beckett, General MacArthur, Madame Chiang Kai-shek... Clearly meant to suggest a tough-bunny hybrid of the Daily Mail's veteran foreign correspondent Anne Leslie and the glamorous photojournalist Lee Miller, Tait is now a fretful, querulous old lady, worried about losing her faculties and joining the great back bench in the sky.

Into her life, to interview her for The Monitor's glossy intellectual Sunday magazine, comes Tamara Sim, 28, a freelance sub-editor and occasional writer for Psst!, the Monitor's down-market Saturday gossip rag. Tamara is several light years apart from Honor, in every conceivable respect. She is ignorant of history, literature, art, culture and thought. Her métier is the two-paragraph squib about celebrity misbehaviour, the agent-provocateur sting, the ring-round survey, the vox-pop inquiries ("Me and My Chair – Furnishing Secrets of the Rich and Famous"), the "10 Best Celebrity Bad Hair Days" feature – all the paraphernalia of small fillers and five-things-you-ought-to-know boxes which routinely dot the pages even of serious newspapers. The limit of her ambitions to be given a "pugnacious, pun-packed Tamara Sim Column" – and her interest in Tait's boring, old-fashioned and incomprehensible journalism is nil. All she wants is some stuff from her about her love life, celebrity shags, famous names...

McAfee, who edited the Guardian's Saturday Review for six years, gives us a rare sighting in literary history – a journalist whom we're meant to admire. She also has hilarious sport with the callow foolishness of Tamara, who's in a direct evolutionary line from Jasper Milvain to Bridget Jones. The girl prodigy of Monitor isn't seen as evil or stupid – on the contrary, she's shown as hard-working and enterprising – but we're encouraged to laugh at her lack of any hinterland, any intellectual curiosity, any interest in the past, any understanding that journalism might be about something more than gossip and emotional disclosure.

But Ms McAfee isn't content to leave Honor and Tamara as two warring archetypes, one honourable, the other contemptible. Her novel asks: is the distinction between them as simple as that? Are we to assume that the octogenarian Honor is 100 per cent shining beacon of truth and fine reportage, and that young Tamara is 100 per cent worthless ditz? Honor worries that "her entire life – even her work – had seemed a sequence of Lilliputian diversions, futile displacement activities... all the incessant busyness, to weave this cobweb in a dusty corner." And as Tamara fails to find anything worth writing about in Honor's crotchety remembrances, the more enterprisingly journalistic she becomes.

One hundred and twenty years after Reardon and Milvain exemplified two extremes of writerly endeavour in New Grub Street (and yes, their names have been pinched by Radio 4's Ed Reardon Show,) journalism is still being used in fiction as the basis for a moral debate about the value of a life. Seventy years after Scoop, we've learnt not to laugh at the foreign correspondent, who is a witness to history – but we haven't quite given up ridiculing the "Books" Bagshaw figure, with his fatal facility for turning out copy on any subject, to any deadline. The Spoiler shows that there's a lot of yelping life in the hacks-on-the-make genre – even as journalist readers guiltily wonder if (gulp) there's slightly more of Tamara in them than there is of Honor.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments