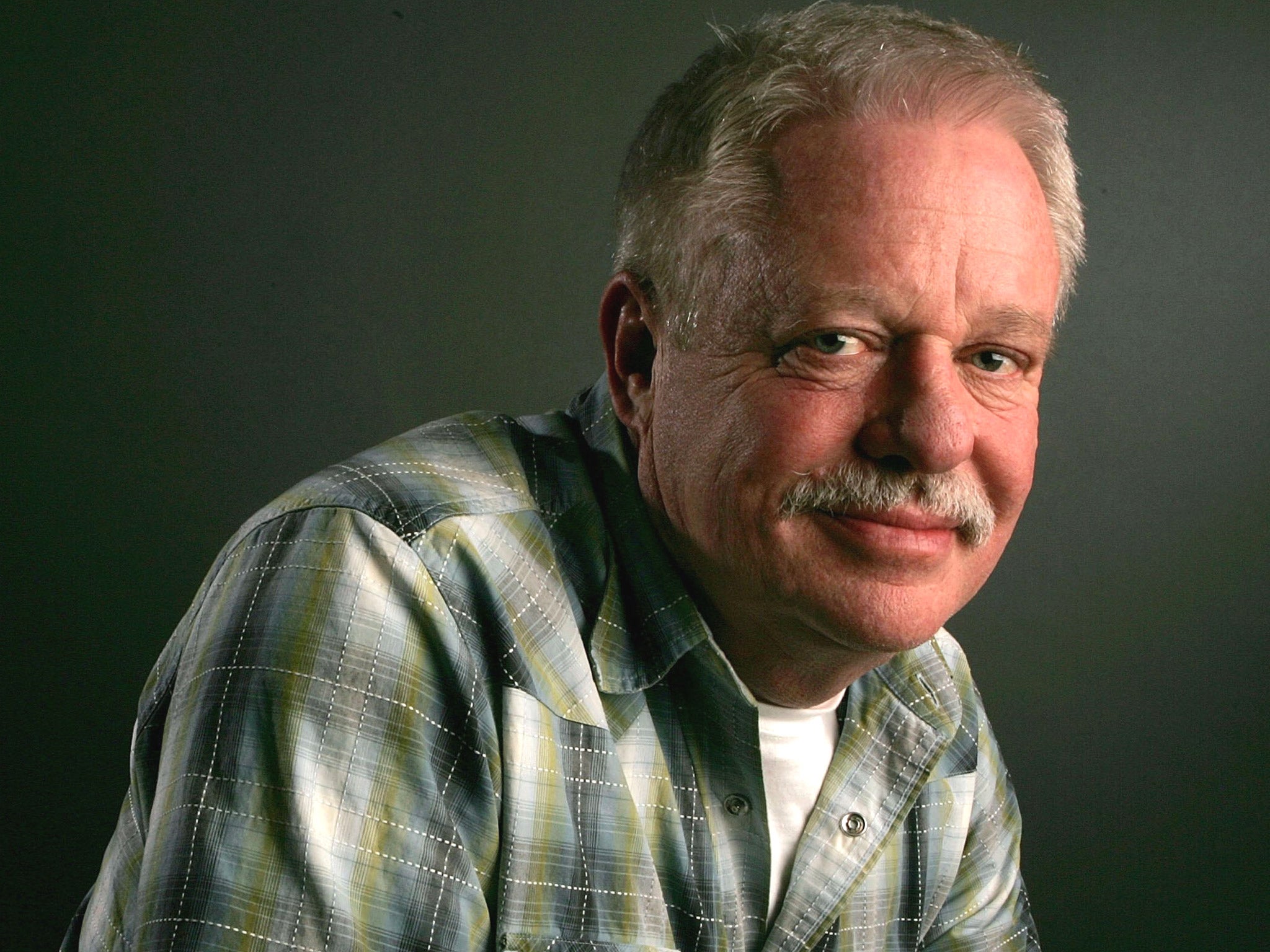

California dreaming: Armistead Maupin's 'Tales of the City'

The series of novels have changed the lives of countless gay people. As the last volume is published, Patrick Strudwick pays a personal tribute

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Living above a strip joint is significantly less salubrious than you might expect. Cockroaches scuttled along the skirting boards, lit up by the pink glow of the neon outside. Downstairs, heels clickety-clicked against poles, a never-ending tapping through the floorboards.

A pimp raged in the room next door, two brothers on the other side pulled a gun when asked for rent, and the police would raid at dawn – not keen, apparently, on the mafia who ran the building. The carpet was mouldy. The shared bathroom had a bin for used toilet paper. It was summer, it stank; the roaches loved living here and so did I. Because this – this – was San Francisco, the mecca for sexual misfits.

I hadn't run away (only the stupid or desperate run away): I was on a pilgrimage. Five thousand miles from home, aged 21, I had reached my Holy Land. Pilgrimage had beckoned five years earlier, in 1993. Channel 4 had broadcast an adaptation of the first in a series of novels that would change the lives of gay people for ever: Tales of the City. Set in the late Seventies, with characters from across the sexual spectrum, free-loving and cannabis-inhaling in the most epically beautiful of cities? For a 16-year-old in dreary old Guildford, it looked like the world's greatest acid trip: Bacchanalia-on-Sea. But it wasn't the last days of Rome that I was searching for: it was a home free of suburban suffocation, gender expectations, fear, boundaries. Somewhere I had a hope of happiness.

Tales of the City brought me to California, but in bringing the first positive portrayals of gay, bisexual and transsexual lives to mainstream audiences, it fired a revolution.

The books began as a column in a local newspaper, The Pacific Sun, in 1974, before moving to the San Francisco Chronicle. After the 1960s hippie explosion in the city's Haight-Ashbury neighbourhood, counter culture was flourishing in a halo of patchouli oil and poppers, and a young writer called Armistead Maupin wanted to capture the zeitgeist in Dickens-form serial fiction. It wasn't always easy. His editor had a chart up in his office with two lists: the straight and non-straight characters. (We've always been on a list somewhere.) If the latter became longer than the former, it would alienate readers, his boss thought. Instead, those of every persuasion began to savour the columns, persuading Maupin to compile them into a longer form. The novels, which have now sold more than six million copies globally, came to depict the most pivotal period in gay history: the disco-balled hedonism of the Seventies, the Aids-ravaged hell of the Eighties.

Maupin's central protagonist was Mary Ann Singleton, a 20-something secretary straight off the bus from Cleveland, Ohio (another planet): "green" but plucky, square but also desperate to "bite into that lotus" as her new Tennyson-channelling landlady Mrs Madrigal observed.

Anna Madrigal, the matriarch, ran a divided-up house at 28 Barbary Lane, in the city's bohemian Russian Hill (just about visible from my Scorsese-esque abode) where the novels' main characters lived together: a commune of sorts, a home for outsiders. She was all shawls and spliffs, mystery and wisdom and wondrous pathos; bookish, bossy, a rack of lamb in the oven as she chatted to her beloved plants. She was born a boy.

The central gay character was Michael "Mouse" Tulliver. He wanted love, marriage – ideally an English professor with elbow patches and a big dick, but a kind heart would suffice. He longed to reach the "furniture- buying stage". Huge-hearted, oft-disappointed, insecure, eager – no character in literature would more gay men relate to. He was us. And he was Maupin. He looked for love in all the (forgive me) schlong places: bathhouses and bars, but eventually it paid off.

When he wrote to his Floridian parents to tell them he was gay, he provided not only a much-needed catharsis for anyone who'd come out, but a prime template for those contemplating it: "I wish someone older than me and wiser than the people in Orlando had taken me aside and said: 'You're all right, kid. You're not crazy or sick or evil... you can love and be loved, without hating yourself for it'... I'm the same Michael you've always known. You just know me better now. Please don't feel you have to answer this right away. It's enough for me to know that I no longer have to lie to the people who taught me to value the truth."

Tales's vanguard position in 20th century culture can be told through its invasion into virgin territories: literature's first trans-gender character; the first character to die of Aids; but, gliding above these is its four-decade theme – the first depiction of happy gay life; of a blissful domestic set-up. Home – and family – for homosexuals. But this was a new family, the "logical" rather than biological family: one we choose. Before Tales, every story of sexual renegades was tragic: the outcast; the disgraced; the imprisoned. It was Oscar Wilde's demise and Radclyffe Hall's The Well of Loneliness. It was a seedy existence of lies and scandal and toilets; a "waste".

Maupin subverted everything. In Tales, we – the non-straights – were no longer the bit parts, but the equal parts. Tales felt utopian: Nirvana with hash cakes. But it was more complex than that, not least in its roll-call of minor characters. Men dressed as nuns flying past on roller skates, drag queens sniffing poppers in church, whacked out hippies, jumped-up closet cases, cult members, psychics, a paedophile, a white model posing as black and an heiress impregnated by the delivery man as her husband gobbled in a steam room. These were Quaalude-swallowing, coke-sniffing, joint-toking reprobates. Glorious or hideous, they were hyper vivid, all.

And all set against the magic of San Francisco: the rotating light from Alcatraz, the fog rolling off the bay, the ding-ding of cable cars. Readers could smell the liberation. Our life – love and sex, hedonism and domesticity – was all there: a kaleidoscopic panorama brimming over the Pacific. Tales became a bible; a gay gospel. Before the procession of Nineties and Noughties role models, before validation or rights, Maupin painted what could be – beyond this peninsula. With each stroke of the space bar, he gave space to possibility.

For all the external changes unleashed through protest, Tales heralded the great internal one: a belief that we were just as good, just as worthy, the knowledge that we could be fulfilled. In the end, his pen proved as mighty as our placards.

"It was truly groundbreaking, a pioneering antidote to the usual portrayal of gay people as victims, problems and threats," says Peter Tatchell, the gay rights campaigner, who I spoke to this week. "Together with the gay liberation movement, Tales helped transform gay consciousness, making people feel better; more confident and self-accepting."

After a gap of 20 years, Maupin returned to the series in 2007, with Michael Tulliver Lives, then in 2011 with Mary Ann in Autumn. Tomorrow, with the release of the ninth book, it is the turn of Mrs Madrigal. Though now a nonagenarian in decline, she glimmers resplendent as the sage, spirited embodiment of the cultural changes of the past 40 years. For fans, The Days of Anna Madrigal offers yet more poignancy: it is the final instalment. But how did it feel for Maupin to write the last chapter?

"It is bittersweet, but there is also enormous relief, because I feel like I've landed the plane on the aircraft carrier," he says on the phone from Santa Fe, where he now lives with his husband. "I feel satisfied with it. As soon as I delivered the manuscript, we planted a commemorative tree – a honey locust down the end of the garden, that we named 'Anna's tree'."

The book series occupies a profound place in the lives of its devotees. Can he begin to conceive of the impact it's had? "That's the challenge," he says, the twang of his North Carolina upbringing still audible. "A lot of people cry when they wait in line for my autograph. Because the story has been going on for 40 years, it tends to intersect with people's lives in ways I can't even begin to imagine. A woman told me her brother was buried with my books. What do you say to that except feel it and appreciate it? Every person I meet tells me a different story, but a lot of it has to do with coming to terms with who they are."

In the beginning, he says, he just wanted to tell stories, but the politics of what he was describing soon surfaced. So how much is Maupin a writer and how much an activist?

"Both are thrilling to me. I love being a storyteller. At the same time, I think the most important thing I've done is allow people who have heretofore been oppressed and silent to be joyful and open. And I think there's a certain amount of queer chauvinism in Tales.

"I think many gay people, if they do it right, end up as superior human beings because they've gone through this experience of having to keep their mouths shut. They've learned to view all of humanity in such a way as to be more compassionate than the average straight person who was raised knowing that they are acceptable in the eyes of the church, the government and their families. Those of us who've had to make our own way have become stronger and kinder. If you're lucky."

Since the outset of the gay liberation movement in 1969, coming out has been one of its central tenets – a belief shared by Maupin. "The underlying message of Tales is: 'Get out there: live your life and live it openly'," says the author, now 69. "It seemed to me from the very beginning that we [LGBT people] had to make ourselves known to the world before we could ever get out of this prison."

Maupin helped unlock the gates. His world, which was simply a better-written, more complex and thus truer account of the new reality of LGBT lives, prevailed. It would prevail on our small screens, in Queer as Folk, Will & Grace, The L Word and Six Feet Under.

It prevailed elsewhere in literature: Damian Barr's acclaimed memoir Maggie and Me; Patrick Gale's Rough Music; Alan Hollinghurt's The Swimming Pool Library and The Line of Beauty – all may never have reached such broad audiences without Maupin having proved the crossover appeal of multi-sexual storytelling. The Line of Beauty, which won the 2004 Booker Prize, sold more than 100,000 copies.

Our theatres, emboldened, reaped the benefits, too: Another Country, Shopping and Fucking, Angels in America, Plague Over England, Beautiful Thing. Jonathan Harvey read the Tales novels in 1990 before writing the last of these. "They seemed to describe my life," he tells me. "Armistead's warm heart beats through every line. If I've taken anything from his work it's this: write about the world you know."

The world we knew became known. Finally, we had grasped our own narrative. The tragic homosexual wasn't so much gone as lost in a crowd.

All of which meant that when The Days of Anna Madrigal thumped on my doormat in London last week, I tore it open and stared, unready for conclusion, poised for a grief-soaked finale. When I eventually began reading, a few days later, it held me as the others in the series always had, like a hammock: rocking, blissful – the precise language, delicious interwoven storytelling and now archetype characters engulfing in Technicolor 'til the very last word.

Tales didn't merely call me to San Francisco for a few months in the dewy glow of youth. It didn't just persuade me to take a job at a coffee bar there because someone said that Armistead Maupin was a regular customer. It forever reminded me – and millions more – of the richness and humanity of trans, bi and gay people, the ordinary and extraordinariness of us all.

The books helped my generation – and the one before – realise itself. And they helped me become myself. Returning to London, I decided to abandon my training as a classical composer to become a journalist. What could be more powerful than telling people's stories?

But while I found the home I was looking for back in Britain, I never quite recaptured the joy of looking out from that mouldy old room, Maupin's glistening world winking back at me. µ

The Days of Anna Madrigal (Doubleday, £18) is published on Thursday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments