Boyd Tonkin: Behind the hype and glamour, African writers still share Achebe's vision

The Week in Books

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1987, Chinua Achebe returned to the novel after a long gap with Anthills of the Savannah. The forefather of today's "boom" in Nigerian - and other African - fiction matched his scorching critique of corrupted power with a fervent affirmation of the writer's duty to defy it: "it is the story that outlives the sound of war-drums".

Achebe, who died last week at 82, heard many kinds of war-drum in his time - most notably, as a risk-taking supporter of the late-Sixties Biafran breakaway that saw his own Igbo people rebel against Nigeria's federal state. His stories will outlive them all.

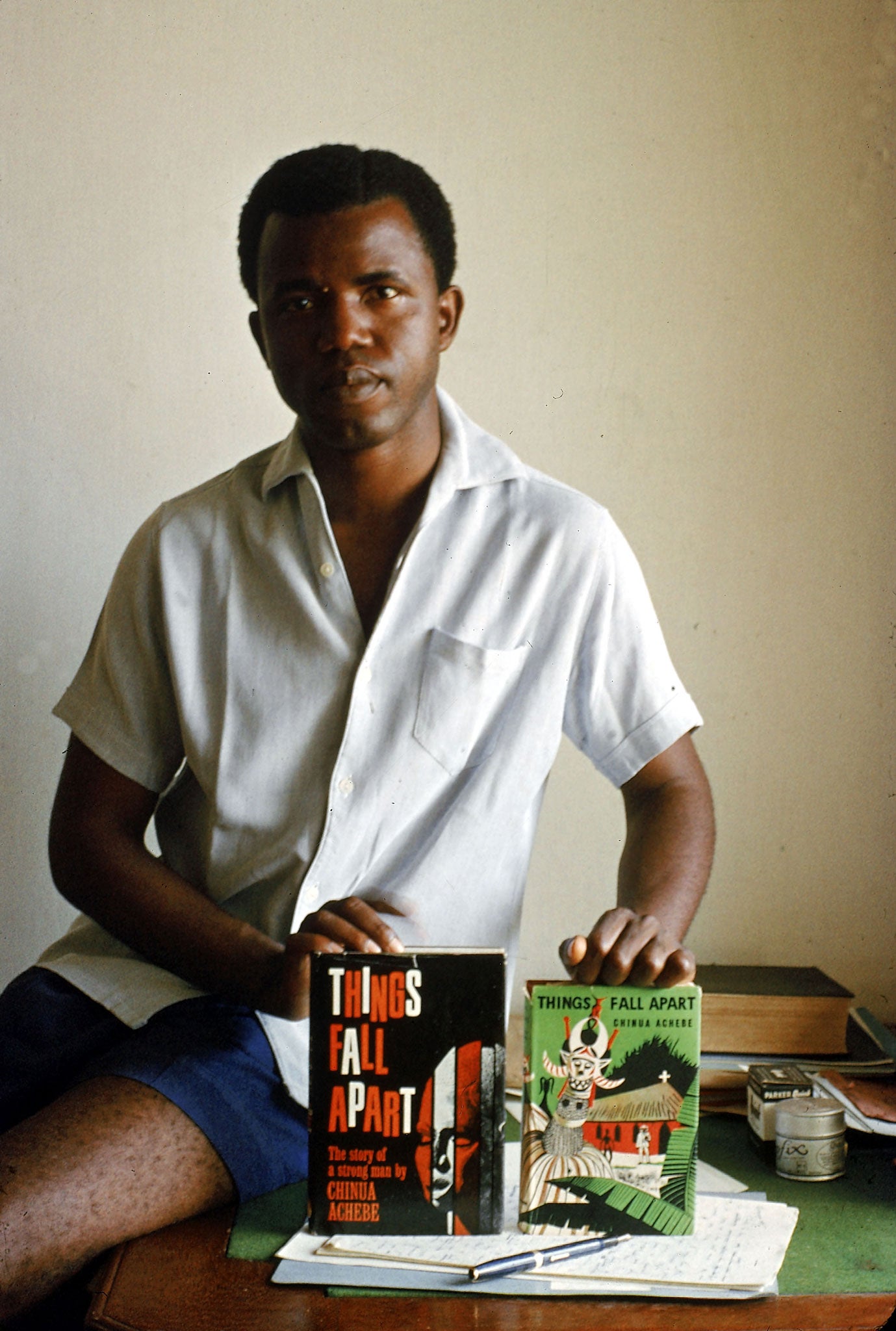

Rich in honour and acclaim, the author (55 years ago now) of Things Fall Apart departed with the fiction of Africa and its global diaspora in seemingly rude health. This week alone sees the publication of Taiye Selasi's stellar debut and a further advance in the scope and sweep of Aminatta Forna's work.

Next month, the bestselling Chimamanda Adichie - who often pays tribute to Achebe as model and mentor - releases Americanah. Nigerian authors in particular are now the target of a frantic prospectors' rush. In a bizarre re-run of colonial-era plunder, publishers and agents swoop with predatory relish on fledgling talents likely to flourish in the international marketplace.

It goes without saying that booms will always end in bust. Equally, their din and smoke hide much of the actual landscape. Look beneath the sparkly surface of hype, and the monsters that Achebe wrestled still stalk African literature. Just last month, during the illuminating offshoot of the Etonnants Voyageurs festival that Congo-born writer Alain Mabanckou and his colleagues organised in Brazzaville, I came across plenty of examples of the unfinished business that makes Achebe's work texts for life rather than just for study.

In the opening ceremony, a brave young woman interrupted the Republic of Congo's Minister of Culture to condemn poverty and homelessness in a potentially wealthy land: a pure Achebe moment. Under the trees outside the Palais des Congrès, Teju Cole - subtle and eloquent, a Nigerian American prodigy - spoke of his visits, not that long ago, to a Lagos bookshop. Tucked away, far apart from the sections devoted to "Literature", he found a few dusty shelves of "African Literature". Such crippling assumptions - within the continent as much as outside it - gave Achebe his mission. As Cole said: "Decolonising the mind is an unfinished process. It's something you have to keep doing every day."

Elsewhere, I heard the young writer Fiston Mwanza - from across the river in the Democratic Republic of Congo - talk of his breadline childhood. Both his parents worked late. He faced long post-school hours of waiting for a meal. "You must read," said a friend. "Reading is the best way to kill hunger." He did, voraciously.

Also from DRC, the captivating novelist In Koli Jean Bofane (author of the prize-winning Mathematiques congolaises) recalled the Belgian colonial prohibition of education to Africans except trainee priests, and then the stifling effects of Mobutu's dictatorship. So now a "good rage" of long-thwarted passion fires his nation's writers.

Over dinner, at a riverside restaurant, Bofane pointed out a neon-lit tower-block in Kinshasa on the Congo's other bank. He told of how, with a little elementary chemistry and a truck-load of cheek, he and a friend built up a liquid-soap business in offices there (and took over the management of the building). "In the Occident, people have it easy," he mused, with no rancour. "They don't have to fight."

Africa's many fights persist. Behind the glamorous cover-stars of its new literature (good luck to them; they have the talent as well as the charisma), Achebe's landscapes of conflict endure. Read him not as an ancestor, still less as an idol, but as a contemporary.

PLR: London seizes an asset from the north

Ministers and civil servants always talk about the need to disperse a London-heavy state and run official bodies from (say) Stockton-on-Tees rather than Bloomsbury. Until they need to save cash. From October, the Public Lending Right scheme that makes payments to authors for library loans, now based in Stockton and directed by the estimable Jim Parker, will form part of the British Library bureaucracy. The office stays up north but, to save £750,000 over 10 years, control shifts to WC1. So much for decentralisation.

E-books wreck the numbers game

Until recently, one could track the overall health of the book economy by charting the annual changes in the output of titles. It was an inexact science, but the raw figures acted as a crude thermometer. No longer: as with so many aspects of the industry, digital publishing has transformed - and confused - the numbers game. The statistics for 2012 show an astronomical total of 170, 267 titles published in the UK (with 57,999 of those e-books).

Even that staggering sum represents a fall from 189,979 in 2011 - after the e-publishing boom really began to swell the accounts. Frankly, these figures now mean next to nothing. Thanks to digital platforms, the institutional bars that controlled access to "publication" have permanently dropped. For sure, this revolution deserves a cultural democrat's two cheers. But it busts that old thermometer beyond repair.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments