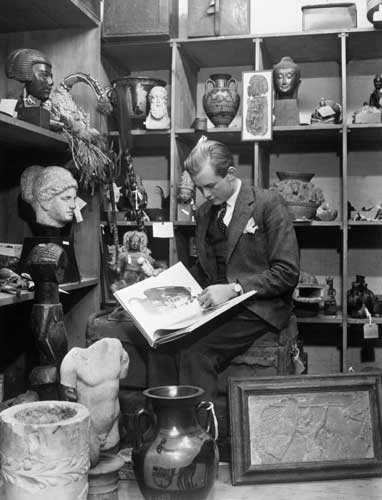

Boy wonder: A revealing view of Bruce Chatwin's early years at Sotheby's

Long before he became a celebrated traveller, novelist and controversialist, Bruce Chatwin was a 'Sotherboy' – a precocious young art expert for the famous auction house. Fifty years later, his colleagues recall Chatwin's Bond Street days with affection

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

On a crisp winter morning 50 years ago Bruce Chatwin stepped off New Bond Street and into the galleries of Sotheby's for the first time. He was an 18-year-old, dough-faced boy straight from Marlborough College. The following eight years spent at the auction house were to prove pivotal. They would inform his unique prose style, introduce key themes to his work, provide him with a wife and create a lasting fascination with the allure of objects.

The world into which Chatwin entered that morning was experiencing a dramatic change. That season the art market had shifted up a gear, much as it did in September this year when Sotheby's hosted the groundbreaking Damien Hirst auction. In October 1958, the company staged the first black-tie evening auction of Impressionist paintings ever held in London. The Goldschmidt sale changed forever the way in which art was marketed, auctioned and desired by a new global audience. Bond Street was awash with reporters, their bulbs flashing on a dizzying array of dinner-jacketed bidders.

Philip Hook, Sotheby's current Senior Specialist in Impressionist & Modern Art, describes the importance of the event in his forthcoming book The Ultimate Trophy, published in January by Prestel. "The auction house went from a world of dusty old hamsters, just pursuing their subjects, and propelled it into the world of really big business, when suddenly Greek millionaires and Hollywood stars were competing for Impressionist pictures."

Stars there certainly were. Margot Fonteyn, Anthony Quinn and Kirk Douglas sat cheek by jowl with competing dealers. In 21 minutes a new world record for a fine art sale was achieved. "Like a Covent Garden great occasion," judged the Western Mail correspondent.

Chatwin's introduction to the art world was more sedate. He was sent to tag property coming up for sale, under the charge of the Works of Art numbering porter Marcus Linell. "For two years I put lot tags on works of one sort or another and Bruce came to help me, at which he was simply hopeless," recalls Linell. "He wasn't good at things that essentially bored him. Lotting up is a fairly tedious thing; it has to be done right and it has to be on time. There were lots of things that were much more amusing as far as he was concerned: wandering the galleries, coffee-housing."

However, Linell bonded with his new colleague. "He was a delightful, agreeable human being. When he joined he was living in St John's Wood and I lived there too. We'd go back and forth quite a bit so we had a lot of time to talk." Eventually, though, the tardiness grew problematic and Linell had to "get rid of him".

Chatwin was moved to the Furniture Department where he "mixed like oil and water". Then came the turning point. He caught the attention of the chairman, Peter Wilson. The facts are, like much in Chatwin's life, frosted with misdirection and self-promotion. Did he spot a fake Picasso? Did he dazzle with his translation of an inscription on a Greek amphora? Who knows. "Doing a Bruce" in the company's Mayfair rooms meant parcelling up a story with the most flamboyant detail possible. Whatever the cause for his rise, no one could deny that Chatwin had "a terrific eye for objects", as Linell puts it, and a ravenous hunger for arcane information. In Tearing Haste: Letters between Deborah Devonshire and Patrick Leigh Fermor (John Murray £25) has Leigh Fermor summing up the brilliance of his autodidact friend: "We've got a fellow-writer called Bruce Chatwin staying," he writes to "Darling Debo". "V nice, tremendous know-all, reminds me of a couplet by O Goldsmith: 'And still they gazed and still the wonder grew, / That one small head could carry all he knew'."

Peter Wilson was to have an extraordinary influence on Chatwin. The chairman had masterminded the company's gold rush years and, post Goldschmidt, expanded the market for Impressionist paintings. Philip Hook points out that this "was the first time people bought art because it was new. Our age equates novelty with quality in art but then that was an incredibly unusual idea." Under Wilson's tutelage, Bruce was to become the first dedicated cataloguer of the field in Sotheby's history.

Linell remembers Wilson as a "completely brilliant" but ambiguous character who perfectly suited the deep-freeze days of the cold war. There was a persistent rumour that he was the fifth man to Burgess, Blunt, Philby and Maclean. He was, Linell states, "undoubtedly the most extraordinary person who's ever been at Sotheby's". He was as tricky and secretive as his protégé and married to the company. When Chatwin courted, and later wedded, Wilson's secretary, it utterly baffled his boss.

Chatwin was to benefit from Wilson's hot-housing of talent during the boom time. He became the archetypal "Sotherboy". However, he could still be reined in, as he discovered a couple of years later when Michel Strauss turned up to co-run the department. "My impression on arriving that first morning was that he wasn't at all happy to see me there," says Strauss. "The first sale that came in after I arrived was the Somerset Maugham sale and we agreed to catalogue it together in the morning. When I got in at 9.30, I found he'd been in since 5.30 or 6am and catalogued the whole thing. That's when I realised it had become very competitive. But that competitiveness became our single-most benefit in a way. We were both trying to do our best. We complemented one another very well." Chatwin smartened up his act. The school-leaver suits gave way to slate-grey tailored threads and as his appearance sharpened, so too did his ambitions.

Neither Linell or Strauss were aware at the time that Chatwin had literary aspirations. Strauss recognises in retrospect that the firm was the starting point to "a gradual process". Years later, "when his articles started appearing in the Sunday Times it was quite a surprise, but a nice surprise."

Chatwin's case is far rom unique. Sotheby's has consistently fostered the talents of fledgling writers. Definitive studies of artists, movements and the great collections have sprung from talents within its doors. As have novels. Richard Aronowitz Mercer, Head of Restitution, recently drew on his day job for his art-loot driven drama Five Amber Beads. In addition to his social study of the Impressionist market, Philip Hook has also penned five thrillers played out among galleries, museums and dealers' haunts. "I think it's the most wonderful place for a writer to work," says Hook. "There is such a variety of character. One encounters so many different people all driven by something quite passionate. Things have changed since Chatwin's day, when people were purer collectors, simply because works of art have become so much more valuable. The money side of it becomes a much bigger part than it did 50 years ago. And to a writer the money adds an extra excitement."

If the job provided material and characters to which Chatwin would return time and time again, it also provided new ways of writing. "Cataloguing vocabulary has a language of its own which I find wonderfully archaic but still has a definite meaning," states Hook. "Terms like staffage, meaning the people in a landscape, and I love the phrase 'a wooded landscape with a dog favouring a tree stump'." Chatwin's entries in the auction catalogue of the William Somerset Maugham Collection are a tiny fraction of the length now afforded to great paintings. Yet even in the spare, skeletal structure he worked within his flair for uncovering drama can still be found. They appear like Rolleiflex snapshots of artistic intrigue (the Renoir "found in the studio at the death of the artist", the history of a Tahitian Gauguin painted on a shack door and discovered by Maugham while researching The Moon and Sixpence).

He further developed his trim style for his first published piece of writing, "The Bust of Sekhmet", which appeared in 1966 among the pages of The Ivory Hammer, Sotheby's journal. Three years previously the annual had played host to James Bond. In "Property of a Lady", a story Strauss specially commissioned from Ian Fleming, 007 takes to the auction room with the same gusto he devours a martini: "Bond turned to his catalogue. There it was, in heavy type and prose as stickily luscious as a butterscotch sundae: The Terrestrial Globe, designed in 1917 by Carl Fabergé." Naturally, the underbidder is a top Soviet agent.

Chatwin's article was less racy, an investigation of the myths and dramas attached to the bust of the Egyptian Goddess of War and Strife which guards the front entrance of Sotheby's offices. In it Chatwin delivers his sentences like a skimming stone, touching on a fact, zipping on to the next reference before shooting off to another touch point, leaving a pool of everyday detail untouched. This mirrors the way cataloguing flits from provenance to literature citation to exhibition tally. It demands a certain level of knowledge and understanding from the reader.

Chatwin's volatility during his time in the "Imps" could be trying, yet Strauss is emphatic that his charisma was invaluable to the department. "He could be extremely charming, and he used that to get things he wanted." When Wilson sent him off to the Dorchester to butter up a cantankerous Somerset Maugham, Maugham threatened to cancel the sale, and Chatwin countered by allowing the octogenarian to play with his hair (freshly shampooed on Wilson's direction). Although Chatwin made much of this outrage, it was, many believe, just another example of "Bruce re-writing history".

Chatwin left Sotheby's in 1966 having become one of the company's youngest directors. Over two decades after his departure he would return to the world of the obsessive collector for his final tour de force, Utz. Written as Chatwin was dying, this short tale of a man finding an escape from a shadowy Soviet-era Prague through his hoard of Meissen figurines remains a pristine miniature. The character of Utz was based on the Czech scholar Rudolf Just who was introduced to the writer by Kate Foster, Sotheby's porcelain specialist. (Serendipitously Just's collection was successfully sold through the house in 2001.)

In a letter to Chatwin's biographer, Nicholas Shakespeare, Dirk Bogarde declared the book as "spare as a grocer's bill". He was sympathetic to Chatwin's fox-holed personality. Both men were adept at reinventing themselves and skilled at keeping their private lives closeted. So when the actor was asked to nominate his book of the year in 1989, he chose What Am I Doing Here (Chatwin's posthumous collection of journalism). In an apt echo to Chatwin's Bond Street days, Bogarde praised it for the "detailed pictures which it set before my eyes".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments