Books of the month: From Long Island by Colm Tóibín to The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley

Martin Chilton reviews the biggest books for May

Tiffany Murray’s mum Joan, who was the chef at the famous Rockfield recording studios in Wales, cooked for some of the biggest music stars of the 1970s. There were no life-on-Mars bars for David Bowie, though, who was very frugal. “David Bowie hardly ate. If you asked him, he’d say, ‘a little bit, please’. Very polite. He drank milk. Always smoking,” Joan recalled.

Snapshot memories of other famous musicians who used the studios – including Dave Edmunds, Rush, Hawkwind – fill Murray’s delightful childhood memoir My Family and Other Rock Stars. It’s full of anecdotes to make you smile. My favourites were Freddie Mercury and his Queen bandmates playing rounders in the quadrant, Simple Minds (appropriately named) having food fights, and Lemmy, away from his Hells Angels pals, wanting the crusts cut off his bacon sandwiches.

The word “miserable” appears 30 times in The Diaries of Franz Kafka (Penguin Classics) and although it’s hardly a surprise that the Prague-born author of The Trial was woebegone, it is a comfort that he kept some of his maudlin entries succinct. The diaries cover 1909 to 1923 and the one for Sunday 19 June 1910 simply records: “Slept, woke up, slept, woke up, miserable life.” Ross Benjamin’s new translation of the complete, uncensored diaries reveals a deeply idiosyncratic writer who felt forsaken for much of his life.

There are lots of quirky details about President Lincoln in Erik Larson’s The Demon of Unrest: Abraham Lincoln & America’s Road to Civil War (William Collins), including his ability to walk with a stoop and sport a fur hat to avoid being recognised. He also had a propensity to crack jokes, tell corny anecdotes and then escape unwelcome conversations by using the cover of laughter breaking out. Old Abe was also known for his occasional bluntness, and shocked former Virginia governor William Cabell Rives by telling him “you are a smaller man than I supposed”. Larson’s carefully pieced together story – using diaries, war communiques and slave ledgers – details the five months before America’s civil war. It is a thoughtful account that also offers a sobering reminder of how humans often don’t see a catastrophe coming until it’s too late.

Finally, Willy Vlautin’s novel The Horse (Faber), about a wandering guitarist called Al Ward who settles in Nevada and is visited by a strange horse, is a beguiling examination of loneliness, alcoholism and anxiety – and the beauty of songwriting.

Novels by Colm Tóibín and Kaliane Bradley, a book of happy poems, memoirs by Graham Caveney and Dr Benji Waterhouse, and Daisy Dunn’s classical history book are reviewed in full below.

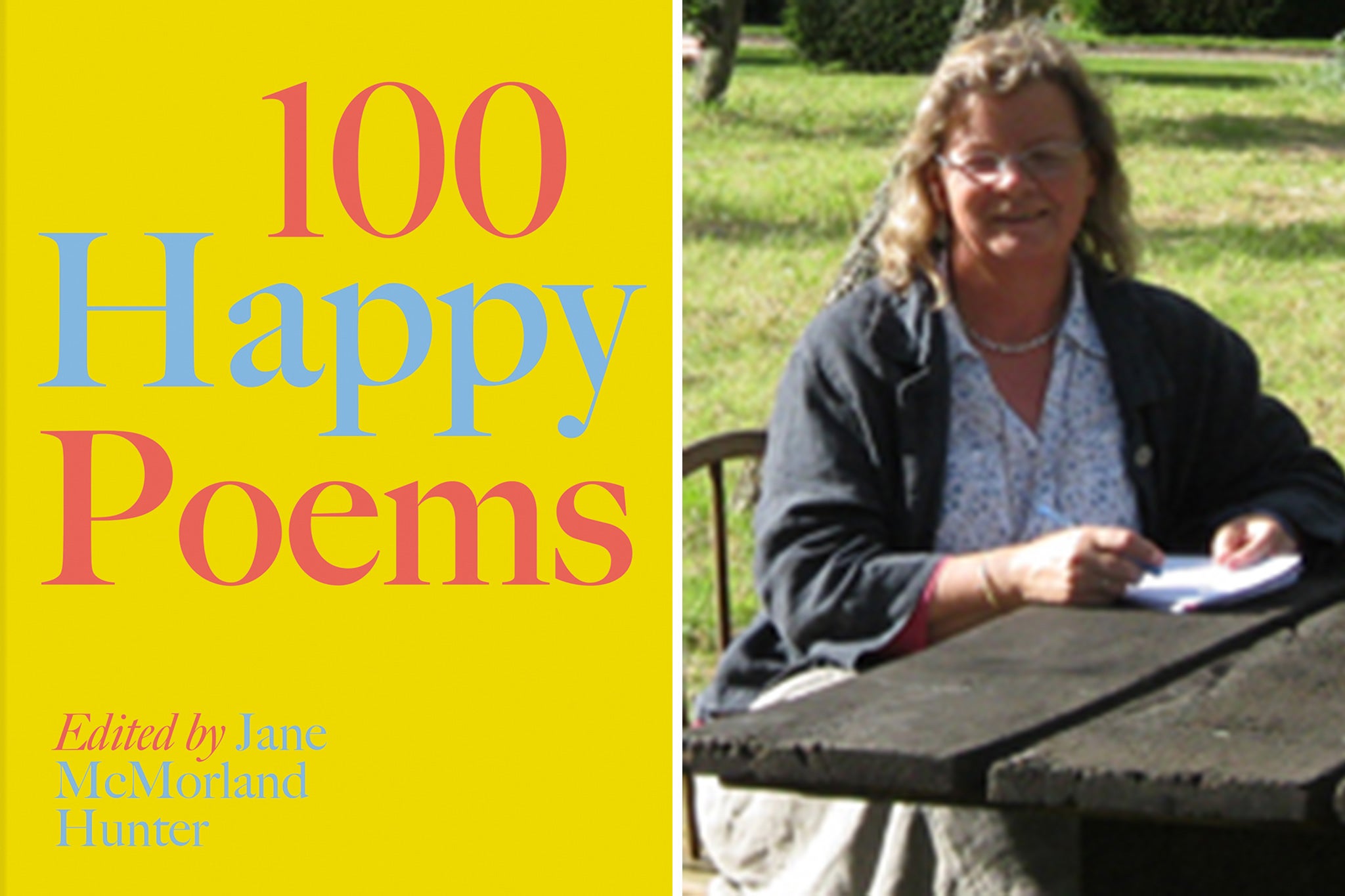

100 Happy Poems, edited by Jane McMorland Hunter ★★★☆☆

I recently watched a Devon stonemason beaming with contentment as he carefully selected stones with the “right face” to rebuild a wall. “Ah, he’s as happy as a pig in s*** when he’s working with old stone,” remarked his friend. As 100 Happy Poems editor Jane McMorland Hunter notes, many activities bring us happiness, including reading, singing, dancing, gardening and loving our pets.

The poems in the collection, selected from over a thousand years, capture various states of bliss. Stevie Smith is full of zest about the power of a “beautiful, beautiful kiss”.

For what it’s worth, my favourite was the one-stanza “First Fig”, an ambiguous gem from Edna St Vincent Millay, who died in 1950 and is hopefully remembered by some 21st-century readers, not least for being a feminist writer in the 1920s and only the third woman ever to be awarded the Pulitzer prize. She wrote:

“My candle burns at both ends; / It will not last the night; / But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends – / It gives a lovely light!”

Unsurprisingly, there’s no place for Philip Larkin in the anthology but then again the old curmudgeon did concede that “my poems aren’t very cheerful”. These 100 certainly are.

100 Happy Poems, edited by Jane McMorland Hunter is published by Batsford on 9 May, £12.99

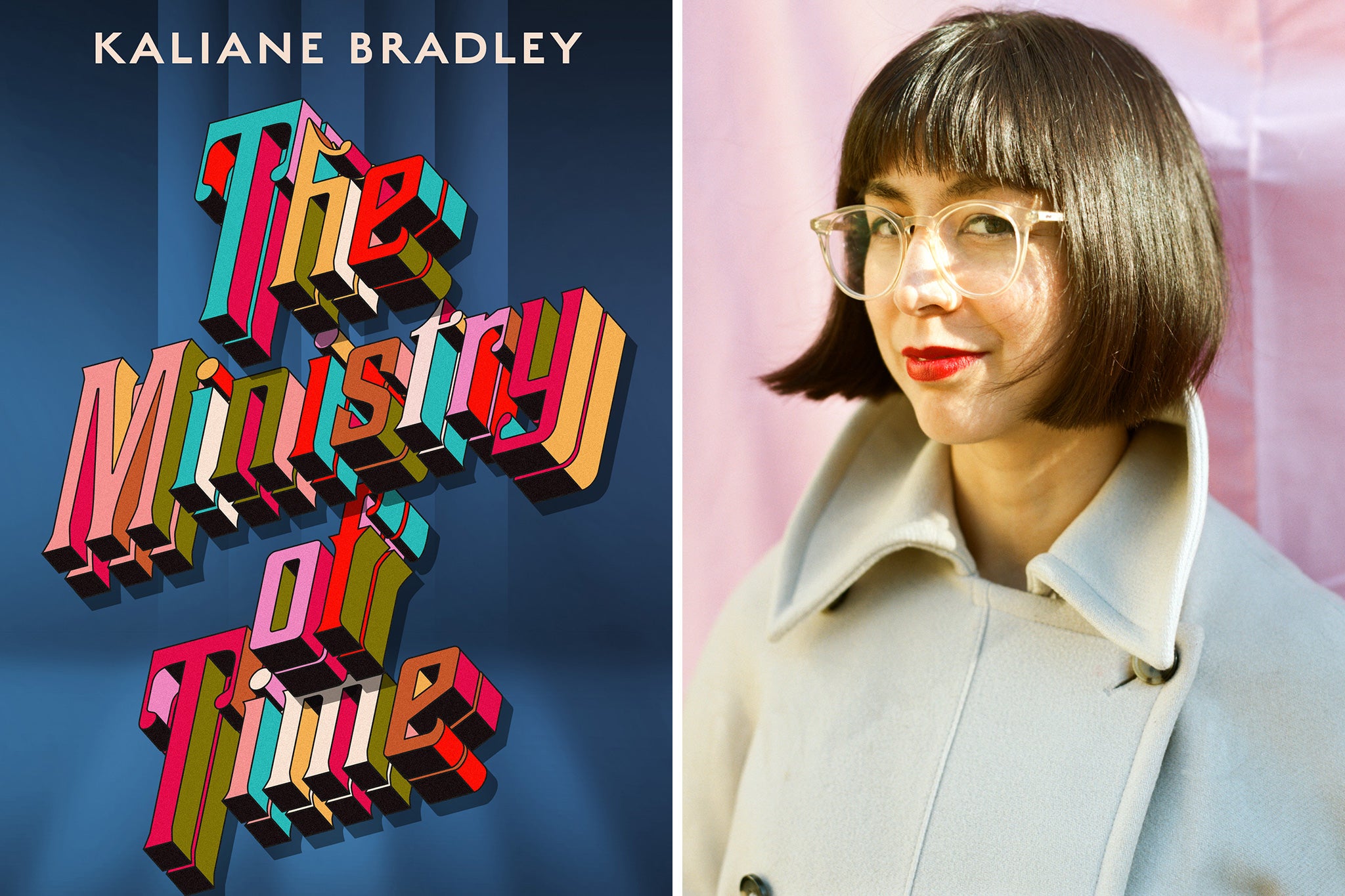

The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley ★★★☆☆

In Kaliane Bradley’s debut novel The Ministry of Time, which is a mixture of time travel sci-fi thriller, historical fiction and romance, Commander Graham Gore, an officer on Sir John Franklin’s doomed Arctic expedition, is one of a number of “expats” from the past rescued from certain death by the Ministry of Time. They are all allocated a person known as a “bridge” to assist them with living in the 21st century. The plot revolves around secret projects and conspiracies.

For the record, the BBC announced earlier this year that they have commissioned an adaptation of Bradley’s book. I’ve not seen the successful, long-running Spanish time travel television series El Ministerio del Tiempo (The Ministry of Time) but did read Bradley had issued a statement in response to complaints about alleged similarities saying: “My debut novel is an original work of fiction. I have never seen the Spanish television series and the identical titles are an unfortunate coincidence.”

Time travel is a well-worn subject, of course, but Bradley brings a freshness to her story of the growing love affair between Gore and his biracial British-Cambodian handler. Throughout the book, I particularly enjoyed the flashback sections imagining Gore’s life on the doomed frozen expedition in the 1840s. They were well executed and full of insightful imagining. In addition, putting time travellers into the present allows Bradley the potential for comic moments – such as Commander Gore liking Motown and describing the Beatles as “awful caterwaulers”.

The book attracted extravagant pre-release praise so perhaps it’s a failing on my part not to have been blown away by the book. The future, in case you wonder, is a pretty bleak one, blighted by crop-destroying chemical weapons and a climate-wrecked Devon.

I did have minor quibbles: some of the similes are a bit weak and I’m not sure I’d ever accept as convincing the description of Guinness as “angry Marmite”. Nevertheless, The Ministry of Time is a high-energy story with thoughtful things to say about belonging (Bradley, a British-Cambodian writer also has acute observations about racial prejudice, stereotyping and the “fine British tradition of finders-keepers”).

Above all, the novel seems to be a plea for humanity. As Gore says of his Ministry of Truth handler and lover, “in the heat of your obsession, did it occur to you to remember that I am a person too?”

The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley is published by Sceptre on 14 May, £16.99

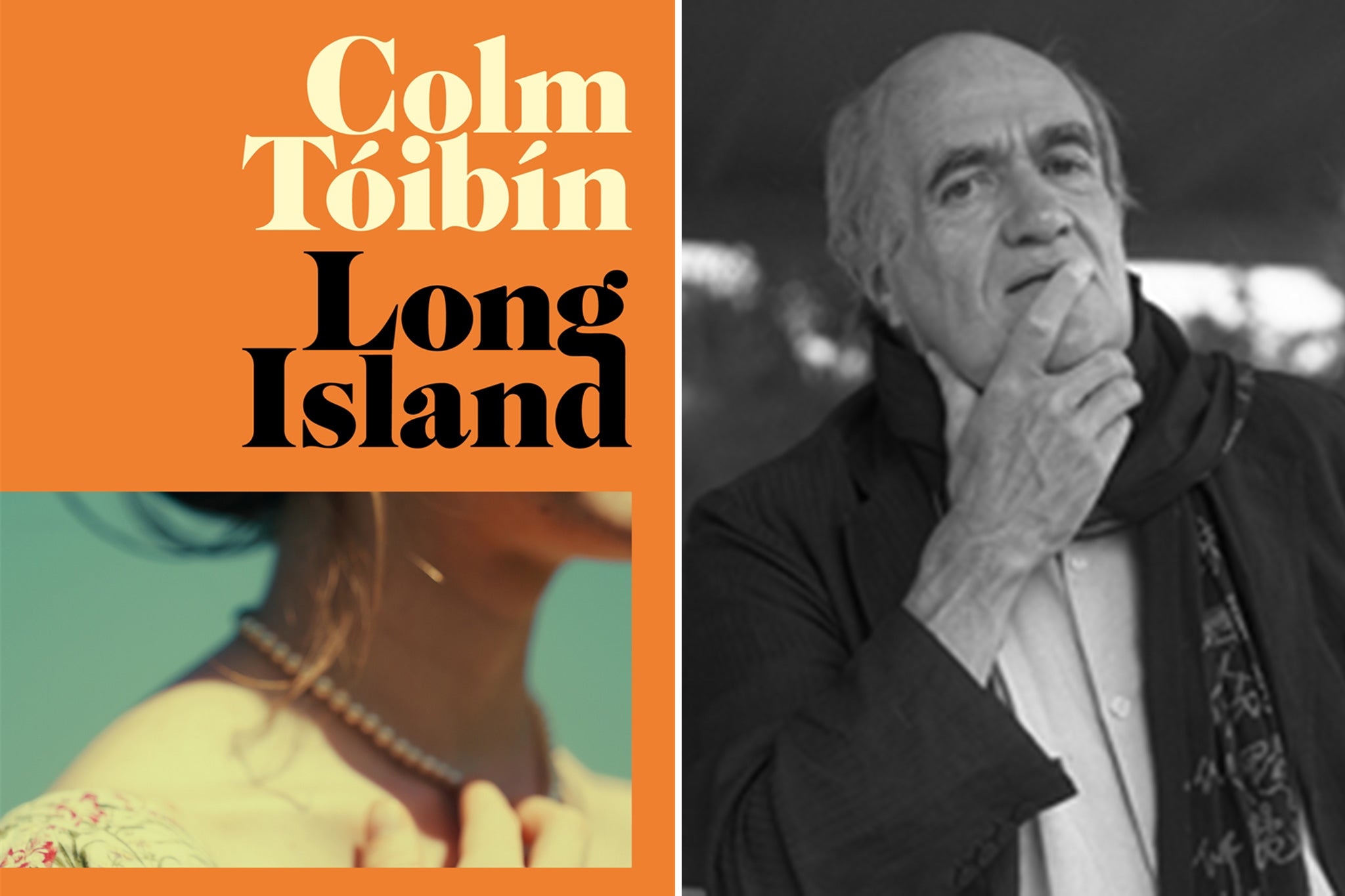

Long Island by Colm Tóibín ★★★★★

Colm Tóibín – the present laureate for Irish fiction – returns to the story of Eilis Fiorello (Lacey) in Long Island, the sequel to his magnificent 2009 novel Brooklyn. Some 20 years on from the action in that 1950s novel, we first see Eilis’s stifled life in New York, as a dutiful mother who is surrounded by her husband’s overbearing family. She is thrown into turmoil when a stranger arrives at her door with a shocking, terrible revelation about her plumber husband Tony, one of many morally feeble men in the novel.

To escape her crisis, she returns “home” to Enniscorthy, a small town in County Wexford in the east of Ireland – the birthplace of Tóibín and the backdrop to Brooklyn and the excellent Nora Webster – to stay with her ageing mother and insipid brother.

As she begins to really question the life she has built in America, she is forced to examine what she wants and whether the answer is reigniting a love affair with the publican Jim Farrell. Into the mix comes Nancy, another character who first appeared in Brooklyn, who is now widowed and running a chip shop. Nancy’s decisive scenes are absolutely gripping.

Tóibín guides everything with a master’s hand, in what becomes a tale of denial, secrecy, hidden resentments and disappointments. Eilis is again superbly drawn, as Tóibín offers a mesmerising and understated picture of Ireland in the mid-1970s (a chat about the disgrace of Nixon is the only time global affairs are discussed) and how, after her two decades away, Eilis is both an outsider and emblematic of a loss of innocence in Irish women of her era.

She remains something of the mysterious, blank protagonist of Brooklyn, yet in Long Island she is more knowing too, full of complex undercurrents. She is a great “noticer” and reflects on her life without necessarily being able to decide what she wants or whether she is capable of true feeling.

Tóibín brings the novel to a boil with cool detachment and leaves the finale open to interpretation – and to a possible trilogy concluder? Another outing with Eilis would be most welcome, but for now I’d urge any fiction fan to relish another Tóibín triumph.

Long Island by Colm Tóibín is published by Picador on 23 May, £20

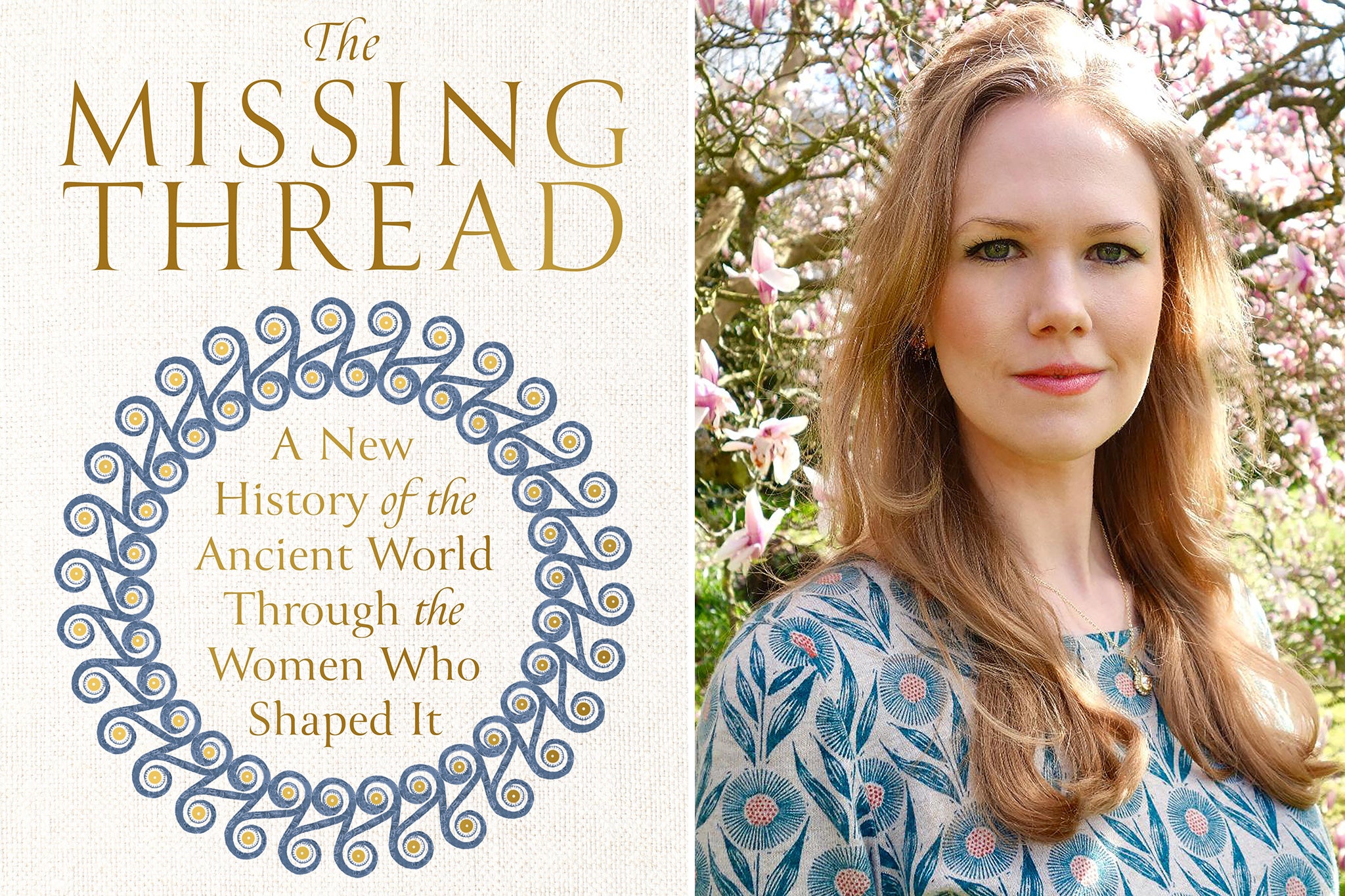

The Missing Thread: A New History of the Ancient World Through the Women Who Shaped It by Daisy Dunn ★★★★☆

Daisy Dunn opens her groundbreaking history of the ancient world with a sardonic reflection: “Women were invented to make men’s lives more difficult,” she writes, as she dissects the Greek poet (farmer) Hesiod’s warning to “let no woman deceive your mind with her shapely bottom / And wheedling conversation. It’s your barn she is seeking.”

Dunn’s barnstorming book explores the stories of dozens of women, including the poet Sappho, the fighters Telesilla and Artemisia, the only female commander in the Greco-Persian wars (499-449BC). As well as being a well-researched and elegantly written counterpoint to the way men have dominated the histories of antiquity, she has an eye for the quirky, revealing detail. I admit I knew nothing of Mark Antony’s forgotten wife Fulvia (everyone knows about his lover Cleopatra, of course) and Dunn records that the “astonishingly accomplished” Fulvia fought a war in Antony’s name while he was continuing his affair. “I had read these passages with suspicion,” Dunn writes, “until I learned of the excavation of lead bullets referencing Fulvia at the site of a siege. These bullets bore messages of abuse. ‘I’m aiming for Fulvia’s clitoris,’ reads one.”

Dunn’s spirited work not only puts the overlooked women at the core of the narrative, but it also reminds us that the past, particularly with sexism and misogyny, has vital lessons for the 21st-century present.

The Missing Thread: A New History of the Ancient World Through the Women Who Shaped It by Daisy Dunn is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson on 23 May, £25

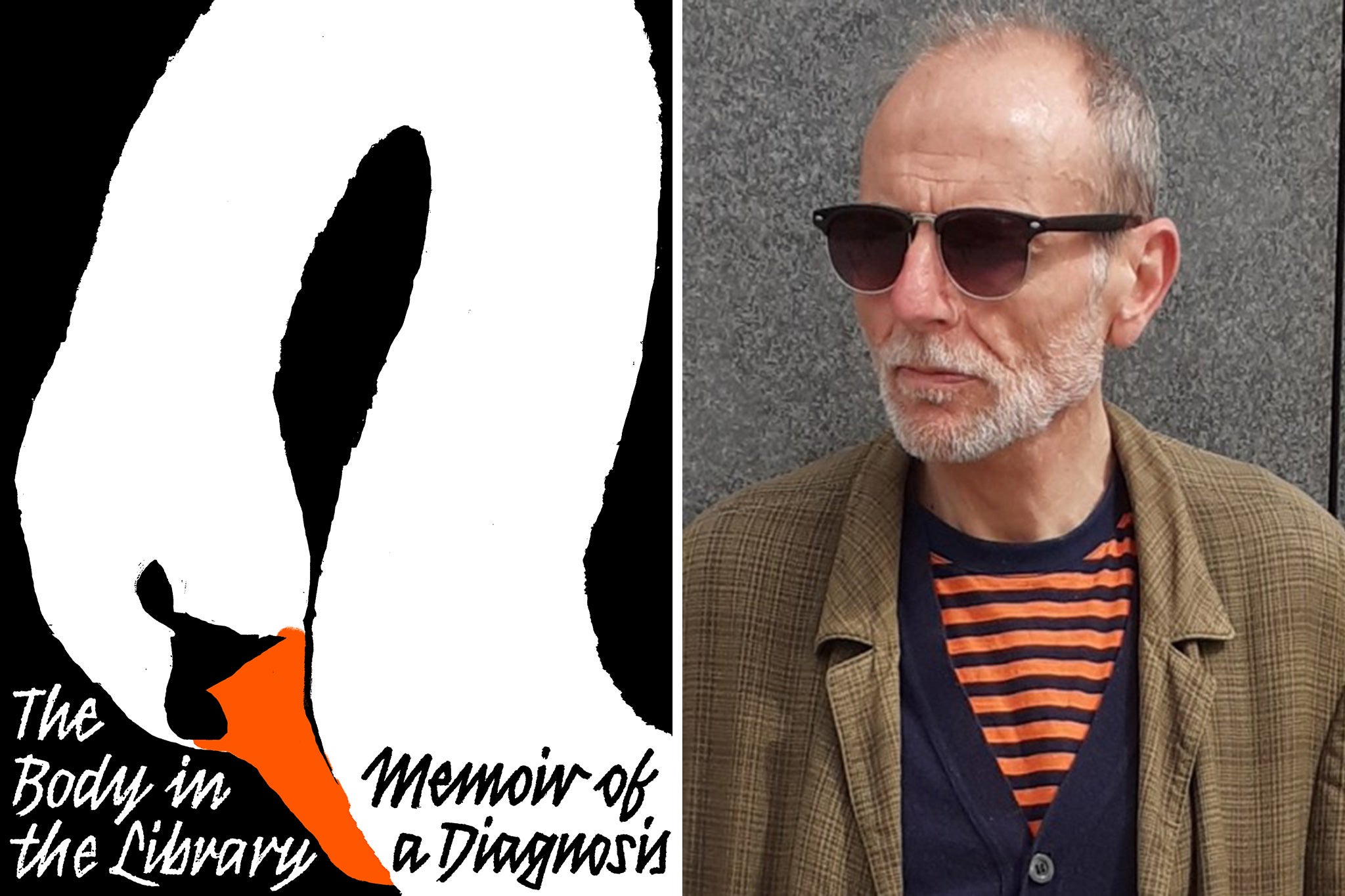

The Body in the Library by Graham Caveney ★★★★★

Anyone who has had the misfortune to undergo an endoscopy will be struck by Graham Caveney’s observation on being told it is a routine procedure. “It raises the question: whose routine?”, he writes in The Body in the Library.

Caveney’s latest memoir, a moving and humorous account of having cancer of the oesophagus, made me grimace and laugh. He calls himself “an impatient outpatient” and even throws in some jokes. Here’s one: Guy goes to the doctor. The doctor gives him six months to live. The guy says, I want a second opinion. Doctor says, Second opinion? Sure. That tie doesn’t suit you.

As he details his diagnosis and treatment (no spoilers but the remission part is good news), the book deals with his anxiety and his anger at the Tory government’s destruction of the NHS, something he sums up smartly as “incremental vandalism”.

In his delightful introduction, Jonathan Coe calls the book “a small masterpiece” and you have to admire Caveney’s gift for terrific one-liners. He describes Hattie Jacques in Carry on Nurse as “a one-woman nanny state”, for example, and his account of drinking with the late Pogues’ frontman Shane MacGowan (a Turgenev fan) is charming, describing his laugh as “a deranged bronchial hiss; like a snake trapped in the bonnet of an overheated car”. The mention of Turgenev is enlightening in a book full of literary references. I enjoyed his witty ruminations on why Philip Larkin is out of favour. “We no longer swallow him: not exactly cancelled, but shushed. An ironic end for a librarian,” writes Caveney.

There is much about love and work in a gnarly, sweet book that also deals with sexual abuse (a theme of his earlier work). Anyone who has been close to alcoholism will see the mordant wisdom in his recollection of what an ex-street drunk told him, early in his sobriety quest. “It’s a good news bad news joke. The good news is you get your emotions back. The bad news is… you get your emotions back. Strap in, kid.”

Buckle up, indeed, because The Body in the Library is a bumpy, brilliant read.

The Body in the Library by Graham Caveney is published by Peninsula Press on 30 May, £12.99

You Don’t Have to be Mad to Work Here: A Psychiatrist’s Life by Dr Benji Waterhouse ★★★★☆

Benji Waterhouse is a “firefighting NHS psychiatrist” and a stand-up comedian who uses humour as a defence against the messiness of life. One nurse calls him out on this, remarking wearily after another of his quips: “Oh, you’re one of those funny ones. Aren’t we lucky”.

You Don’t Have to be Mad to Work Here: A Psychiatrist’s Life is an account of Waterhouse’s patients, his family and his own struggles with depression and being “avoidant in love”. It’s certainly funny, mixing humour with intense pain. His parents are spiky characters in their own right. He is forced to confront whether his father’s temper has handed down the trait of behaving with a veneer of gentleness that is just “repressed aggression”. He has also learned to cope with the drunken idiosyncrasies of his mum, a psychologist who responded to him bringing home a female friend called Nina by whispering in his ear, even before she’d had a chance to take off her coat, that “she’s not the one for you sweetheart”.

The anecdotes are wild and the reflections interesting. To find real pleasure in a memoir you have to enjoy spending time with that writer, and I did with Benji, not least for documenting the time he was offered ketamine at a party, and admitted he would rather have a cup of tea. “I’ve been told off before for boiling the kettle at parties,” is his droll punchline.

For all the anarchy and comedy with patients, Dr Waterhouse is insightful about mental health in an era of overused sad face emojis and a scarcity of NHS psychiatric beds. For example, it’s instructive to learn that restrictions on over-the-counter sales have significantly reduced fatalities from paracetamol overdoses and important to hear that “contrary to popular belief, talking about suicide doesn’t increase but decreases the likelihood that people will act on such impulses”.

Psychiatrists have notoriously high levels of mental illness themselves – unsurprising given their working lives are spent around human distress – and when Waterhouse tells his therapist that he didn’t expect the work to be as chaotic, frustrating and knackering, the therapist replies: “Not exactly Frasier, is it?” Even so, Benji is worth listening to.

You Don’t Have to be Mad to Work Here: A Psychiatrist’s Life by Dr Benji Waterhouse is published by Vintage on 16 May, £18.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments