Books of the month: what to read this January

Martin Chilton shares his January reading highlights

This year promises to be another exciting outing for fiction, including February’s publication of We Do Not Part, the first novel by South Korean author Han Kang since she won the Nobel Prize for literature in October. January welcomes promising debut authors, such as Catherine Airey with Confessions, as well as an autobiography from Pope Francis, the first book written by a sitting pope, and a fine adult novel (So Thrilled For You) by young adult writer Holly Bourne.

This column is changing up its format this year, and going forward, will be spotlighting the best fiction, biography and non-fiction of the month. Airey’s novel, a biography of James Dean and a groundbreaking new study of racism by Keon West are reviewed in full below.

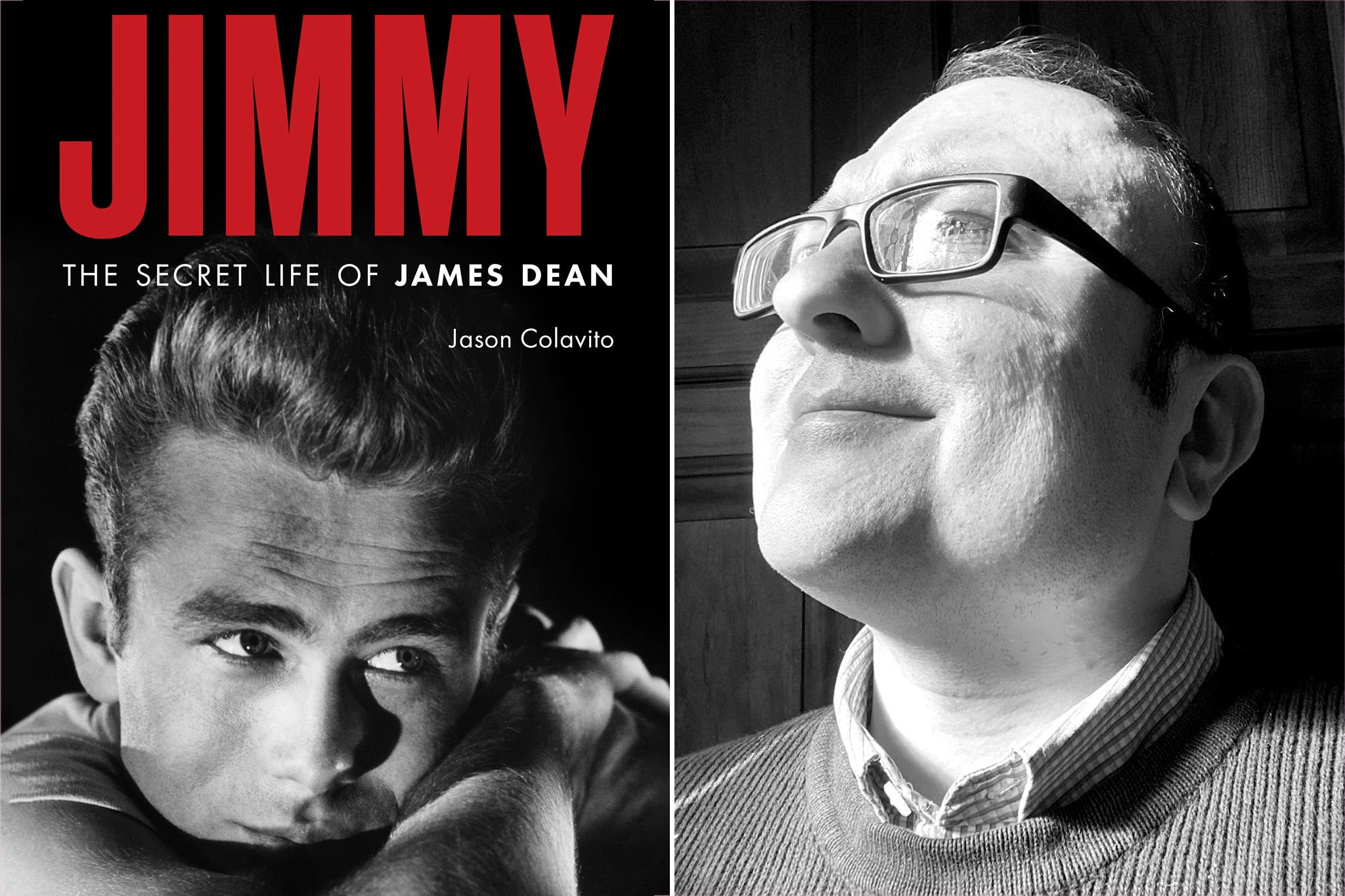

Biography of the month: Jimmy: The Secret Life of James Dean by Jason Colavito

★★★★☆

James Dean’s two psychoanalysts don’t seem to have done much to earn their corn. In a letter addressed to “girlfriend” Barbara Glenn in 1954 – a year before his death at the age of 24 – the Hollywood icon admitted that he was a mess. “Wow! Am I f***ed up,” he wrote.

As one of the most famous actors of the 20th century, Dean has been the subject of numerous biographies. This is the first I have read, so I can’t offer comparisons. But what I can avow is that in Jimmy: The Secret Life of James Dean, author Jason Colavito offers a sympathetic, discerning account of Dean’s life set in the context of the antigay panic of the 1950s.

The star of East of Eden, Rebel Without a Cause (both 1955) andThe Giant (1956) was a conflicted, volatile, and self-dramatizing youngster from the Midwest. His father was absent and his mother died of cancer when he was just nine. Stardom was his goal even as a troubled child. His Giant co-star Elizabeth Taylor recognised that his wounds “cut deep”, including the experience of having been sexually abused as a boy by Reverend James DeWeerd, a Wesleyan Methodist minister in Indiana known to the more observant locals as “Dr Weird”.

Colavito does a good job of cataloguing Dean’s quirky behaviour, explaining why writers, directors, and luminaries such as Marilyn Monroe, Rock Hudson and Marlon Brando took such an intense dislike to him. It also does well to paint a compelling picture of Dean’s surroundings: a predatory and hypocritical Hollywood. Dean called it as he saw it, deeming the lecherous executives who targeted him “vampires” and writing, once success came in the mid-1950s, that “I refuse to be sucked into things of that nature [pun, ha ha]”.

The film studios tried to push an image of Dean as a womaniser and although Dean was bisexual, he never seemed to relish dating or sleeping with women. He would baffle attractive girls on dates, either with his total lack of interest or his habit of showing them crude drawings of men having sex. He was complicit in the studio cover-up, however, with Colavito concluding that “Dean worked tirelessly to manage his image”, even paying off a blackmailer who threatened to leak knowledge of his male lovers.

The accompanying photographs are striking and although the writing is occasionally gushing (with a fondness for the word “bifurcating”), Colavito’s book offers a perceptive study of the strange era that caused Dean such torment. The real story of Rebel Without a Cause, for example, is grim, with actor Sal Mineo (who described his character Plato as “in a way the first gay teenager in films”) being ostracized by many in the cast because of his “obvious homosexuality”. Meanwhile, director Nicholas Ray, then 43, was having sex with 16-year-old co-star Natalie Wood, in violation of California’s statutory rape laws.

Dean was well-read – his favourite authors included Federico Garcia Lorca and Albert Camus, whose pose he mimicked – and a supreme athlete. He was also indifferent to physical danger; in the end, it was wild driving that played a part in his tragic demise. Colavito is equally revealing about the media circus that followed Dean’s death. The most pitiful detail (for me, anyway) is that it was DeWeerd who was allowed to preside over his funeral.

‘Jimmy: The Secret Life of James Dean by Jason Colavito’ is published by Applause on 19 January, £25

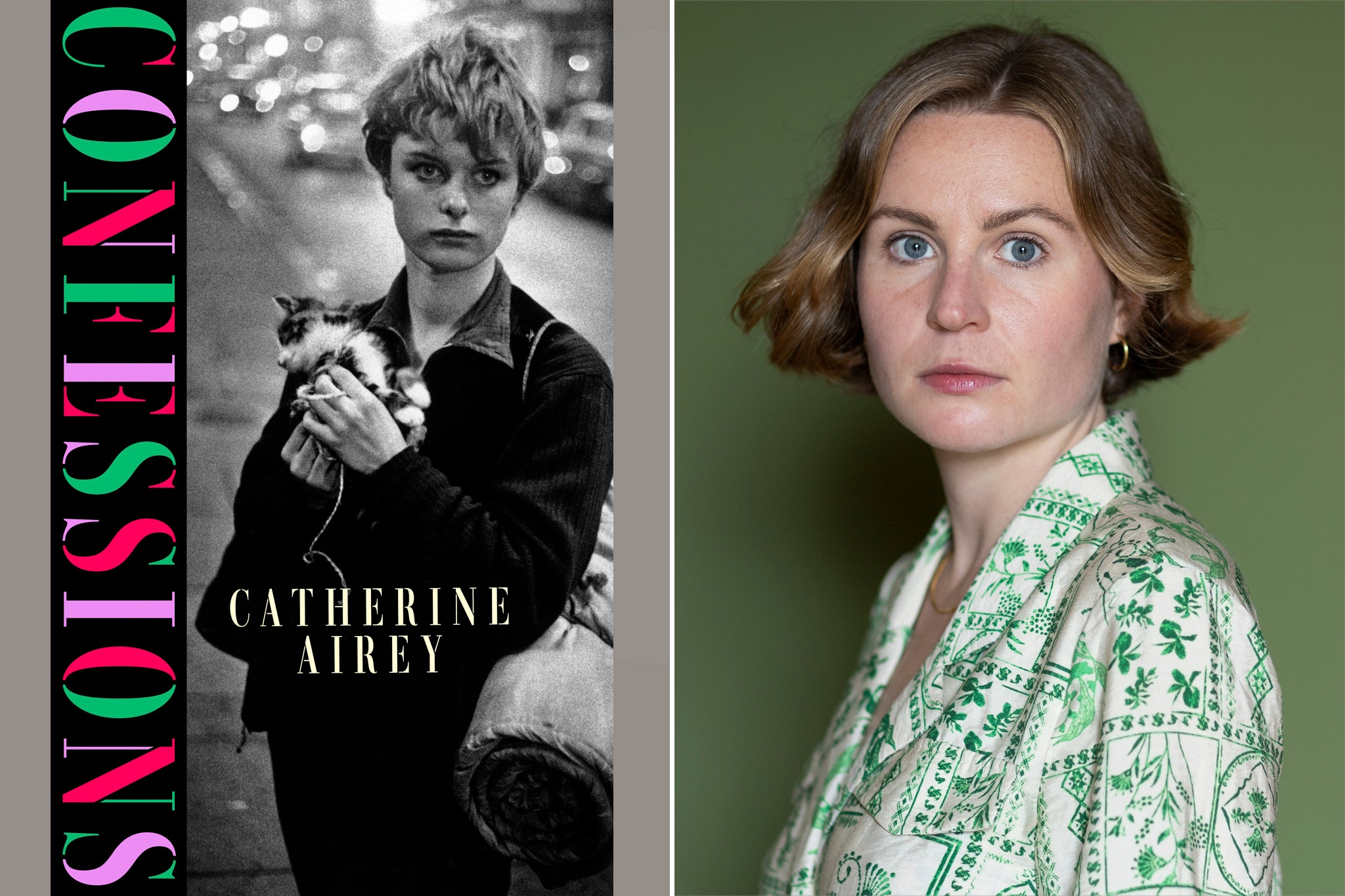

Novel of the month: Confessions by Catherine Airey

★★★★☆

Catherine Airey’s impressive debut novel Confessions traces the arc of three generations of women, switching from New York to rural Ireland and back again. In the novel, Airey deals with family secrets, love and tragedy, mental health, misogyny and the displacement and heartache of Irish migration.

Airey, who studied English at Cambridge and worked in publishing and as a copywriter for the civil service before turning to fiction writing, opens Confessions with panache, in a chapter set in New York, 2001. It is here that 16-year-old Cora Brady is left orphaned when her father, Michael, dies in the 9/11 terrorist attack. She spends weeks wandering the city in a daze – allowing the set up for a droll line about a Twix bar and the Twin Towers – until she receives a letter from her aunt Róisín, the younger sister of Cora’s late mother Máire, offering her refuge in a small town in Donegal.

Confessions was initially titled Scream School, the name of Róisín’s video game from the 1980s that serves as both a framing device and a turning point in the plot. Over shifting narrative and flashback sequences, Airey deftly pieces together the story of what happened to the sisters and the mystery surrounding Cora’s daughter Lyca. In the process, Airey excavates the secrets and traumas of a family’s messy history, uncovering suicide and sexual abuse. Real events – Charles and Diana’s wedding, Bobby Sands’ death, the AIDS crisis – flicker in the background of a story that also deals with the battle for reproductive rights, sibling rivalry and the search for forgiveness.

Confessions sags in places (hardly surprising for a multilayered debut told over 461 pages), but it is strong on character and plot structure. Airey has taken flight with a well-written, engaging first novel.

‘Confessions’ by Catherine Airey is published by Viking on 23 January, £16.99

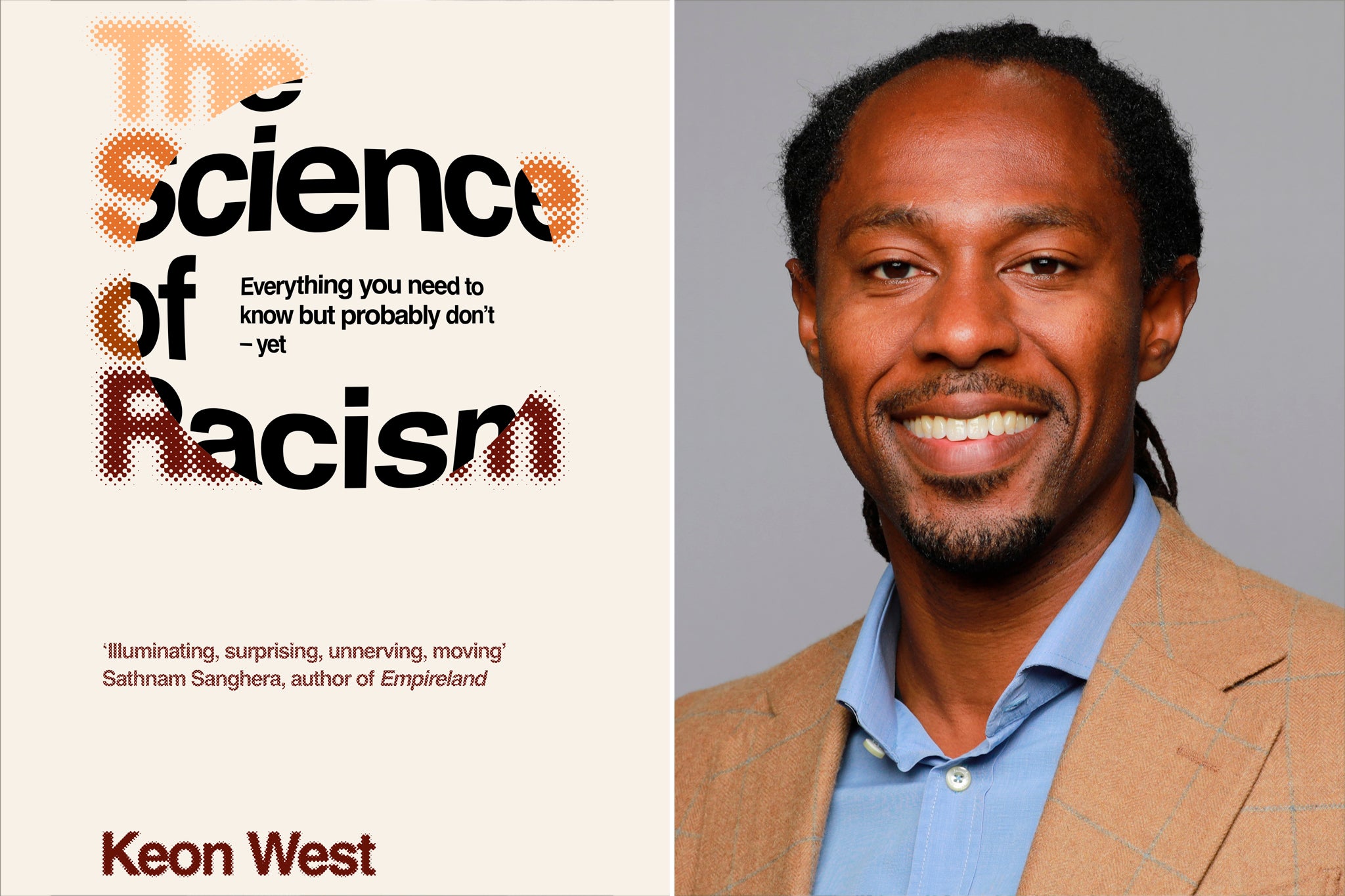

Non-fiction of the month: The Science of Racism: Everything You Need to Know But Probably Don’t – Yet by Keon West

★★★★☆

There are several passages in Keon West’s The Science of Racism that almost short-circuit the brain, simply due to the sheer overload of bleak information at the heart of this rigorous study of racism.

West, a professor at the University of London and president of the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, presents evidence to argue there is no aspect of life unaffected by racism. His complex yet still accessible book paints a devastating picture of what life is like for ethnic minorities in predominantly white countries, including the UK – where unemployment rates among Black people are twice as high; where police are nine times more likely to use their tasers on Black people; where 98 per cent of CEOs are white, etcetera, etcetera.

West casts a cold, scientific eye on a range of topics – including systemic racism, victim blaming, racial hierarchy and media stereotypes – and he does not shy away from offering his own potent views, such as why “colour blindness” as a cure for racism is “a terrible idea”. His tone is sharp, sardonic, and occasionally blunt, as when he describes Tory MP Ben Bradley’s views on “Orwellian” unconscious bias training as something that “is, from a scientific perspective, bollocks”.

The small, telling details are particularly dismal, including the fact that baseball cards featuring a Black player’s hand will sell on eBay for 20 per cent less than those that feature a white person’s hand. The single most depressing thing in the book is his account of what happened when a famous 1947 experiment on children’s racial preferences with dolls was repeated as recently as 2021. The results are, like much of West’s book, truly chilling.

Given that we are a quarter of the way into the 21st century and discrimination is clearly not fading, The Science of Racism is a bleak, essential read.

The Science of Racism: Everything You Need to Know But Probably Don’t – Yet by Keon West is published by Picador on 23 January 2025, £18.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments