Books of the month: From Jonathan Coe’s Bournville to Bob Dylan’s essays

Martin Chilton reviews November’s biggest books for our monthly column

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If books by the mega famous are your thing, then November has its usual share of starry contenders, including memoirs from Michelle Obama, Martin Kemp and Matthew Perry. My preference, though, was for something more offbeat, and screenwriter David Milch’s candid, outlandish autobiography Life’s Work is among the six books reviewed in full below.

That sextet includes Bob Dylan’s essays on music, the biggest non-fiction release this month. Also worth a look at is Cleopatra: Her History, Her Myth (Yale University Press), in which Francine Prose offers a feminist reinterpretation of the life of the Egyptian queen. Her chapter “Cleopatra on Film” features biting observations on the Hollywood objectification of a woman who, in real life, spent more time deciding about irrigation systems than slinking round in transparent sarongs. Of the historic 1917 film starring Theda Bara as Cleopatra, Prose remarks: “What did the film say to men? Women, especially Eastern women, were scheming, heartless, deceitful, and half-crazed with lust and sin.”

In Russia’s War on Everybody: And What it Means for You (Bloomsbury), expert Keir Giles gives a chilling account of what is happening in the land of Vladimir Putin (attack on Ukraine aside), including “irresponsible brinkmanship with aircraft, abuse of electronic warfare capabilities, economic warfare like trade embargoes and energy challenges, and soft challenges like migrant dumping”. It is an important book, although it doesn’t really rank as bedtime comfort reading.

Fans of the late PJ O’Rourke’s journalism will find much to enjoy in The Funny Stuff: The Official P.J. O’Rourke Quotationary and Riffapedia (Grove Press, edited by Terry McDonell), which includes his reflections on the online world. “I go back and forth on the virtues of the Internet,” wrote the American satirist. “Sometimes I am awed by my instantaneous access to enormous troves of important information. ‘What was the name of the child actor who played Jerry Mathers’ pudgy best friend Larry on Leave it to Beaver?’ Other times I wonder, ‘whose idea was it to put every idiot in the world in touch with every other idiot?’”

Jonathan Coe’s Bournville is my pick of November’s fiction, and also out this month is Stella Maris (Picador), Cormac McCarthy’s coda to The Passenger (reviewed in October’s column), an engrossing tale that explains what was going on with Alicia, who died by suicide in the first instalment.

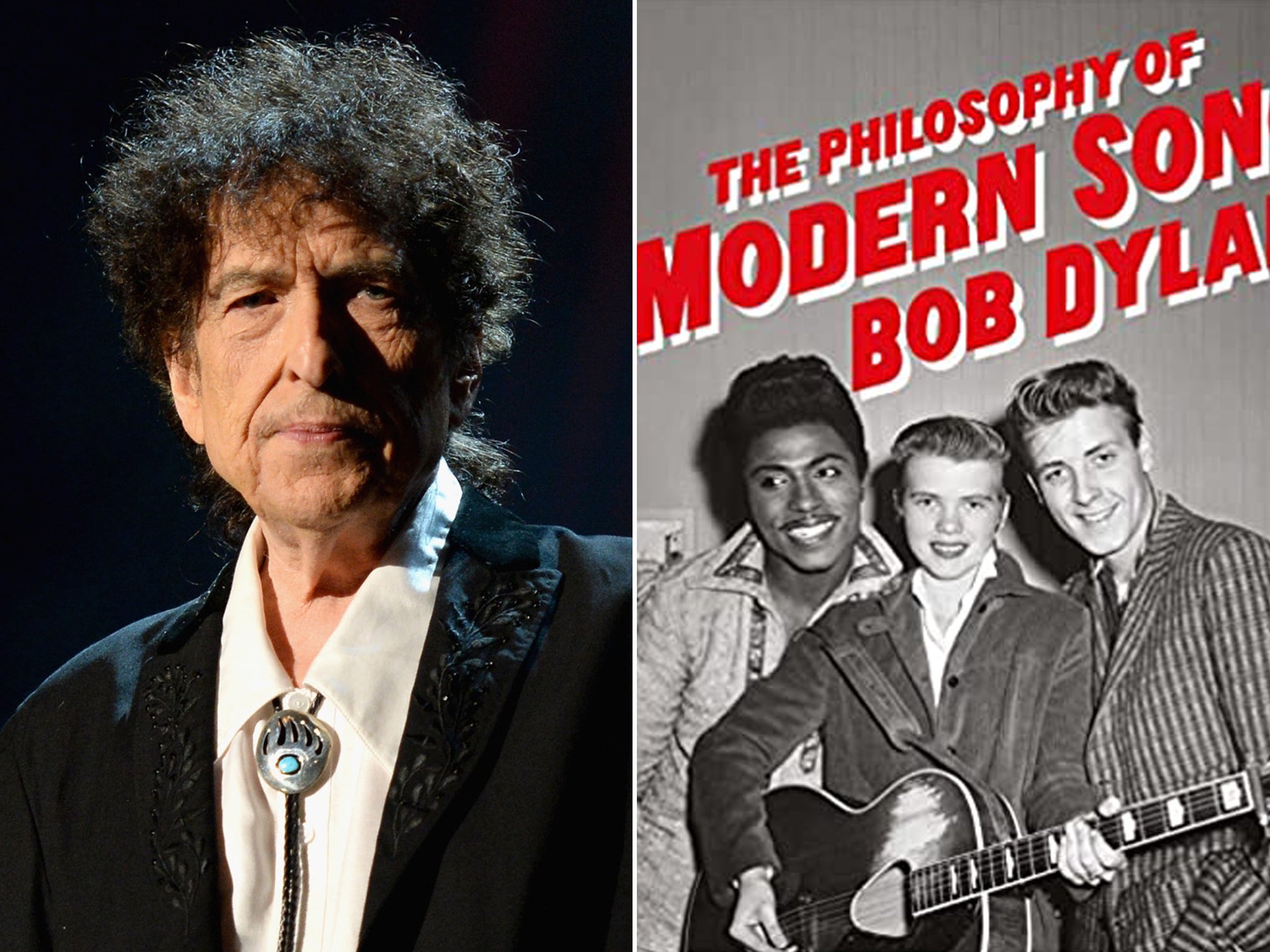

The Philosophy of Modern Song by Bob Dylan

★★★☆☆

It is 18 years since Bob Dylan published the excellent, revealing Chronicles, Volume One. Since that time, of course, the master songwriter claimed the Nobel Prize in Literature (2016).

Dylan began writing The Philosophy of Modern Song, which is dedicated to the late Doc Pomus, in 2010. Within its pages, the American offers 66 penetratingly original essays on compositions (works spanning Uncle Dave Macon in 1924 to Warren Zevon in 2003), analysing melodies, phrasing, musicianship and the meaning and context of lyrics. Dylan’s opinions are stimulating – he says of Elvis Costello’s “Pump it Up” that “the song has a lot of defects, but it knows how to conceal them all” – and highly idiosyncratic. Dylan, unquestionably a titan of music, is now 81, and he ruminates on ageing in his thought-provoking essay on Charlie Poole’s “Old and Only in the Way”.

It is heartening that Dylan includes songs by Townes Van Zandt (“a broken poetic soul”), Willie Nelson (“he could sing the phone book and make you weep”) and Billy Joe Shaver (“a philosophical point of view”), although one oddity is the scarcity of women songwriters (I counted only six, including Mrs Elmer Laird for “Poison Love”), and female singers: only three per cent of featured performers are women (Cher, Rosemary Clooney, Judy Garland and Nina Simone).

Music fans will certainly get a fantastic playlist using Dylan’s richly illustrated book and it’s fun to listen to the songs as you read his stimulating guide to what makes great lyrics “so damn enticing”. And who else but Dylan would remark of Eddy Arnold’s maudlin love song “You Don’t Know Me” that “a serial killer would sing this song, the lyrics kind of point toward that”?

The Philosophy of Modern Song by Bob Dylan is published by Simon & Schuster on 1 November, £35

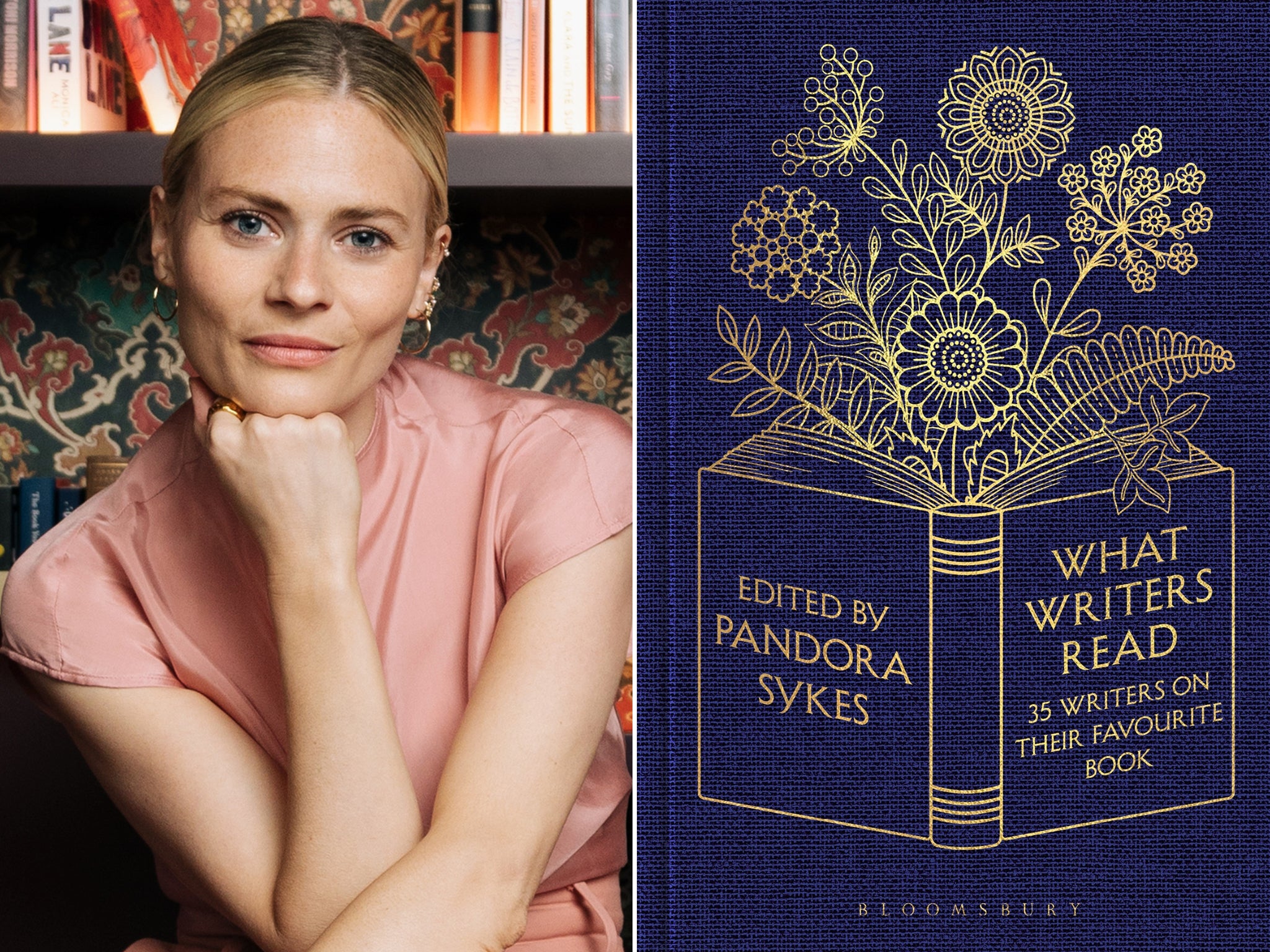

What Writers Read: 35 Writers on Their Favourite Book

★★★☆☆

Exceptional writers are almost always avid readers and in What Writers Read: 35 Writers on Their Favourite Book, editor Pandora Sykes has assembled an appealing cast to write about the books that mean something special to them. It is a wonderful “dip-in” publication, full of humour and insights. And, to cap it off, the profits and royalties go to the National Literacy Trust, which works to end literacy inequality.

Among the 35 authors giving their services for free is Elif Shafak, who describes the solace she found in Virginia Woolf’s fluid Orlando when she devoured it as a young bisexual woman growing up in a repressive Turkey. Among the other highlights are the short, pithy essays from Monica Ali (on Pride and Prejudice), William Boyd (on Catch-22), Lisa Taddeo’s witty confession about her own drunken behaviour (on Fever Dream) and Damon Galgut’s graceful tribute to the small gem Train Dreams.

Great literature is transformative, something Meena Kandasamy reminds us of in her entry about Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, a book she writes “will change the way you look at yourself. It will change the way you want to change the world.”

What Writers Read is a treat – one that will propel you on a journey of discovery.

What Writers Read: 35 Writers on Their Favourite Book, edited by Pandora Sykes, is published by Bloomsbury on 1 November, £12.99

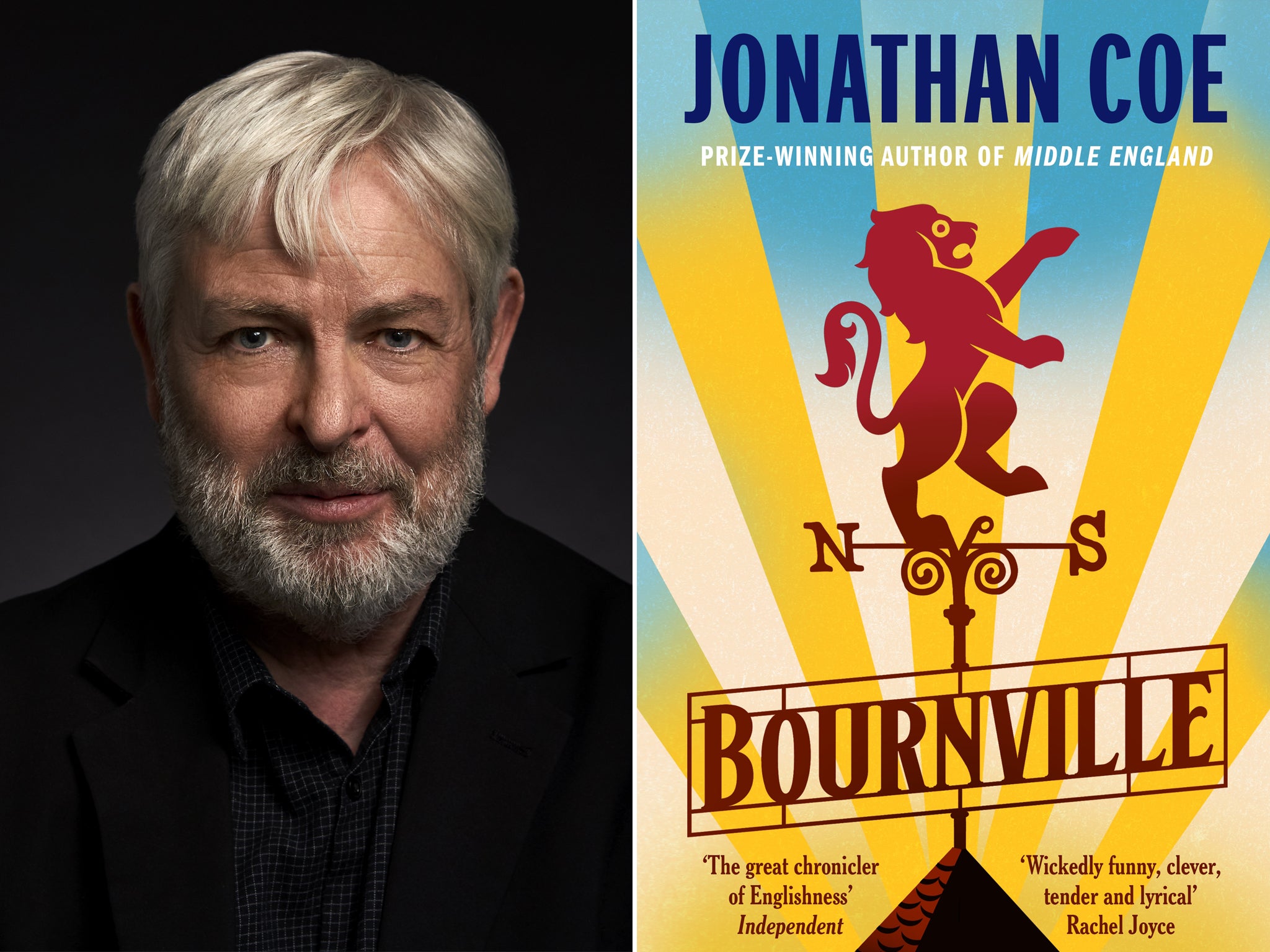

Bournville by Jonathan Coe

★★★★☆

Jonathan Coe’s Bournville follows four generations of a family from the Birmingham model village, which was founded by Cadbury in the 19th century. The novel is anchored by seven major events in UK history: VE Day in 1945, the 1953 coronation, the 1966 World Cup final, the 1969 investiture of the Prince of Wales, Charles and Diana’s 1981 wedding, Diana’s funeral in 1997, and the 75th anniversary of VE Day in May 2020.

The core characters are Mary and her husband Geoffrey, a model for the “frustratingly reserved and uncommunicative” men who were so prevalent in post-war Britain. Coe pulls off a neat trick shot in using Geoffrey’s tennis style to reveal his character. “Geoffrey was slow and guarded; intelligent and resourceful in his placement of the ball but handicapped by his cautious temperament,” writes Coe.

The story of Mary, Geoffrey and their sons, Jack, Martin and Peter, is told alongside that of the nation, as Coe wanders through 75 years of our past. There is an evocative description of the role of James Bond movies in the national psyche. The past is caught in small, astute details, as in the excitement Coe describes from 1949, when an enormous new television transmitter was erected on a hill near Sutton Coldfield, something presumably distinctly underwhelming to a 21st-century teenage gamer.

There is plenty of chocolate-related material for the sweet-toothed, and any football fan will love the section on England’s World Cup victory at Wembley, although it might be a twist too far to think that 10-year-old Jack came up with the cry, “two World Wars and one World Cup” on the spot in 1966.

The way the nation has changed is also shown in telling private reactions to global events. The reverence to royalty in 1945 is in stark contrast to a comment from a character in 1981, remarking on groom Prince Charles and his unromantic behaviour towards Diana. “If you ask me, he looks like he’d rather be having it off with her brother,” Kashifa says.

Mary ponders in old age about whether she has led a “small life”. We see her, frail and nostalgic, making a return to Bournville as a 75-year-old and failing to connect with the 11-year-old girl who had lived there once. It is one of the many touching scenes in an appealing story.

The “buffoon” Boris Johnson comes into a section set in Brussels (when his grift, in that era, was being an anti-EEC journalist). He reappears after fulfilling his ambition to be prime minister, and we see Johnson’s pandemic announcements in March 2020 through the shrewd eyes of Martin. “There was something weightless about the performance, as if the nation was being addressed by an empty vessel, a hologram of the prime minister rather than the real thing,” he remarks.

The way Coe starkly captures the paranoia and fear of the early days of the pandemic is impressive and he has written what he calls a “faithful account” of the death of his mother during lockdown. It is an intensely affecting finale.

In his moving “author’s note”, which I read on the day Johnson released the tawdry “thumbs-up” photograph of himself in the midst of his failed attempt to get back into power, Coe notes that, “Almost two years after the event, it still saddens and angers me that my mother died alone, without pain relief, and that members of her family were allowed no personal contact with her as it happened. But then, like thousands of families up and down the country – and unlike the occupants of number 10 Downing Street – we were following the rules.”

Bournville by Jonathan Coe is published by Viking on 3 November, £20

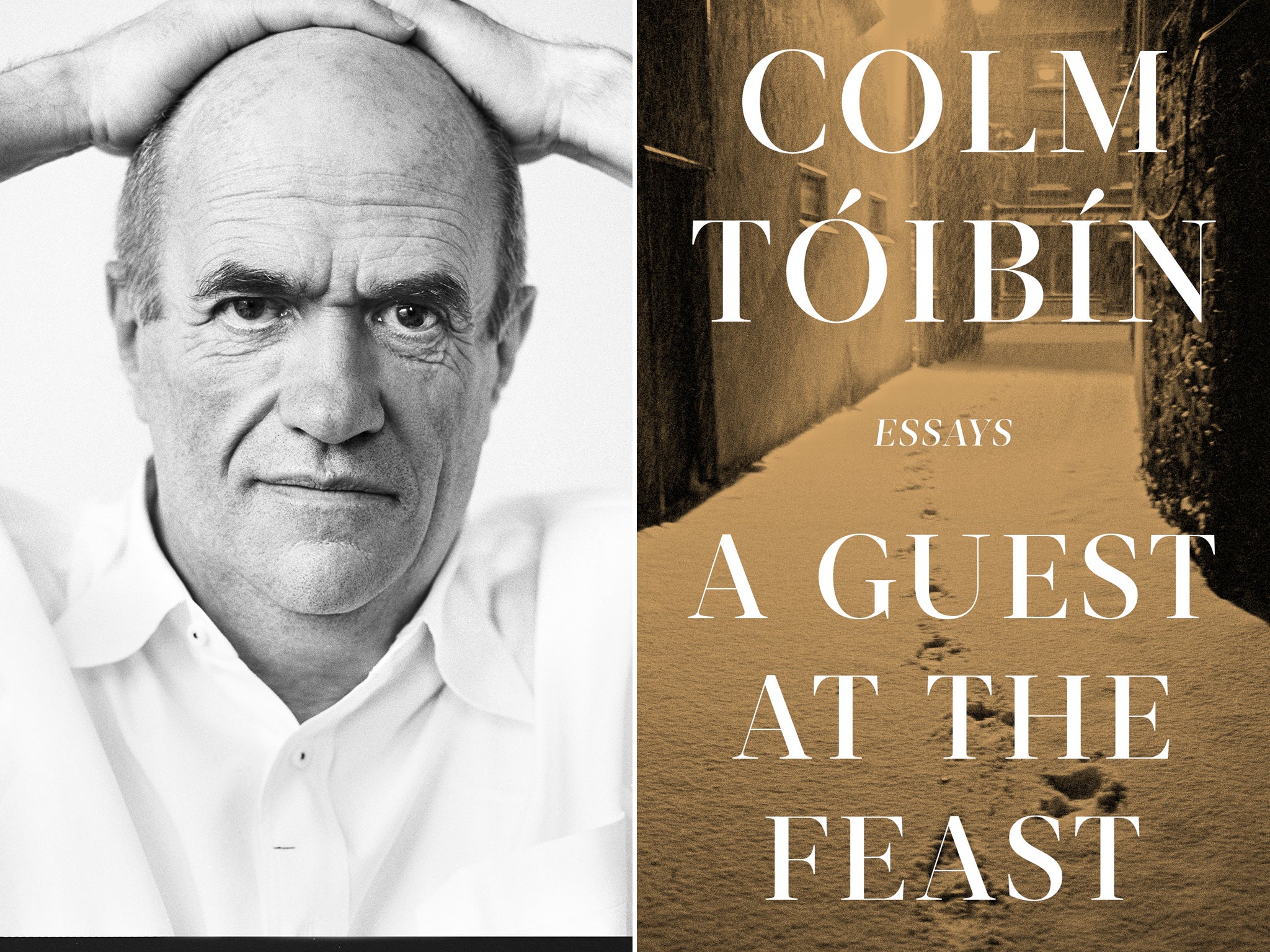

A Guest at the Feast: Essays by Colm Tóibín

★★★★☆

Reading Irish novelist, playwright and poet Colm Tóibín is always a delight, and his book of essays, A Guest at the Feast, is an unsurprisingly erudite, gracefully written unpicking of the world, with compelling reflections on fellow Irish writer John McGahern and American Marilynne Robinson.

A Guest at the Feast opens with a powerful 2019 essay on his cancer diagnosis, which started with a strange soreness in his right testicle. Seeking answers, he is required to strip naked for an ultrasound, whereupon he is told by one of the young male nurses that they know this must be “shaming” for him. Tóibín, born in 1945, recalled that, “I sat up, rested on my elbows and looked at him. ‘When you get to my age, I told him, ‘nothing is shaming.’”

The cancer, which spread to a lymph node and one lung, was cured. We can all be thankful for that, as this illuminating book proves.

A Guest at the Feast: Essays by Colm Tóibín is published by Viking on 3 November, £16.99

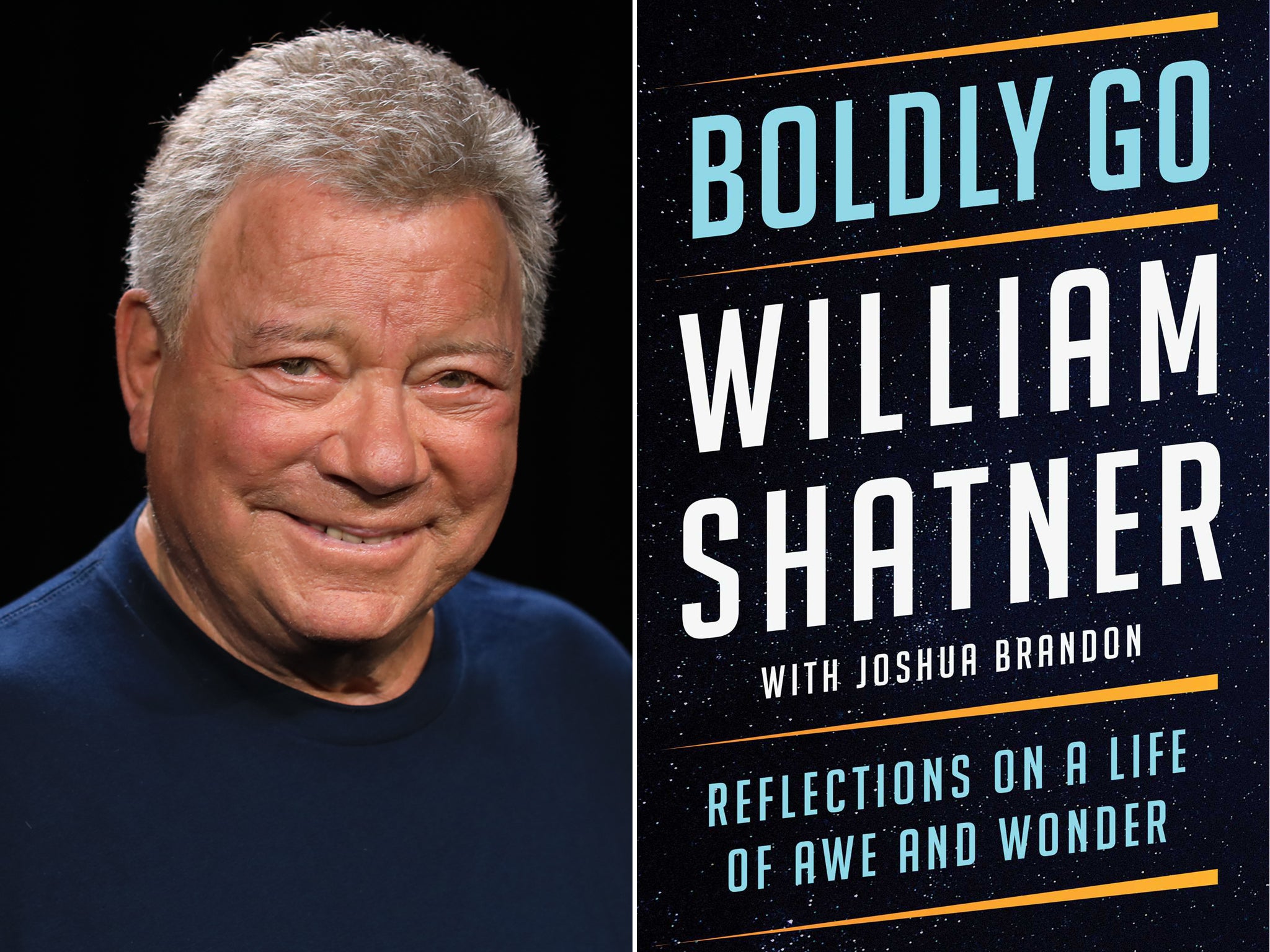

Boldly Go: Reflections on a Life of Awe and Wonder by William Shatner

★★★☆☆

After four wives, 72 movies and 124 television shows, 91-year-old William Shatner has released his latest memoir, Boldly Go: Reflections on a Life of Awe and Wonder.

You get the sense that ghost writer Joshua Brandon simply let the tape recorder run and then did his best to pull together a sweet read. There is certainly a rambling senior charm to Shatner’s tales of his daredevil exploits, his money problems (the fact that there were “no residuals” from Star Trek is mentioned more than once), his tinnitus and his regret at killing a bear while hunting. There are also copious philosophical reflections on grief and loss, the damage humans have done to the planet and the importance of our shared connections to “the fabric of Earth”.

Shatner shows us the “existential struggles” of a tortured soul – “I have been very lonely at times,” he admits – and he also seems keen to come across as a benign and cuddly old soul. And yet. The man who found global fame as Captain James T. Kirk confesses he fell out badly with Leonard Nimoy (Spock), admits he “did not reconcile” with James Doohan (Scotty) and that George Takei (Sulu) “still feels sore about our association”. Shatner recalls interviewing the late Nichelle Nichols (Uhura) for his book Star Trek Memories, and admits: “I was dismayed to hear her tell me that she and a few of the other cast members quite disliked me while we were making the series. In their eyes, I had been cold and arrogant.”

Although the bits of padding (well-worn “famous actor anecdotes”) wear a bit thin, the book is capable of surprises, including the enlightening tale of the “ugly” atmosphere when Shatner was shooting an anti-racism film called The Intruder in East Prairie, Missouri, in 1962. The film was made when Shatner was in the early stages of his career and filmed during an era of segregation. Unbeknownst to the film crew at the time, a lot of the extras had taken part in a lynching at the site of filming in the 1940s.

The book will undoubtedly appeal to Star Trek devotees, and it will also touch the hearts of animal lovers. There are copious stories about dogs and horses. Shatner recalls befriending a wild street dog as a child and when it was killed by a car, he was overwhelmed. “To this day, I am affected by the memory of losing that dog. It was almost eighty years ago.” Who said that life was logical?

Boldly Go: Reflections on a Life of Awe and Wonder by William Shatner with Joshua Brandon is published by Simon & Schuster on 10 November, £20

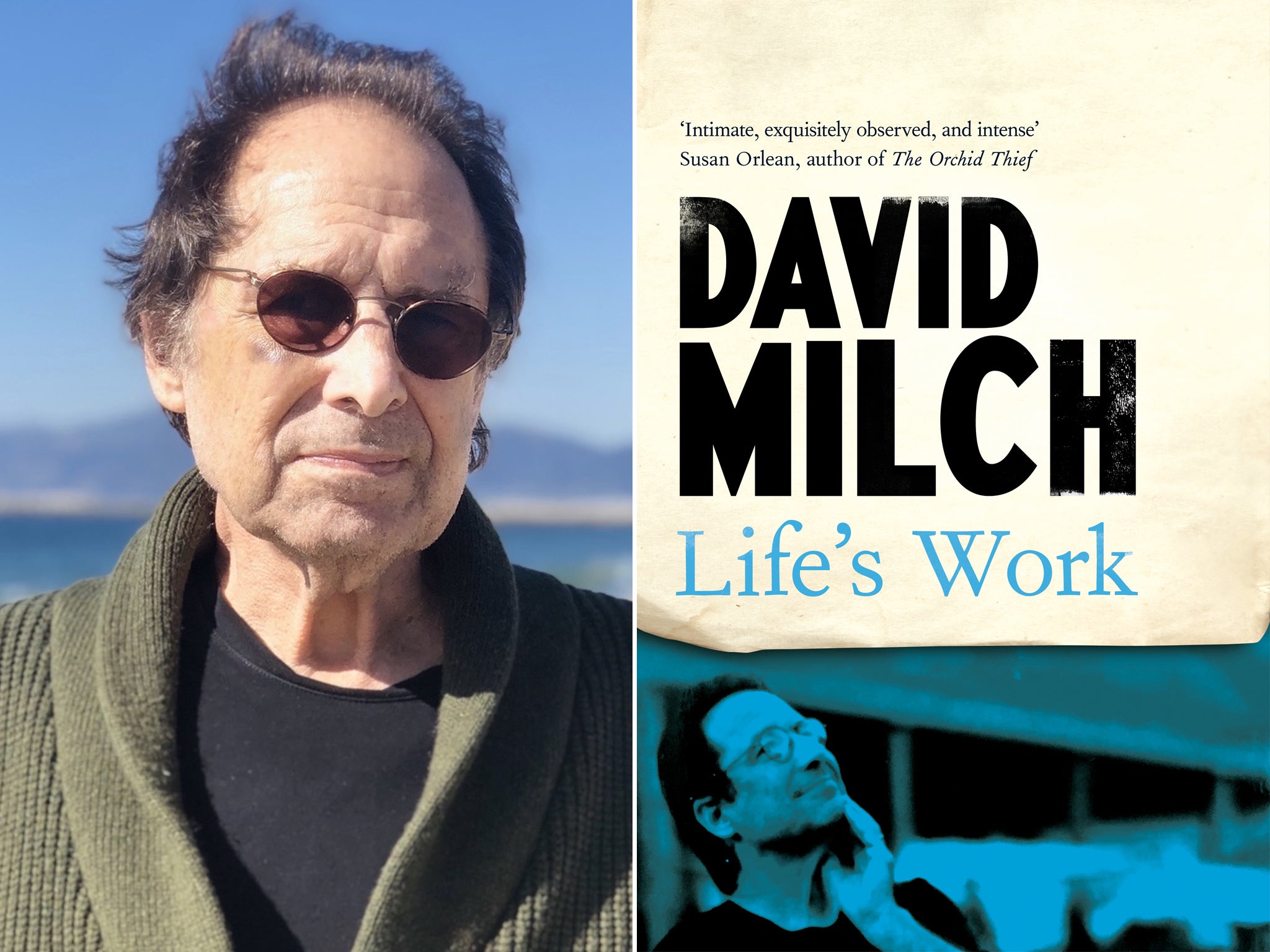

Life’s Work by David Milch

★★★★☆

David Milch is responsible for creating and writing two of the best television series of modern times in NYPD Blue and Deadwood, and he was also a key writer on the trailblazing cop show Hill Street Blues, where he came up with the famous sergeant’s line, “let’s do it to them before they do it to us”. Milch, who was diagnosed with dementia in January 2015 at the age of 71, has, along with help from his children, used years of taped memories and script notes to pull together a searing, brutally honest memoir.

His father was a compulsive, depressive alcoholic, who took his life in front of his wife and Milch’s elder brother Bob. Milch used his father, in part, as the model for detective Andy Sipowicz in NYPD Blue (also drawing on the experiences of a helpful New York cop called Bill Clark to help actor Dennis Franz) and Milch, himself a compulsive boozer, makes an interesting point about drinkers. “My dad was so self-enclosed. Alcoholics in particular are like that, everything’s got to be exactly the same,” he says.

Milch also drew on his own horrific experience of being sexually abused at summer camp for a brilliant episode of NYPD Blue in which the detectives are trying to convict a predator. “I became closely acquainted with profound feelings of guilt and shame,” says Milch of his own trauma.

Along with some thought-provoking reflections on existence itself, Milch also opens a window on unusual aspects of life. When he was writing Jimmy Smits’s NYPD exit using a terminal illness plotline for his character Bobby Simone, Milch called on his brother, a leading palliative care doctor, for advice on the script. Milch writes, almost in passing, that when his brother was building a hospice in Buffalo “he had them design it as a circle, so pacing family members could never get lost”. It’s an image to stop you in your tracks.

During a hugely successful screenwriting career, Milch was often “loaded and losing my mind”, high on drugs and acting wildly (there is a crazy story about wrecking a family car) and his gambling and impulsive racehorse buying stored up disaster. Milch eventually had to admit to his long-suffering wife Rita that he was about 17 million dollars in debt, after bad bets, unpaid taxes and business losses. Yet Milch is never self-pitying or self-excusing. “Sometimes hating yourself is a fair response to the data,” he notes.

Milch, who was mentored by poet Robert Penn Warren, is undoubtedly a divisive character. He recalled of his time at Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1967, that, “Kurt Vonnegut and Richard Yates were teaching there and they both hated me.”

Despite having major heart surgery at 47, Milch went on to create and write HBO’s Deadwood. The sections on that series, and 2019’s Deadwood: The Movie, are particularly engrossing, including his memories of how the show started as a Roman epic, how it evolved to be based on real events from the western Gold Rush, why it was written in iambic pentameter, how the characters developed and what it was like working with complex actors such as Brian Cox, Ian McShane, Tim Olyphant and Robin Weigert. He also details his work on HBO’s Luck and his fallout with director Michael Mann.

It is clear that Milch has a remarkably sharp eye for the grotesque and the bizarrely comic. That is all summed up in his tale of talking to an “extra” while working out a scene for the Deadwood episode “Amateur Night”, in which Cox’s troupe hold a talent night for the people in the camp. Milch stopped a small, bowlegged “extra” and asked him if he had any special skills. “I can cry at will,” said the man. “Now we’ve got a game,” Milch replied, giving him a special part in the episode.

Life’s Work by David Milch is published by Picador on 24 November, £20

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments