The Indy Book Club: Convenience Store Woman is a gothic love story with a sickly capitalist kink

The fourth pick of our fortnightly book club explores the eerie thrill of disappearing into nothing through work, writes Annie Lord

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Keiko Furukura describes the Hiiromachi Station Smile Mart she’s worked at for 18 years as though it were her boyfriend. She tells of how the whirring of the freezers and the beeping of the coffee machine “ceaselessly caress my eardrums”. And when alone at night in her small, pokey flat, she dreams so much of “the brightly lit and bustling store” that she begins to shape herself to please it: “I silently stroke my right hand, its nails neatly trimmed in order to better work the buttons on the cash register.”

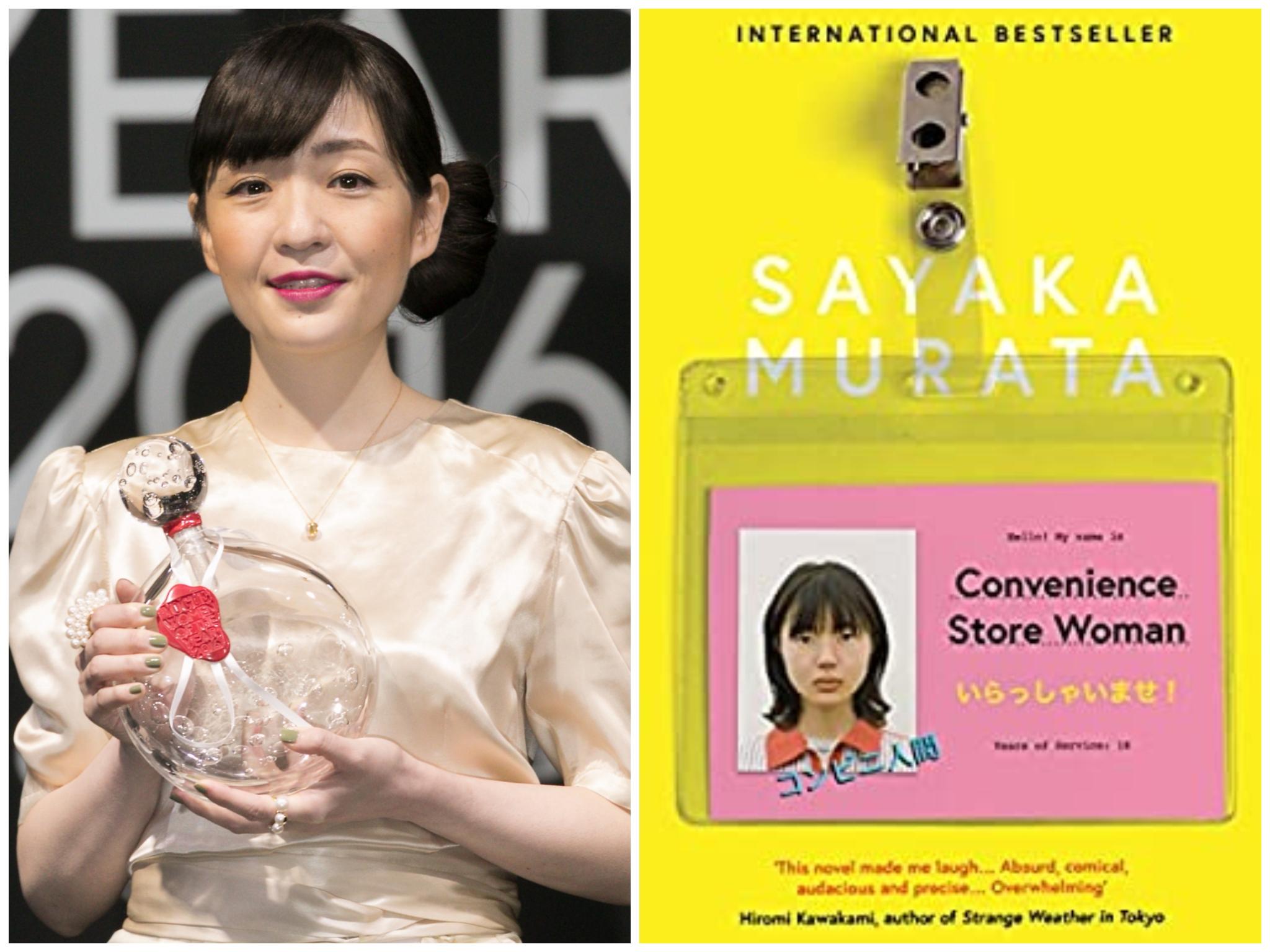

Keiko is the emotionally detached star of Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman, which in 2016 with the help of Ginny Tapley Takemori became the first of her 10 Japanese novels to be translated into English. Prior to getting hired at the Smile Mart aged 18, Keiko was a societal outcast who lived life in such utilitarian terms that she often horrified those around her. When as a kid she found a pretty bird dead in the school playground, her first instinct was to grill it for dinner. As a teacher struggled to break up a fight between two students, Keiko whacked one of them over the head with a spade, so hard there was blood. She gets older and fantasises about silencing her sister’s wailing baby with the small knife they just used for slicing birthday cake. “If it was just a matter of making him quiet, it would be easy enough.”

It is only in the “transparent glass box” of the convenience store that she finds acceptance and purpose. On her first day, Keiko receives a uniform and a manual that prescribes her behaviour right down to the scripted interactions she must have with customers. “Certainly. Right away, sir!” she chimes. “Thank you for your custom!” She finds fulfilment in the easy rhythmic chugging of daily tasks. Stacking fizzy drink cans high. Pushing the sale of mango-chocolate buns because they are on offer. Making more croquettes than usual because people prefer them when they’ve gone cold. The whoosh and thump of the fridge doors slamming under her fingertips. The glint of the light on the floor she’s shined. She believes she can “hear the store’s voice telling me what it wanted, how it wanted to be. I understood it perfectly.”

Through her work, Keiko is able to ape the actions of a normal person and thus assimilate into a society she had hitherto been pushed out of. “I felt reassured by the expression on Mrs Izumi and Sugawara’s faces,” she says after mirroring their anger at another employees’ failure to restock shelves properly. “Good, I pulled off being a ‘person’. I’d felt similarly reassured any number of times here in the convenience store”.

She is so good at her job, devoting herself so wholly to its demands, that any self that exists outside of work begins to slip away into nothing. Keiko becomes like an electronic arm on a machine, picking up and putting down when it’s buttons are pressed. “I automatically read the customer’s minutest movements and gaze, and my body acts reflexively in response,” Keiko thinks, as she predicts from the motion of a shopper’s hand that he will pay on card.

While initially Keiko goes to the Smile Mart in order to fit in, as she reaches 36, her family worry about her lack of prospects. Staying there starts to seem like an act of defiance. Worried about the fate of her work, Keiko takes useless shop worker Shiraha home with her, hoping that having a fake boyfriend might get everyone to leave her alone. He’s a greasy, lazy slob who says things that wouldn’t sound out of place on an incel Reddit thread. “The youngest, prettiest girls in the village go to the strongest hunters,” he says, reeling off another Jordan Peterson For Dummies-style theory. “They leave strong genes, while the rest of us just have to console ourselves with what’s left.” Feeding off her finances like a tapeworm, Shiraha eventually convinces Keiko to quit her job for a better paid one and it’s a breakup which leaves her devastated.

Convenience Store Woman is a gothic love story for our times, not with a vampire, a ghost or a zombie, but with those temples of consumption that glow on the edges of street corners, promising short queues and reliable products. It’s capitalism kink and it makes readers anxious. How easily we are charmed by the allure of efficiency. The smooth running of the machine. Productivity distilled to its most concrete essence. But it’s not a manifesto, so Furukura withholds judgement and gives us permission to enjoy the love story from the bottom of its Plasticine pink heart. At least that’s something you can’t buy.

Here’s what some of our readers thought...

May, 34, Leeds

So much of the time, in life, we are taught to want more, but in seeking it often you only get less. I work in marketing, which is supposed to be a “good job”, but often I miss the calm regularity of my days working in the supermarket. The coronavirus has highlighted our reliance on key workers such as shop staff. When I worked there, I didn’t have any anxiety that what I was doing was useless. I feel useless often in my office job. Keiko knows the importance of what she does.

Emily, 22, London

Keiko is meant to be the weird one but as the novel progresses, you realise it is more everyone around her who is odd. Why are they so obsessed that she get a better job when she is happy? Why does she need a boyfriend or a baby? The only thing I think is a bit disappointing is that this critique of society is channelled through a character whose inability to relate to others ordinarily would be read as autistic. You don’t have to have a developmental disorder to think that our fixation on career, marriage, childbirth is strange. I do too!

Matt, 45, Newcastle

Often when we work, we become not human. People don’t see you when you’re in a uniform. You speak in a way that’s more like a robot than a person. Sometimes it’s relaxing – it takes you out of the anxieties of wanting “more”, that you should make a podcast, get a new outfit. But another kind of work is possible, one where Keiko could gain pleasure not because she’s erased but because she’s allowed to become more herself.

Our next Indy Book Club pick will be voted for by you. Send your thoughts to annie.lord@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments