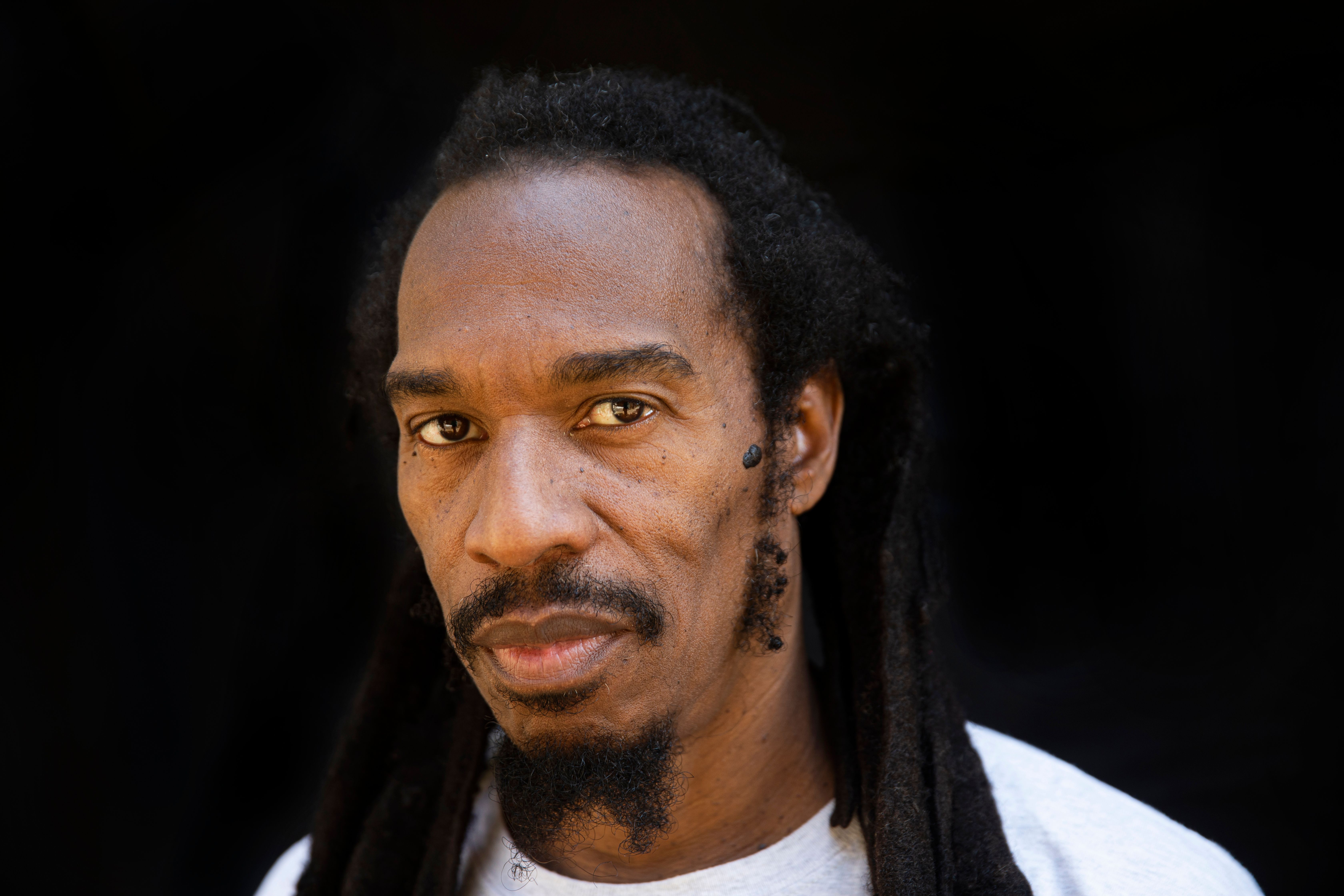

I met Benjamin Zephaniah several times – he was as open and kind-hearted as his poetry

Helen Brown interviewed the poet and writer on many occasions before his death. Here, she speaks about what made him so special, both to herself and her autistic son on whom his poetry had such a profound effect

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Be nice to yu turkeys dis christmas,” wrote Benjamin Zephaniah in a poem I know he’d be proud to learn made vegetarians out of hundreds of children across the UK. I say “wrote” but really, because of his extraordinarily warm readings, I bet more kids heard that line read aloud than read it themselves. Teachers pouncing on the chance to sell a poet who didn’t look or sound like a clichéd bard. “Look, kids!” I picture them saying. “Ben’s Black! He’s from Birmingham! He’s funny!” Today, heartbreakingly, he’s become one of the things kids do expect poets to be: dead.

According to most reports, Zephaniah was diagnosed with a brain tumour eight weeks ago, which is what seems to have killed him at age 65 . I think he’d thank me for not euphemising things. In a poem about the media, he asked readers: “How do you like your truth?/ Bite-sized in sound bites cut easy to chew, With a talking head saying the victim’s like you/ And when you’ve digested the horrors you’ve seen/ You find good, you find evil, and no in-between…” No. Zephaniah liked things clear. So, there: he’s dead.

Having interviewed Zephaniah on several occasions, I can hardly process the idea of such a gentle, joyful lifeforce lost so soon. I often approach interviews with anxiety, knowing that I will have to ask personal – some might say invasive – questions. It’s hard, but Zephaniah made it easy. “You know I’m infertile?” he said to me within minutes of our first meeting. Soon he was telling me about the deep sorrow that came with the knowledge he’d never have kids of his own, speaking about how that affected his relationships with women, asking for my input, and gently pushing the conversation into the nooks and crannies of possible hope and failure. As a journalist, I was young and felt out of my depth.

Walking back to the train station afterwards, I felt as though this weight of huge subject matter had passed through me at great speed. But when I got home and listened back on my dictaphone, I was reminded that Zephaniah had spoken slowly, slower than most interviewees, and in easy-flowing language. I heard the soft space around our exchange, and heard it harden as I got on with my job, questioning him on the blunt facts of his past.

The son of a Barbadian postman and a Jamaican nurse, Zephaniah was born in Birmingham in 1958. Dyslexia cut him adrift from regular education. “I remember a teacher talking about Africa and the ‘local savages’,” he told The Guardian in 2015, “and I would say, ‘Who are you to talk about savages?’ She would say, ‘How dare you challenge me?’ – and that would get me into trouble. Once, when I was finding it difficult to engage with writing and had asked for some help, a teacher said, ‘It’s all right. We can’t all be intelligent, but you’ll end up being a good sportsperson, so why don’t you go outside and play some football?’ I thought, ‘Oh great.’ but now I realise he was stereotyping me.”

Zephaniah knew he had poems in “his head even then”. When he was 10 or 11, his sister began writing them down for him. “When I was 13, I could read very basically but it would be such hard work that I would give up,” he said. “I thought that so long as you could read how much the banknote was worth, you knew enough, or you could ask a mate…”

His struggle to make sense of written language formed a powerful plank in the work he’d go on to create. My own son is autistic and was slow to learn how to read and write, despite him being very clever. I will always remember the day I realised my child had learned to laugh at the adults who patronised him; I had found him holding a book of Zephaniah’s poetry, reading a poem called “Sunny Side Up”. That particular poem is presented in the book upside down, designed to mess with the system. It runs: “When people/ See people/ reading up/ Side down/ They think/ Maybe,/ The reader/ Can’t read/ But/ You should/ Smile now/ Because you/ Have found/ A poem/ That’s out/ To mislead.” My son must have known that poem by heart in minutes, but he loved holding the book, carrying it with him on public transport. After a day of being told he was less than his peers, he relished Zephaniah’s anointment of intelligence.

“Sunny Side Up” shifted the entire power dynamic between my autistic son and his teachers; it gave him the confidence to read on. It’s one of many Zephaniah poems that showed kids how to be smarter than their adult teachers. What we now call “critical thinking” came for free in his books.

Zephaniah famously made his way out of crime. In his early life, he was busted for a youthful burglary and cracked on. He challenged racial stereotypes. He refused to conform to binary positions on anything. When it came to Brexit he felt that, “For left-wing reasons, I think we should leave the EU but the way that we’re leaving is completely wrong.”

It is for his animal rights campaigning, though, that Zephaniah will be most dearly remembered. He became a vegetarian at nine and a vegan at 13. Last year, he told The Guardian that his decision had roots in how he was treated at school. “I experienced racism in and out of the classroom, so in the playground I would often find myself sitting in a corner talking to the local cats. When the cats were away, I’d talk to the birds and the bees. Amazingly, I never met a racist animal,” he said. “Some were nervous when they first approached me, some would make a few visits before they got close, but it never took long for us to make a connection. Then we would just hang out together.”

Zephaniah’s sly environmentalism had a profound effect. I can clearly recall my daughter running home from primary school on the day they’d played Zephaniah’s “Talking Turkeys” poem, yelling, “MUM! YOU WERE RIGHT!” It goes: “Be nice to yu turkeys dis christmas/ Don’t eat it, keep it alive/ It could be yu mate, an not on your plate/ Say, Yo! Turkey I’m on your side.”

Thing is, if you talked to him, Zephaniah would find a way to make you feel as though you were on the same side. He did it by listening. He did it by loving. You could hear it in his rich, low, and kindly voice. Remember Zephaniah by not eating turkey. Because, as he said: “Turkeys are cool, turkeys are wicked/ An every turkey has a Mum.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments