Arifa Akbar's Week in Books: The joy of letters, from chatty to catty, in old and new forms

The form has changed but the impulses remain the same. The quickening of the heart can lie in an inbox too

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“This is the night mail crossing the Border,/ Bringing the cheque and the postal order,/ Letters for the rich, letters for the poor,/ The shop at the corner, the girl next door.”

So begins WH Auden’s “Night Mail” on the thrill of receiving letters. But does the modern-day equivalent of his steam train still tremble its nocturnal journey across our landscapes? Do we receive Auden’s “the chatty, the catty, the boring, the adoring/ the cold and official and the heart’s outpouring” through the post, or is the letter sharing its fate with the mail train, parked in perpetual retirement in a museum?

When was the last time you received a proper letter through the letterbox, or sat down to write one yourself, on coloured Conqueror paper? A long time ago, I suspect, though there has been a concerted effort to reinsert the handwritten letter back into cultural life lately.

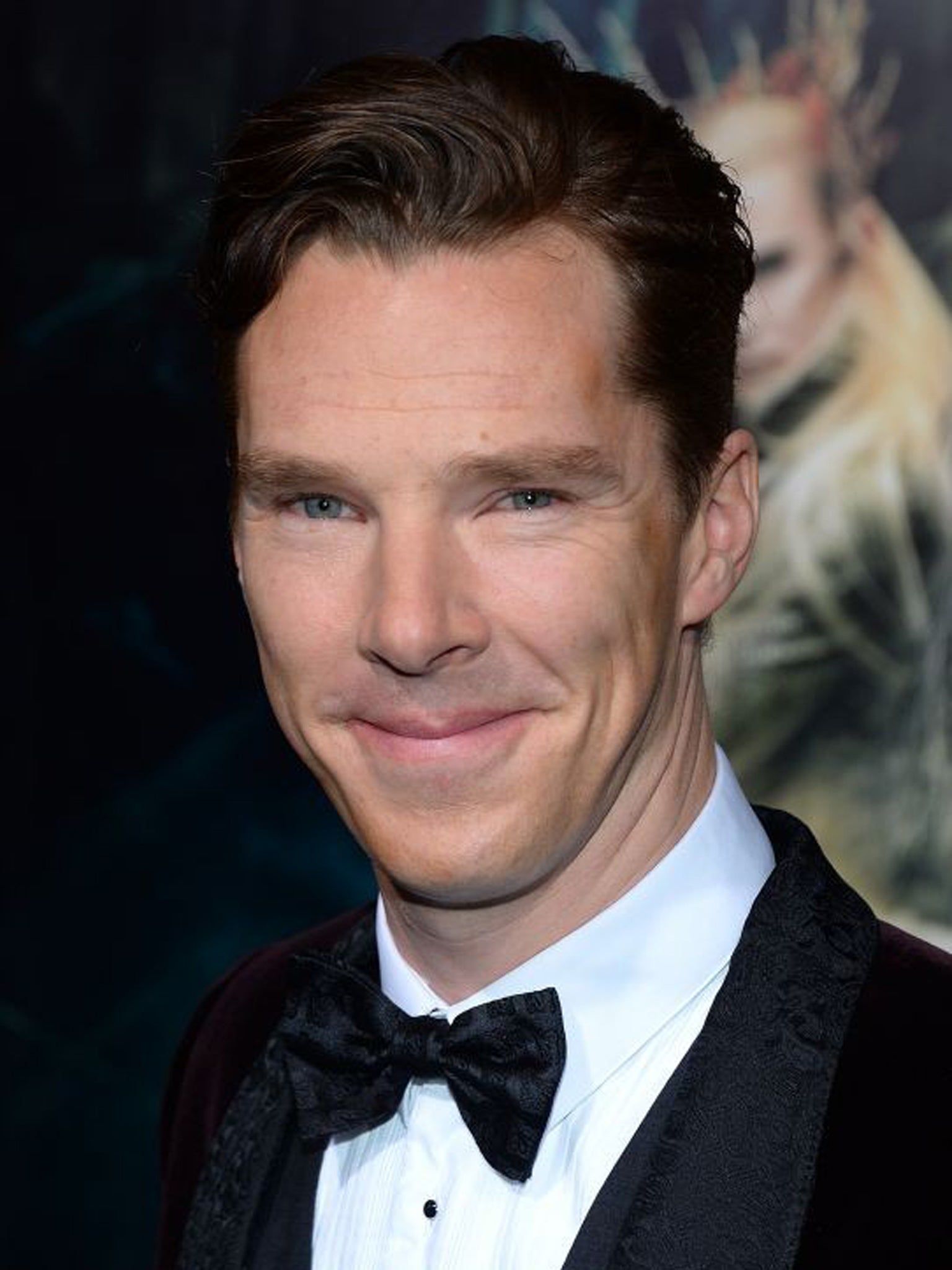

This week, Canongate organised an evening in which people of note read letters of note out aloud to an audience in West London. It was an extraordinary event: Gillian Anderson read Katharine Hepburn’s tender letter to Spencer Tracy, penned a decade after his death as an ode to her former lover; Juliet Stevenson made us gulp down tears with Virginia Woolf’s last letter to her husband Leonard – possibly the most loving suicide note ever to be published (“You have given me the greatest possible happiness”); Nick Cave, DBC Pierre and Neil Gaiman added to the laughter and tears with their selected epistles. Best of all was Benedict Cumberbatch and Kerry Fox’s readings of the volley of letters between Chris Barker and Bessie Moore, two postal workers who fell in love through wartime letters to each other.

The Canongate event must have been the biggest celebrity endorsement of the humble epistle that I have seen. I’m told it will be followed by similar celebrations next year, including one in Queen Elizabeth Hall. Yet, despite the mirth of the night, there is dewy-eyed nostalgia around the conversation on letters. Although the effort to “save the letter” is full steam ahead – the celebrities, a spate of recent books including Simon Garfield’s excellent To the Letter – it seems as if we have agreed that the fight is lost, and the evil email has risen victorious.

I don’t think it is an either/or equation. Hand-written letters will always exist because unique occasions require them. It would be pretty unusual to receive a typed suicide note, or condolence letter, or even a love letter, though some of us have – disturbingly – received the latter. These instances demand a physical humanity, “a piece of yourself”, as Bessie tells Chris, and this can’t be imparted in print – not with the same emotional impact. We must also resist the urge to romanticise the old form, and denigrate the new. To pit the email against the letter is misguided (for those who do). After all, Edwardian letters resembled emails –mini messages sent many times a day and written in haste.

Auden notes that “none will hear the postman’s knock/ Without a quickening of the heart,/ For who can bear to feel himself forgotten?” Well, this quickening of the heart lies in an inbox too. The form has changed but the feelings and impulses to express them remain the same.

People still meet and fall in love in “letters” like Chris and Bessie, though now it happens on online dating sites. Electronic correspondence need not superannuate the written letter, just as an e-reader does not render the physical book redundant. There is a place for both, and each have their unique charms. To hand-write a letter is to dedicate your thoughts to a particular person but, unlike email, you can’t cut and paste and edit yourself unless you write a rough draft first, which seems a bit much. That is perhaps why letters can sound rambling and off-course and this is their own particular charm.

The other curious part of the process is that they comprise a jigsaw between two people – and this jigsaw is never whole, or at least, not while the two parties are alive. In some ways, it is as interesting to read one side of a correspondence – those sent to Lord Byron by his lusty female fans, for instance – as the reconstituted pairings, such as in the book of letters between Christopher Isherwood and his lover, Don Bachardy, or that of the Freuds on page 21. A neighbour told me she has letters sent to her late mother by her late father from the front line during the Second World War, but has none of her replies. They’d make for an elliptical love story.

This ellipsis would never occur with emails. We have shadow copies of everything. In some ways, it makes the e-archiving of literary correspondence – Wendy Cope’s at the British Library, Salmon Rushdie’s at Emory University– even more comprehensive, but, then, the challenge is in the accessibility of so much information – so many emails – existing in disembodied form.

Sachs on Fawlty Towers, Kristallnacht – and hopefully not much on ‘Sachsgate’

“Manuel” is writing his autobiography. Or Andrew Sachs, I should say, the actor who gave us the famously ditzy Spanish waiter from Fawlty Towers. It will be published in February and will tell of a boyhood in war-torn Berlin where he witnessed his father being arrested by Nazis, his escape to England where he had to learn everything anew, and his work with Rex Harrison and Richard Burton, among others. I do hope that his take on one puerile phone call from Russell Brand and Jonathan Ross doesn’t overshadow what sounds like an otherwise genuinely interesting story.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments