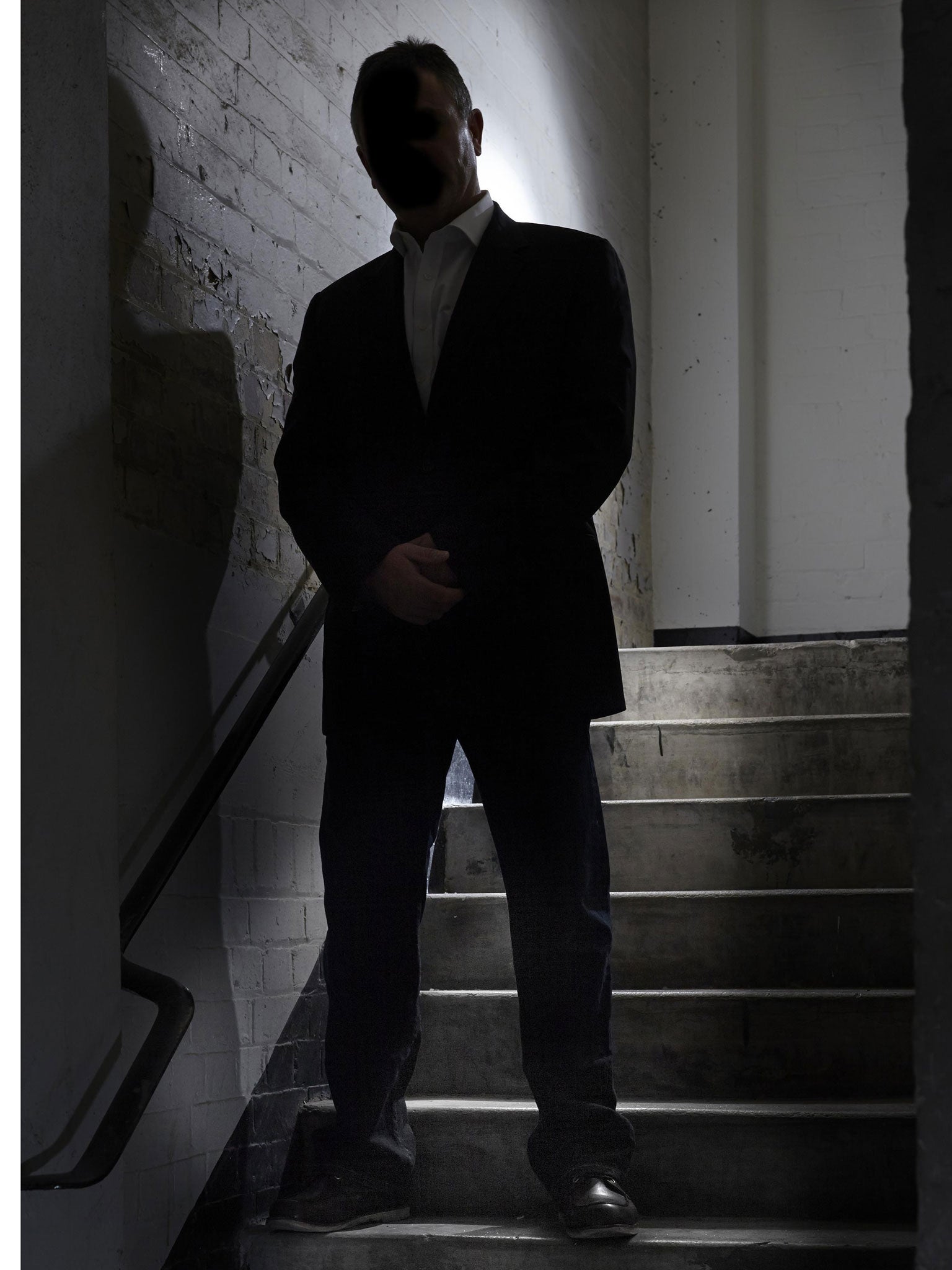

Andy McNab: 'Janet and John changed my life'

When Andy McNab joined the Army, he had a reading age of 11. Here, he describes his literary epiphany, and how it now informs his teen fiction

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I suppose I didn't have the most conventional start in life, although a lot of people have it much worse. I was a foundling, left in a carrier bag outside a London hospital as a newborn baby. My adopted parents did their best, but life was tough where I grew up, in Bermondsey in south London, and money was always tight.

As I got older, the disillusionment set in. I didn't want to be the kid in the free school dinners queue, or the one with the free bus pass. I felt angry with people who had shiny new cars or motorbikes. I vandalised people's shops and houses simply because they had stuff and I didn't. I can also remember being very angry with my schoolteachers. I had gone to seven different schools, so I had a lot of teachers to be angry with. I was angry that they kept putting me in remedial classes, but I didn't exactly do anything to get out of them. In fact, I used to like being at the bottom. It gave me yet another reason to feel angry. I liked the feeling of being a minority and that everyone was against me. It justified my anger, which entitled me to do things that others couldn't or shouldn't do.

By the time I was 16, I was in juvenile detention for breaking and entering. And as far as I was concerned, this was everyone else's fault. If no one cared about me, why should I care about myself?

Then one morning the Army turned up at the detention centre. They showed us a recruitment film featuring a little two-seater helicopter and a pilot wearing a pair of shorts and a T-shirt as he flew really low over the beaches of Cyprus. He was waving down at the girls, and they were waving up at him. Not surprisingly, I signed up there and then, and got my ticket out of detention. Soon after arriving at the Army training base in Kent, I discovered that I was functionally illiterate – meaning that I could not handle much more than straightforward questions and had no understanding of allusion or irony. My literacy levels were those of an average 11-year-old's. The dream of being a helicopter pilot ended there and then, and I joined the infantry.

It was a few weeks later that we were marched into what I found out was the Army education centre. What happened to me that day changed my life. I read my first book – one from the Janet and John series aimed at primary children – and the educator said to me: "Remember the feeling of closing your first book, because you are going to find out that reading gives you knowledge, which gives you the power to make your own decisions and to do what you want to do."

For the first time in my life, I could see a different future ahead. I kept reading and I kept learning and feeling that I was in control of where I was going. Reading The Sun was a lot easier. I used to buy it for page three and for the football – page three was easy enough, not too many words to worry about, but the back pages were difficult and I would miss whole parts of sentences. I found that reading gave me a sense of pride in the fact that I wasn't thick. I'd never had that feeling before.

As I went on through my Army career, both in the Royal Green Jackets and later in the Special Air Service, my education progressed. You could be the best soldier on the planet – the hardest and the fittest – but if you didn't earn academic qualifications then you weren't going anywhere.

When I was approached to write Bravo Two Zero, my first book, I was given a copy of Touching the Void by the mountaineer Joe Simpson. What I learnt about writing from that book was the importance of texture – how did the desert feel and smell at night, when the temperature suddenly dropped and we were all freezing cold? Was I scared when I was captured in a drainage ditch near the Syrian border? What were my feelings towards my captors?

I later learnt another valuable lesson, this time from the Hollywood director Michael Mann.I guess it was obvious to him that I had come to reading late in life, and he suggested that I view a book as a TV show and think about the action visually, adding in the rest later. This technique worked for me. The opening chapter sets the scene; the chapter endings are the ad breaks. And finish with a conclusion that isn't too long; get out before people get bored.

It was remembering that feeling of elation that I had when I closed my first book which led me to write my latest young adult book, The New Recruit, in collaboration with a group of young Soldiers Under Training at the Army Foundation College. The average literacy age of an infantry recruit is still 11, and the Army plays an important role in getting these lads reading and writing. I wanted to give them that same feeling that I had all those years ago, and so I spent several days up at the college, doing workshops with the lads, talking about their experiences, about why they joined up and what their hopes for the future were, and got them to write it all down – and to keep writing. If it makes a difference to just one of these young men, then it will have been worth it.

Now I talk to soldiers, schoolchildren, young offender institutions, prisons and work places, in my role as the Reading Agency's Ambassador for the Six Book Challenge. The Six Book Challenge invites people to choose six reads (poetry, magazines and articles, as well as books) and record their reading in a diary to get a certificate. The idea is to get people back into the habit of enjoying reading. Whether they are reluctant kids or embarrassed adults, reading has the power to change everyone's lives, and the message that I try to give to them is that if I can do it, anyone can.

That doesn't mean to say I know it all. I don't, and nor does anyone else. I'm not embarrassed to ask questions and I am still learning.

More details of the Six Book Challenge can be found at readingagency.org.uk

The New Recruit by Andy McNab

Doubleday £9.99

"Not 50 metres in front of him, Liam saw movement. Most times it was just a stray goat or some other straggly creature trying to find something to eat amongst the dry scrub and brush of Afghanistan, but to Liam's now well-trained eye, it was something more. Human for sure. And from the way it was moving, it was no shepherd. Not unless this one had taken up crawling on his belly to gather his flock ..."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments