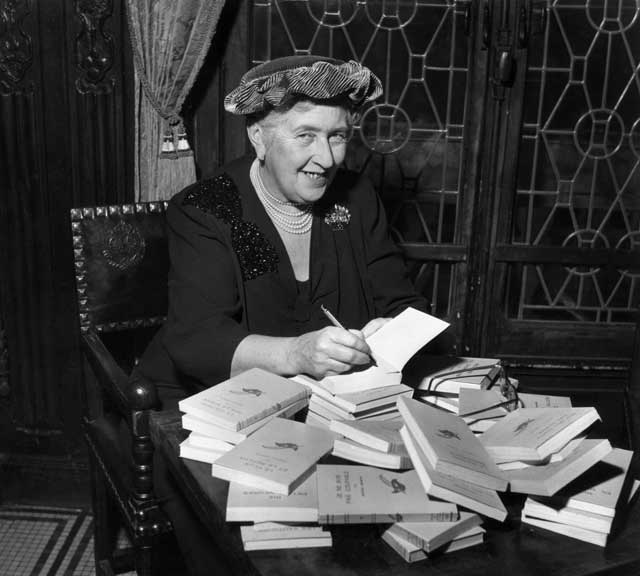

Agatha Christie: The curious case of the cosy queen

No enemy can murder Agatha Christie. From India to France, her mysteries sell by the million. As crime buffs gather in Harrogate to investigate her lasting appeal, Andrew Taylor presents his defence

We know whodunnit but not how. The curious case of Agatha Christie remains the great unsolved mystery of crime fiction. It is relatively easy to understand why we continue to read the work of Edgar Allan Poe or Arthur Conan Doyle, or for that matter Wilkie Collins, Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. Nor is it difficult to explain their enduring influence on the genre.

But Christie? How does she do it? And, in the process, how has a shy, upper-middle class lady, born in Torquay in 1890, become (almost certainly) the most widely read novelist in the world today?

She really is the odd one out among these influential crime writers - and not just because she is the only woman among them. For a start, so many people go out of their way to make clear their dislike of her work.

Broadly speaking, her detractors fall into two camps. On the one hand, Christie has to contend with the sneers of the critics. The classic example is Edmund Wilson's essay "Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd", one of his three diatribes against detective fiction that appeared in the New Yorker during the 1940s. He concludes that Agatha Christie's work is sub-literary, best considered as something between a trivial pursuit and a mildly shameful addiction.

Christie's work has also been attacked from within. Like anything else, crime fiction has its fashions. Raymond Chandler's 1944 essay, "The Simple Art of Murder", savaged the Golden Age whodunnit and its practitioners, including Christie, and praised the more realistic American pulp school of crime writing exemplified by Hammett.

Nowadays, within the genre, the currently fashionable taste is for noir - gritty and morally ambiguous stories set in the big city, whose authors aspire to tick sociological and even ethical checkboxes as well as literary ones. You rarely find someone confessing their admiration, untinged by irony, for Christie on Front Row.

For both critics and devotees, her name conjures up "Mayhem Parva" - a Home Counties village with respectful rustics and a host of middle- and upper-class characters. This enclosed, idyllic world is disturbed by a murder. There is a host of suspects, most of whom either employ servants or (in the later novels) used to do so.

The reader is invited to pit his or her wits against those of the detective, who eventually brings the case to a dramatic and unexpected denouement. The story ends at this point, so the reader rarely has to cope with the messy procedures of evidence-gathering, trial and punishment. We know without being told that one of those invaluable servants will manage to remove the bloodstain from the drawing-room carpet.

On the face of it, the formula seems to have little to do with either crime or literature. It seems narrow and mechanical, and likely to produce dull and repetitive results. So Christie's books are unreal, unfashionable, unliterary and often, by modern standards, downright snobbish. In that case, why are they so widely read?

For this is the second reason that Agatha Christie stands out among her peers. Despite the various attacks on it, her work has been, and continues to be, quite staggeringly popular. Conan Doyle himself cannot match her record or even come near it.

The statistics tell their own story. Chorion, the entertainments and leisure company that now controls Christie's copyrights, along with those of Blyton, Chandler and Simenon, reckons that Christie's books have sold more than 2 billion copies worldwide. Each time they are rejacketed - in the UK, that's about every six years - there is a surge in sales as new readers are lured to her books, and old ones rediscover them.

Today, HarperCollins, her publisher since 1926, sells a million copies a year in every country in the world where English books are sold (apart from the US, where Christie has another publisher). Christie sales have actually grown by around 50 per cent over the last ten years, completely contrary to the trend. She's now one of the top five authors in India. According to UNESCO figures, she is the world's second most translated author. The top place, incidentally, is occupied by a team of Walt Disney writers; Shakespeare comes in at number four. It's impossible to find a single reason for this continuing popularity. But several factors have undoubtedly contributed to it.

In the first place, there are the qualities that Christie shares with many other authors of traditional whodunnits. Most obviously, some of the appeal must derive from the simple fact that death is universal, and so is the deep-seated unease that murder creates; and so is the love of puzzles that have solutions.

WH Auden, a self-confessed addict of detective fiction, argued in a brief but influential essay, "The Guilty Vicarage", that the charm of the genre has nothing to do with literature: it is essentially magical, and its effect is cathartic. A whodunnit gives Genesis a happy ending: it introduces a serpent into Eden but concludes with its expulsion, leaving Adam and Eve to enjoy their restored innocence.

Put another way, the traditional whodunnit in the Christie mould works as a sort of literary analgesic. It shows us, in safely fictional terms, what we most fear, and then creates the illusion that human reason can both understand it and resolve it. So Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple fulfil functions that combine those of the shaman and the scientist.

True or not, this theory fails to explain why Agatha Christie should have done so much better than her rivals. Christie's first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, came out in 1920 and earned her £25 from her grasping publisher. But this and the novels that followed rapidly created a market for her work not only in this country but abroad. Despite their localised settings (literally parochial in many cases), despite the social attitudes they enshrine, her stories work well in other languages and cultures.

Her prose is plain, direct and effective, which makes it easy to translate. It will give pleasure even to unsophisticated readers. It's no accident that a Christie whodunnit is often the first "adult" novel that a child reads.

Similarly, the characterisation is equally straightforward. Her critics do not see this as a virtue. But it makes her characters very accessible, for the detail is so spare, and often so generalised, that readers can interpret them in their own way.

Christie's popularity also has much to with the versatility of her stories. It became clear at a very early stage that her characters and storylines could be transferred to other media. The first film of her work is a German adaptation of The Secret Adversary (Die Abenteuer GMBH), which appeared as early as 1928. There's an irrelevant but deliciously surreal story that the master reel for the film was found inside the Berlin Wall when it was pulled down.

Chorion estimates that there have been about 190 film and TV adaptations of Christie's work worldwide. The best of them – Joan Hickson's Miss Marple, for example, or David Suchet's Poirot – pay Agatha Christie the supreme compliment of aspiring to be as true as possible to the spirit of the original novels. It is no surprise that they tend to be among the most commercially successful of the adaptations. Viewers, like readers, prefer to suspend their disbelief for the duration.

Christie's stories work equally well as radio adaptations or as audiobooks. The record-breaking West End run of The Mousetrap still testifies to her skill as a dramatist. There are Christie e-books and interactive games. In France, where she is the best-selling author of all time, her work is appearing as a series of graphic novels. Her stories are like water: they fit the shape of the container that holds them.

As a crime writer, Christie's talents have much in common with those of the conjurer and the stand-up comic. She is the queen of carefully controlled narrative. Her skill as misdirecting the reader amounts at times to genius. She distracts our attention at the crucial moment; she toys with our stock responses. Her puzzles are rarely dull and over-complex - unlike those of Dorothy L Sayers and many other Golden Age crime writers. The best ofthem not only fool the reader but, afterwards, they give us the supreme pleasure of thinking that "I should have got that myself."

Agatha Christie is not a great writer, and her 66 novels vary widely in quality. But the best of her books are well worth revisiting. There is a clarity about them and a shrewd understanding of the vagaries of human nature. Christie was no fool. She's also a better writer than her reputation might lead you to expect.

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926), for example, if by any chance you don't know the twist, still has the power to take your breath away. And, if you do, you can admire how it's done. Murder at the Vicarage (1930) has elements of social comedy. A Murder is Announced (1950) tells us a great deal about the stresses of post-war British society. Crooked House (1949), one of Christie's own favourites, breaks an unspoken taboo of the genre that many readers still find shocking.

We will never know the precise secret of Agatha Christie's extraordinary success. But the simplest, though not the only, reason for it is this: she understood the power of story and how to exercise it on her readers.

In her recent book, Talking About Detective Fiction, PD James quotes Robert Graves's judgement: "Agatha's best work is, like PG Wodehouse and Noël Coward's best work, the most characteristic pleasure writing of this epoch and will appear one day in all decent literary histories. As writing it is not distinguished, but as story it is superb." The next best thing to a howdunnit?

Andrew Taylor's new novel, 'The Anatomy of Ghosts' (Michael Joseph), will be published on 2 September. Today at 5pm he will be taking part in an event to celebrate '120 years of Agatha Christie' at the Theakstons Old Peculier Crime Writing Festival in Harrogate. Booking: 0845 130 8840

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments