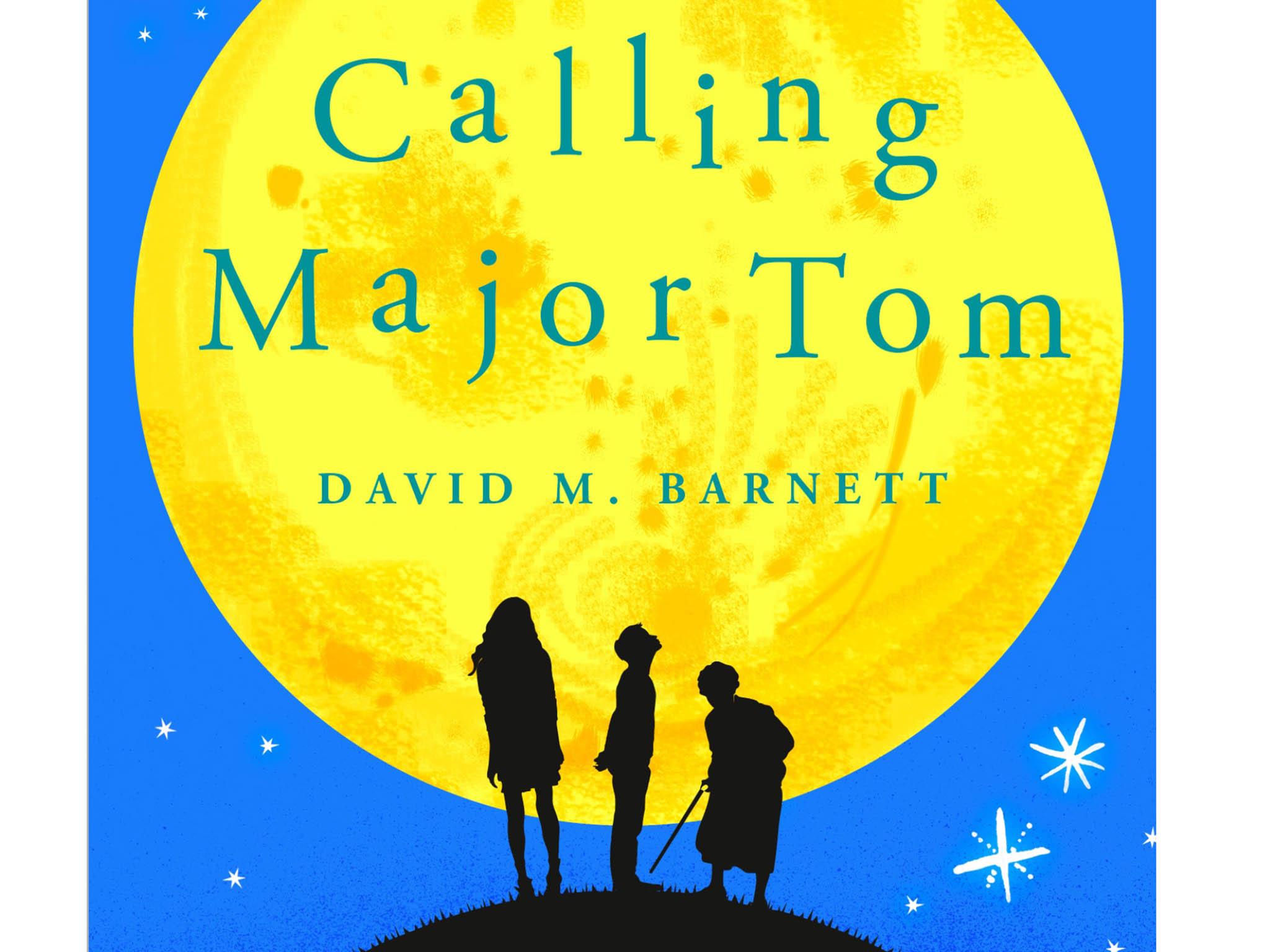

Major Tom meets Coronation Street: An out of space encounter with a family from Wigan

A year ago today, David Bowie died. One week later, David Barnett started writing ‘Calling Major Tom’. Like many people, Barnett could not escape the influence had on his life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Not very long into last year I sat down at my laptop and wrote these words: “The day Thomas turns 46 begins with the news that David Bowie has died. Well, that’s just great, thinks Thomas. And on my birthday as well.”

It’s fiction, the opening lines to chapter six of my novel Calling Major Tom. But it’s also not fiction as well, because the day I turned 46 began with the news that David Bowie had died. That day was 11 January 2016. Bowie had died the day before, but the news filtered through to most of us the next morning.

At that point, I wasn’t writing a book titled Calling Major Tom. The novel wasn’t even a twinkle in my eye. But just a little over a week later I would indeed be writing that book.

Calling Major Tom isn’t about David Bowie, but he quietly haunts it. Before he died, I probably hadn’t thought about him too much, not until the release of Blackstar, his final studio album, released on his 69th birthday, two days before he would die.

I was pleased that Bowie had released a new album. He was one of those figures who were always part of the landscape of my life, even if I didn’t obsessively collect his records, even if I never saw him play live. “Space Oddity” was released six months to the day before I was born, and I feel I must have absorbed it by osmosis even while in the womb. It is one of those songs you just know, intuitively, completely. I can remember the irradiated Day-Glo video for “Ashes to Ashes” giving me post-apocalyptic nightmares, being deliciously disturbed by the sleeve to Diamond Dogs. A girl who lived in our street wrote “SHAZ LUVS BOWIE” on every schoolbag she ever owned, as long as I knew her.

What Calling Major Tom is about is Thomas Major, a grumpy, curmudgeonly man who happens to share a birthday with me. Thomas, by dint of a series of admittedly audacious happenings and coincidences (with which I hope the reader will stash their disbelief in the overhead locker and allow themselves to be carried along), ends up being the first human being to go on a manned flight to Mars. We meet him just a day or two after the launch, enjoying the isolation and the feeling that he’s left Earth behind forever.

Through flashbacks we see that Thomas Major has not had a very good life, and has been dogged by tragedy – some of it unavoidable, some of his own making – that has led him to the point where he’s quite happy to settle into the role of grouchy misanthrope with only one real love: music. But then he dials a wrong number from space, his signal bouncing off a satellite network around the Earth and accidentally putting him into direct contact with the rather dysfunctional Ormerod family in Wigan.

The Ormerods are Gladys, who's surfing the edges of dementia, and her grandchildren, intelligent but bullied James, 10, and Ellie, who at 15 is trying to hold the family together while their father is in prison. What follows is a dialogue between Thomas and the Ormerods, and the prospect that Thomas, though farther away from the Ormerods than any other person on Earth, might be the only person who can help them. And Thomas discovers that other people might not actually be the hell that he’s let himself believe they are.

The previous year for me had been one of upheaval. In the middle of 2015 I was made redundant from the local newspaper where I’d worked for 14 years, marking the end of 26 years of continuous employment, again almost to the day, with the regional press, a career I’d begun when I was 19.

With support from my family I embarked on a career as a freelance journalist, something I’d always wanted to do but never had the courage to until I was pushed, and over the following six months made something of a success of it, working for most of the UK nationals in some form or other.

I’d also taken on some part-time lecturing work imparting my knowledge to the journalists of the future (the irony wasn’t lost on me), and it was while at one of these sessions, on 19 January 2016, a little over a week after Bowie had died, that Sam Eades from Orion contacted me via my agent, John Jarrold.

It was a weird time: my freelance career was burgeoning, I was enjoying the lecturing, and I was glad to be out of an industry that was on its backside; the flip side of that was I always loved working in local papers but was just frustrated by the swingeing cuts (which is a phrase you’ll only ever find in local papers) which came along with increasing frequency. I was disappointed that a Victorian fantasy trilogy I’d written hadn't done better, and worried this might signal the end of my fiction-writing career. More pressingly, my dad was just about beginning several stretches in hospital with a battery of illnesses that would eventually end very badly.

A conversation ensued with Sam Eades at Orion. She was part of a team setting up a new commercial fiction imprint, Trapeze. She’d enjoyed some of the work I’d done as a freelance journalist, and thought I might be a good fit for the imprint. It was the sort of call any writer dreams about. We started talking ideas and both remembered that just before Christmas Tim Peake, the British astronaut on the International Space Station, had made a wrong-number call to a retired teacher. Imagine, we both said, if that had ended up in an ongoing dialogue between a spaceman and a pensioner.

“Like Major Tom,” one of us said. “Crossed with Coronation Street,” added the other. I can’t remember now which was which, in the white heat of a creative phone call where ideas were tumbling around like rogue satellites. But, eight days after my 46th birthday, a little more than a week after David Bowie died, the plot of Calling Major Tom was suddenly laid out before me, just minutes after the concept had been born.

David Bowie died a year ago today. I was born 47 years ago tomorrow. And on 19 January, a year to the day that the idea was formed, Calling Major Tom gets its ebook publication, ahead of paperback release on 29 June.

It’s not really a book about space in the same way that it’s not really a book about David Bowie. It’s a book about love and friendship, loneliness and sadness, and realising that life is not always what we think it is. I thought about dedicating the book in some way to Bowie, but there was no need; I didn’t know him, after all, and the book is shot through with him anyway, like a song heard on someone else’s radio, or a peeling bill-poster half-seen through a bus-window. In the end I dedicated it to my wife and children, and when the book comes out it will be in memory of my dad.

I’d finished it before he died at the end of September, but he’ll never read it. To be honest, it isn’t really his thing anyway. But while writing Calling Major Tom, I did realise that no matter how bad things seem or actually are, there is always hope. And we can find out – sometimes in the most remarkable and unexpected ways – that even if like Thomas we give up on the world, sometimes the world doesn’t give up on us.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments