A most unique year: Judging the Booker Prize in the middle of a pandemic

Unable to read physical copies of many of the novels and faced with homeschooling and coronavirus, judging the Booker Prize this year has been wholly different to normal, writes Alex Marshall

Emily Wilson, a classicist, translator and single mother in Philadelphia, has spent much of lockdown homeschooling her three children and caring for a puppy. On top of that, as one of this year’s Booker Prize judges, she had to read more than 100 books.

She often woke before dawn to keep up the pace, which at times meant finishing a book a day. But she says the task was a “great gift” during this challenging year. Whenever she thought about turning on the news to check coronavirus death rates, she could tell herself: “No, I can’t do that. I’ve got 300 pages of a great novel to read.”

For that escape, Wilson says: “I was very lucky.”

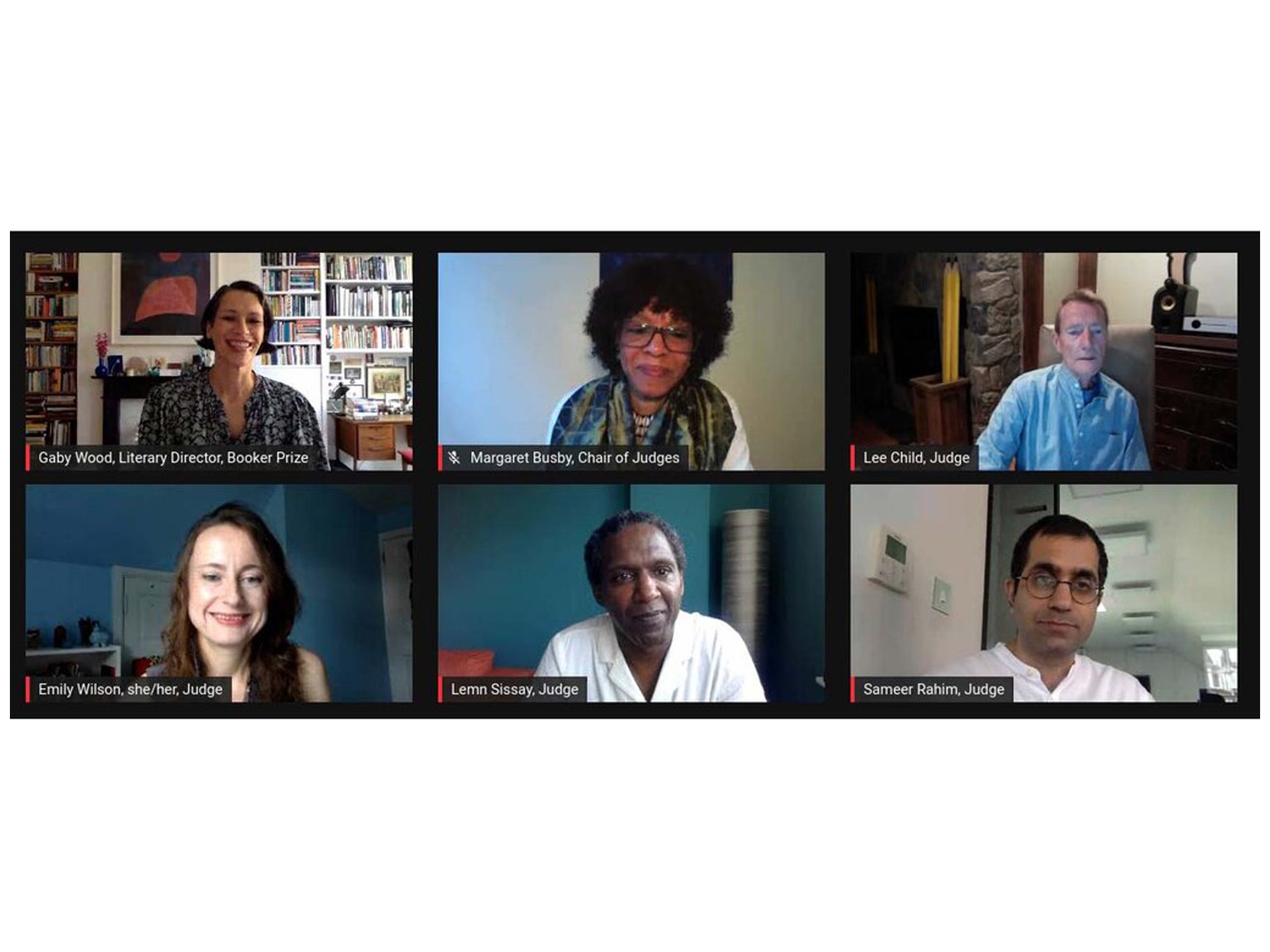

Among the countless projects, events and routines that the pandemic has upended, the Booker Prize, one of the world’s most prestigious literary awards, has also had a year like no other. The five judges, who typically gather in London several times before announcing the winner, instead met over Zoom, and they completed their reading assignments in wildly divergent circumstances.

The British author and critic Sameer Rahim read book after book with his newborn baby asleep in the crook of his arm. Lee Child, the bestselling thriller writer, has been at his Wyoming ranch, surrounded by acres of emptiness. Poet Lemn Sissay has been in a London apartment.

Margaret Busby, a publisher and the chair of the judges, tried to balance the work while coping with the death of her sister from cancer. “How did I keep going?” Busby asks. “She wouldn’t have wanted me to give up.”

The judges announced the six contenders for the Booker Prize on Tuesday, passing over literary heavyweights like Hilary Mantel and Anne Tyler, who made the prize’s longlist in July, in favor of debut novelists including Brandon Taylor and Douglas Stuart.

The judging process began in December, long before the pandemic had taken hold. Each month, the judges received a stack of books, then met in London or online to work out which ones they thought should make it to the next round.

In March, they started talking about holding a meeting at Child’s New York apartment. “Then, obviously, things changed quite quickly,” Rahim says.

Almost overnight, as Britain and the United States went into lockdown, the judges stopped receiving physical copies of books, as publishers were unable to get anyone to send them out, Busby says. Instead, the monthly haul arrived as PDFs. (Judges ultimately received 162 submissions.)

We’d all be mid-war, some Cromwellian fight over a book, and suddenly Sameer’s baby’s lovely head would pop up and we’d all just melt

“That was the negative for me,” Child says about the PDFs. “I so much prefer an actual book.” He ended up reading them “lying on my sofa, staring at my laptop for six, eight, 10 hours at a time”.

Sissay says lockdown, for all its problems, benefited the judges, since all their other plans were cancelled, from book tours to broadcast jobs. “There was nothing to do but read,” he says. “There will never, ever, be a judging panel that has so much time to just focus on the books.”

Initially, the reading pile overwhelmed him more than the pandemic. “There was a point when I was like, ‘I can’t do this any more’,” he says. “It was just shock and overload.” But Sissay taught himself to read quickly – he won’t reveal his method – and soon appreciated the distraction the books gave him.

None of the judges say the pandemic influenced the types of books they favoured. “If I hadn’t been judging this, I’d probably have been reading murder stories,” Wilson says. “I’d have wanted some darkness where it was all wrapped up – some sense of closure. But with this, I just enjoyed being taken to a different world every day, even if it had some darkness in it.”

Rahim agrees. “At a time when you couldn’t really see anyone, what I found great was being able to take a book every evening and get to know someone,” he says. “It was like a blind date: sometimes great, sometimes not so great, sometimes indifferent. It was replacement socialising.”

The judges’ monthly meetings continued on Zoom. Busby says she liked the glimpses into the other judges’ lives that came with it. “You can see who smokes,” she says with a laugh.

But she missed being in a room together, she says. “You can’t turn to someone and say, ‘What do you think?’”

The other judges felt there were some advantages. For Child, Zoom was a more intimate environment, making it easier to say when he disagreed with another judge. Rahim thought there were fewer arguments because it’s harder for people to speak over each other. Even if things did get tense, the medium meant there were easy ways to improve the mood.

“We’d all be mid-war, some Cromwellian fight over a book, and suddenly Sameer’s baby’s lovely head would pop up and we’d all just melt,” Sissay says. Wilson’s puppy – a poodle mix called Pepper – would make occasional appearances to similar effect.

The judging has not ended. The winning book, whose author will receive a prize of £50,000, is scheduled to be unveiled on 17 November at a ceremony in London. The judges will reread the entire shortlist before coming to a decision.

Whatever they choose, the impact of this process looks set to stay. Sissay says five weeks ago he used his newly acquired speed-reading skills to read Allen Carr’s Easy Way to Stop Smoking in three hours, in the hope of tackling his 40-a-day habit. He hasn’t smoked since.

Wilson has enjoyed the experience so far. “If you’re going to be living through a pandemic, then reading a lot of fiction is a good thing to do,” she says.

“Actually,” she adds, “it’s a good thing to do while trying to live through anything.”

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments