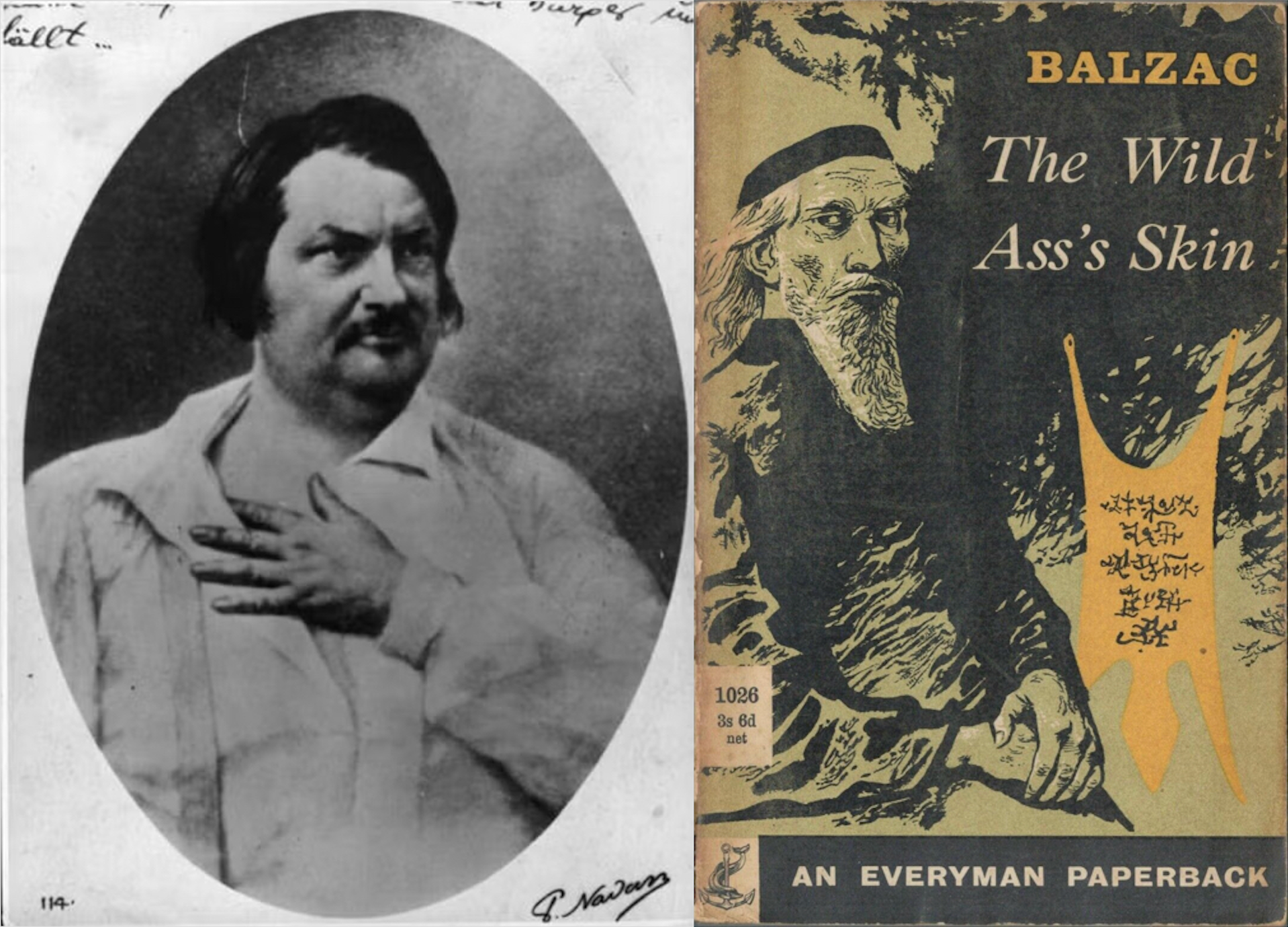

Book of a Lifetime: The Wild Ass’s Skin by Honoré de Balzac

From The Independent archive: Marina Warner wraps herself in the French novelist’s Faustian fairytale that shows the true costs of possessing – and being possessed by – great wealth and power

Bent on killing himself by throwing himself into the Seine after losing his shirt at the gaming tables, Raphael de Valentin, the romanticised, doomed young hero of Balzac’s early 1831 novel, La Peau de chagrin (translated as The Magic Skin or The Wild Ass’s Skin), turns into an antiques shop to while away the hours till darkness (when he can be sure not to be rescued). There he finds himself in an emporium of civilisation’s treasures, from all over the world and in every marvellous material, executed to the highest degree of human art.

Eventually, the eerie, wizened keeper appears and shows Valentin the magic skin which gives the novel its title. It’s the hide of a wild ass and, like the ring of the Nibelungen, has the power to grant its owner every wish. But in return it will take possession of Valentin, body and soul. Every time it performs, it will shrink – and Valentin’s life will shorten in accord.

The pun in Balzac’s title can’t be captured in translation: shagreen in English – green shark’s skin – isn’t freighted like French chagrin, sorrow. The scene of the fatal bargain is pure phantasmagoria: among the gleaming heaps of stuff, the decrepit antiquarian lifts his lamp so that Valentin can read the inscription on the skin. It’s in Arabic, a promise and a warning. Valentin enthusiastically accepts the fatal Faustian pact.

The famous chronicler of French society and of human folly and vice had his first, huge success with this book, which bows to the tradition of fairytale. In the footsteps of Voltaire, Balzac chose the Asian mode to project his “philosophical tale”, his scabrous allegory of contemporary corruption. The hideous “talisman” represents the first fully dramatised French use of a word which entered Europe from the Middle East, chiefly through stories of The Arabian Nights. But the slaves of the lamp and the ring don’t destroy their masters, whereas Balzac’s indictment of money, desire, and modern consumption furiously metes out punishment.

In the lurid denouement, Valentin has been reduced to a state of vegetable torpor and decay, while the skin has shrivelled to the size of “a periwinkle leaf”, when he’s visited by his love, Pauline.

In a lavish Liebestod, they’re reunited. But this fulfillment comes at a supreme cost: she, realising her deadly effect, tries to strangle herself with her shawl, while Valentin sinks his teeth in her breast and expires. The driven ghastliness – and the phallic symbolism – of their final moments provokes “horrid laughter”.

But it must be admitted that the frenzy and the plenitude of Balzac’s weird, Asian fantasy astonished me all over again. At a time when millions of hard-working people are having to use food banks while publicly listed company directors are taking home more money than ever, Balzac’s fable about the gods of excess and greed lacerates the soul.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments