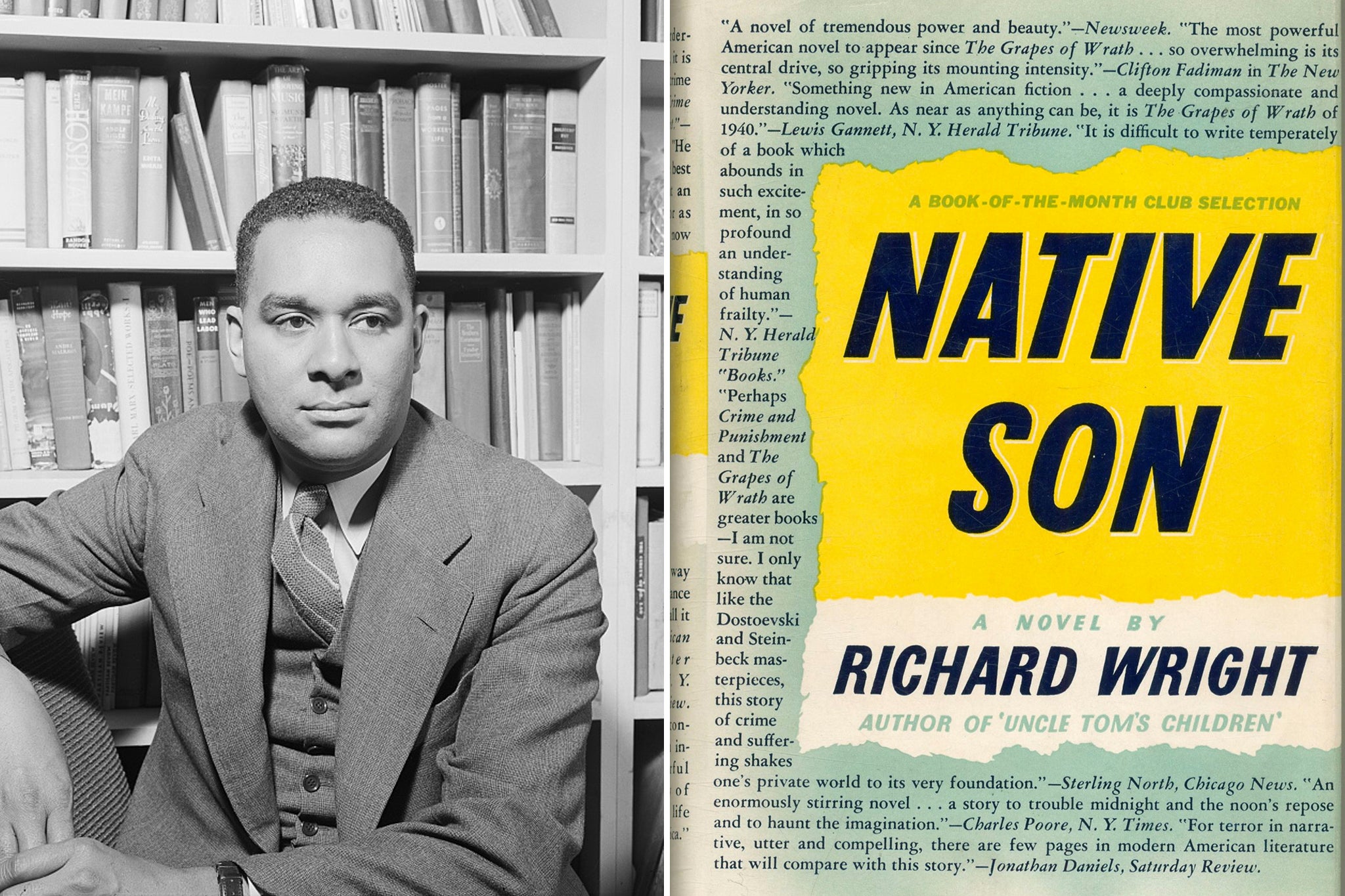

Book of a lifetime: Native Son by Richard Wright

From The Independent archive: Caryl Phillips on the American author’s first novel that made him the wealthiest Black writer of his time

The American author Richard Wright is most famous for this one book. It was his first novel, and on its publication in 1940, it became one of the fastest-selling novels in American literary history: a remarkable feat for a 32-year-old, largely self-educated man from Mississippi. It would be fair to say that it changed his life forever. He went on to write many other books, both fiction and non-fiction, but at the time of his death, at the young age of 52 in 1960, many of the obituary notices referenced Wright as the author of just this one book, Native Son.

The novel tells a stark, and somewhat violent, story of a young black man who becomes hardened, and desensitised, by his upbringing in inner-city Chicago. He is an intelligent fellow, but unlike both his sister and his mother, he is not inclined to accept religion into his life as a way of surviving the misery of his existence, nor is he prepared to do as many other men seem to do and reach for the bottle. He takes a respectable job in the house of a wealthy family, but becomes involved in the death of a young woman and finds himself hunted by bigoted officials whom he correctly assumes will neither listen to his version of what happened nor see him as anything other than a brute.

It is one of the great books about inner-city anxiety, and recognisable to a great many individuals who grow up feeling disempowered and disenchanted

Eventually, he is captured and tried. He faces his death sentence with dignity and achieves an insight into his situation that raises him, and his story, to a truly tragic pitch. In a heartbreaking conclusion to the novel, he understands that his life has been squandered. He also comes to accept the fact that there are many more like him, and the system will continue to produce young men who will never reach their full potential because society simply refuses to see them as being anything other than a disposable burden.

Native Son is not the best novel that I have read; far from it. At times the novel is melodramatic, and at other moments its polemical tone is in danger of bringing down the whole fictional construct. It shouts, and occasionally it preaches. It is, however, one of the great books about inner-city anxiety, and recognisable to a great many individuals who grow up feeling disempowered and disenchanted, and convinced that they can therefore behave in whatever manner they choose to because society doesn’t actually give a damn about them. On both sides of the Atlantic there are many young men who, were they to pick up this book, might find – as I did when I first read it as a 20-year-old – that the beginning of freedom is rejecting, not absorbing, other people’s reductive gaze. Sadly, for Wright’s hero, this life lesson is visited upon him too late.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments